A Mystery Hidden in Plain Sight (Part Four)

The fourth part of a four part essay

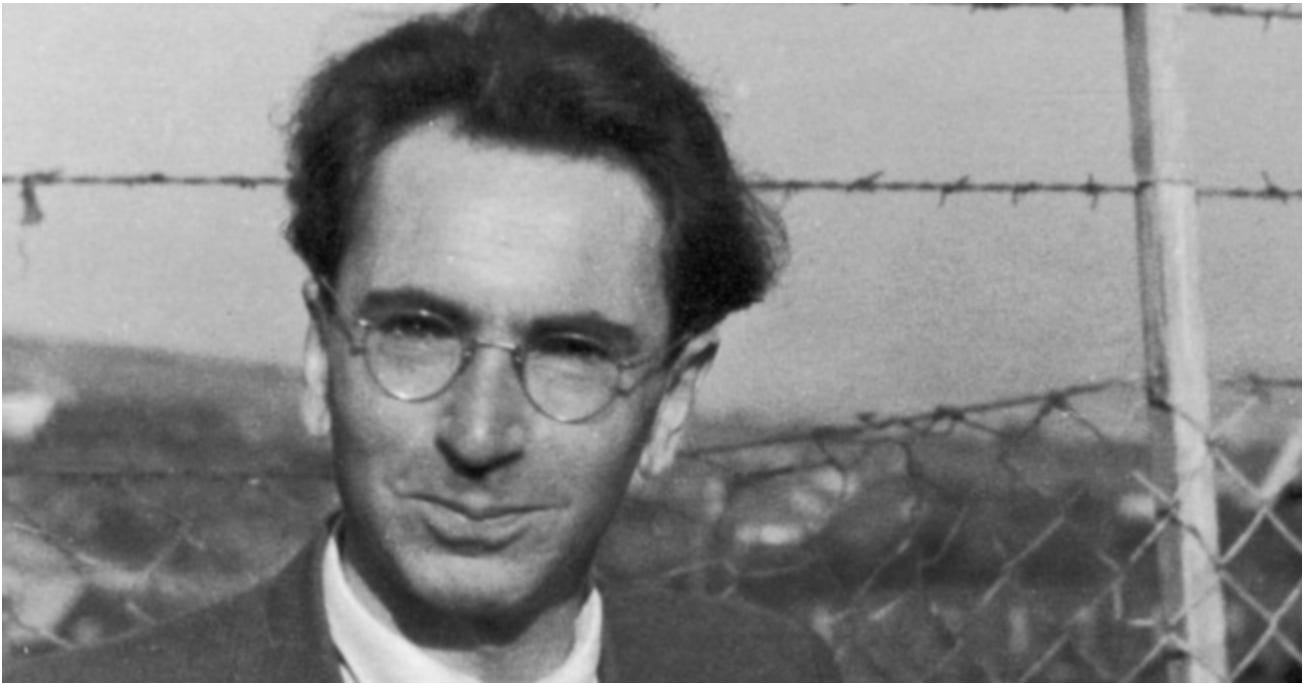

1. Viktor Frankl

Photo 3800952 / Barbed Wire © Jokerproproduction | Dreamstime.com

Why did a willingness to suffer open the door to greatness for Mike, David and Roy, whom we discussed here, here and here?

I’ve never heard Mike or David discuss suffering explicitly, and to my knowledge Roy didn’t comment on it, either. But Viktor Frankl did. Viktor was a Viennese doctor and psychiatrist when he was incarcerated in Auschwitz. He was almost sent to the gas chamber when he arrived, and although he survived that day, along with every other prisoner he was completely stripped, his head was shaved, he was tattooed, and forced to wear the rags of a dead prisoner. Most importantly for Viktor, the book manuscript he had just completed was taken from him, and he never saw it again.

Viktor’s motivation to survive was to re-write the lost manuscript, which at the time represented his life’s work. Viktor retained his will to live for years during his terrible ordeal: slowly starving, forced to wear filthy, vermin-infested, threadbare rags in the middle of a Polish winter, wearing shoes with no laces and almost no soles, Viktor and his fellow inmates were marched out at dawn to dig ditches in the frozen mud with tools he was almost too weak to hold, much less use.

Part of Viktor’s strength, like Mike, David and Roy, came from a powerful sense of personal identity unaffected by being badly treated by others. Viktor found his past gave his identity an unshakeable foundation of confidence and self-worth despite the misery and suffering of Auschwitz:

“Suddenly I saw myself standing on the platform of a well-lit, warm and pleasant lecture room. In front of me sat an attentive audience on comfortable upholstered seats. I was giving a lecture on the psychology of the concentration camp! . . . . By this method I succeeded somehow in rising above the situation, above the sufferings of the moment, and I observed them as if they were already of the past. Both I and my troubles became the object of an interesting psycho-scientific study undertaken by myself.”

Source: The Viktor E. Frankl Institute of America

In Man’s Search for Meaning, the book he wrote after surviving Auschwitz, Viktor explains everything can be taken from us: our profession, our possessions, our income, our status, our dignity, our clothes, our access to enough food to avoid starvation, and we can be beaten, starved, frozen, neglected when we are ill, and forced to work under almost impossible conditions—but we have one freedom left.

The freedom that remains to each of us is the choice of how to respond to suffering.

As Viktor wrote:

“The experiences of camp life show that man does have a choice of action . . . . Man can preserve a vestige of spiritual freedom, of independence of mind, even in such terrible conditions . . . We who lived in concentration camps can remember the men who walked through the huts comforting others, giving away their last piece of bread. They may have been few in number, but they offer sufficient proof that everything can be taken from a man but one thing: the last of the human freedoms—to choose one’s attitude in any given set of circumstances, to choose one’s own way.”

Research tells us that the foundation for motivation is a belief we can make a difference in our lives, and we have control over what happens to us. Viktor describes three ways we can find meaning in our lives: (1) by expressing our creativity through our work; (2) by doing our duty and fulfilling our obligations towards others; and (3) by our attitude in response to unavoidable suffering.”

The third way doesn’t require us to choose suffering, but it does requires us to accept suffering we can’t avoid. A person who accepts suffering because there is no other way to achieve their goal, like Mike did, opens the door to greatness. Do you know what Roy took with him on that desperate helicopter flight into battle? A medical kit and a knife. His goal was to tend the wounds of his beleaguered team and stabilize them long enough to be rescued. He wasn’t going in to exact revenge on a thousand enemy soldiers. He accepted the wounds he received as he ran through the jungle towards his men because it was the cost of saving them. He fought the enemy because that’s what it took to get his men out. That’s why Roy succeeded in saving seven of the twelve men against overwhelming odds, despite being wounded himself thirty seven times.

In Auschwitz, Viktor learned the truth of what Dostoyevsky wrote when he was a political prisoner in Siberia, “The only thing I dread is not to be worthy of my sufferings”. Viktor comments from his own experiences as both a starving inmate in Auschwitz and as a wealthy and world-famous psychiatrist and author, “Everywhere man is confronted with fate, with the chance of achieving something through his own suffering.”

Holding our hand over a flame makes us suffer, but it probably isn’t unavoidable suffering. By contrast, running into a burning house to save a child, even if we suffer burns, doesn’t result in pointless pain. We have accepted a refiner’s fire that transforms us into the best version of ourselves. When we accept suffering we are forging meaning.

Of course, we may choose to respond to suffering by deciding the universe is indifferent to us, or that the essence of reality is fundamentally cruel or just absurd. But we do have that choice. We can also decide to become our best selves and create meaning with our lives.

Revealed: The Mystery Hiding in Plain Sight

All of us are aware suffering is inescapable in life, and we also understand the connection between suffering and the meaning of life. We may not like it, but we know it’s true. We know it because we have mothers.

ID 41825900 © Rafael Ben Ari | Dreamstime.com

Since the beginning of the human race, billions of women have given birth in pain and suffering. Suffering is the ineluctable path to bringing new life into this world. Twice in his short book, Viktor quotes Nietzsche’s comment “A man who knows the Why can bear any How”.

It’s women who have proven this by facing fear, pain and often the risk of death to give birth to their children.

The Latin word “laborare” originally meant not just “work”, but hard work, endurance, and suffering. Giving birth is the quintessence of “labor”, an inescapable, vital task that must be performed despite its difficulty and severity, despite the agony to be endured in accomplishing the task. Every mother who has given birth knows this.

The classical Greeks aspired to express personal excellence during the most severe trials, for example, the original Olympics or their ultra-violent battles. The epitaph on the tombstone of the great playwright Aeschylus, who invented tragedy, doesn’t even mention his artistic achievements. It commemorates his service as a hoplite, fighting shoulder to shoulder, shield to shield, spear pointing towards the enemy, in the great national victory of Marathon:

Here lies Aeschylus, son of Euphorion

In the wheat-bearing fields of Gela;

The plain of Marathon witnessed his courage,

And the long-haired Persian knows it well.

The Greeks understood the highest arete is expressed under the most frightening and painful circumstances. For that reason, the Greeks honored women’s courage by considering childbirth a woman’s battlefield.

Roy deservedly won the Medal of Honor for the courage he displayed fighting for hours to save seven men, but six hours isn’t even a long time for a woman in labour, especially when she’s giving birth to her first child.

How many women, after hours of labor, convinced they have already given everything they have to give, utterly exhausted, worn down by pain, have asked whether their baby is finally about to be born? Only to be told they are only seven centimeters dilated, with hours of labor still ahead. Somehow, billions of women have found unknown reserves within themselves they never imagined they had, and were able to persevere and bring their baby into the light.

Photo 75509093 © Innaastakhova | Dreamstime.com

Even though our response to suffering is an intensely personal choice, and often a completely private struggle, Viktor tells us the transformation that begins within us does not remain limited to ourselves. It is women, not men, who are the most pure proof of what Viktor writes:

“I wish to stress that the true meaning of life is . . . in the world rather than within man or his own psyche . . . . being human always points, and is directed, to something, or someone, other than oneself . . . . The more one forgets himself—by giving himself to a cause to serve or another person to love—the more human he is.”

It is also women who have demonstrated, millions of years before the research on brain plasticity, that our bodies can be transformed to support the human will: various hormonal changes soften the cartilage at the front of a woman’s pelvic bone, allowing it to loosen and open enough to admit her baby's head—only one of many changes. During labor a woman’s body and neurological system are coursing with the potent hormones of oxytocin and endorphins. Despite her suffering and pain, a mother is effectively a superwoman during childbirth.

It’s the great mystery each of us already knows.

In many ways, motherhood is such a severe test, one that lasts years and decades after the dramatic moment of giving birth, that a heroic understanding of motherhood makes sense, even when, and perhaps especially because, a woman has to die to her original self-conception as a woman in order to achieve the complete transformation into the mother whom each of us loves so deeply, and with such gratitude.

Photo 96354061 © BÅÅyjak | Dreamstime.com

Even when suffering is constituted by daily drudgery and the relinquishment of previously cherished ambitions, its acceptance can transform us into our best selves.

Viktor wisely observed, “Ultimately, man should not ask what the meaning of his life is, but rather he must recognize that it is he who is asked . . . each man is questioned by life.”

Mike, David, Roy and Viktor are exceptionally unusual men, and each found his uniquely personal answer to the question he was asked by life.

DNA studies tell us that throughout human history, 80% of all women who have ever lived became mothers. They were questioned by life when they became aware they were pregnant, and billions of women said Yes to life, knowing the consequences. Since the beginning of time, our mothers have lived the intimate connection between suffering and meaning.

The extraordinary is normal. The path from suffering to greatness is a miracle happening thousands of times every day. Our brains and bodies can be thought of as a lamp without electricity. If we respond with a Yes to the question life asks us, and if we persevere despite the suffering, we become incandescent—lights illuminating the darkness.

2. “Et in terra pax hominibus bonae voluntatis (And peace on earth to all people of good will).”

Mass in B Minor, Johann Sebastian Bach

Johann Sebastian Bach composed this piece to celebrate the end of the occupation of Weimar by the troops of Frederick the Second of Prussia. I refuse to call the famous King of Prussia, an embittered misanthrope and great slaughterer of men, Frederick “the Great”.

It is Bach who was great. Indeed, arguably he is one of those people of whom “the world is not worthy”. Years ago, a well-meaning friend told me about a media program she had enjoyed which mocked Bach by reading some of the servile letters Bach was forced to write the petty German princes and dukes who ruled the jurisdictions in which Bach lived. These pompous nobodies, all but forgotten by history, forced Bach to beg for the smallest increases in salary or the most minor improvements in his family’s living conditions. Yet under those conditions, Bach was able to write this consoling and inspiring piece proclaiming peace on earth to all people of good will.

The B Minor Mass, of which “Et in Terra Pax” is a small part, is far too lengthy a masterpiece to be performed in either a Roman Catholic or a Protestant church service. It transcends mere religion and expands into Bach’s pristine universal expression of spiritual homage to the glory of God.

Bagels in Central Park

I just returned from a wonderful 24 hours in New York City with my daughter Xanthe. We started out in her meticulous, tastefully decorated apartment in Williamsburg and then caught the subway to the Upper East Side, where we went to the exquisite Neue Galerie.

We both love Vienna, and there’s no better place to experience breathtaking Austrian art and authentic Viennese café atmosphere and cuisine, than the Neue Galerie. Because yesterday was a public holiday, the Neue Galerie’s Sabarsky Café had interminable lines, so we walked to Madison Avenue, organized some delicious bagels, and walked back across Fifth Avenue and found an empty bench in Central Park.

We enjoyed lunch in the spring-like weather while speculating which of the passing runners and cyclists were acting on their New Year’s Resolutions.

I read your series with great interest, Chris. You certainly highlight what our amazing brains can accomplish if focused to do so. But, you also focus on the positive attributes that are more associated with masculinity (except for your mother/birth suffering portion, of course) - to wit: courage, duty, strength, self-reliance, risk-taking. These men you focused on are all heroic, and should rightly be celebrated. I am not saying that you couldn't find a story like these about some heroic woman; I am saying - there won't be nearly as many!

When I read "Into Thin Air", I was struck by the story of Buck Weathers who saved himself while others would/could not. I also read the book Deep Survival: Who Lives, Who Dies and Why. It's the story, almost always of men, who face great suffering and risk and make it out alive. Or look at the amazing story of Tham Luang cave rescue - a whole bunch of guys risked their lives (one lost his) to save the kids trapped there. And so forth. Why am I writing this? Because many men are awesome in a way I - and most women - are not. And it's not celebrated enough in our culture.

Feminists are often accused of trashing men. I just want to say that I am a from-a-very-young-age feminist, and I what to be the counter-tide of feminists who appreciate our differences and our different strengths as well as our many shared human traits.

Vive les hommes!

Another awesome piece, Chris. I periodically re-read Viktor Frankl's Man's Search for Meaning as I think it's like medicine for the soul. "When we accept suffering we are forging meaning" -- beautifully put. I loved your words on Bach and totally agree on your refusal to call Frederick the Second of Prussia, "The Great". Thank you for writing so profoundly. I really enjoy reading you. (PS: great photo with your daughter!)