Purgatory and the cost of believing “the theology”

In Part One we discussed how St. John of the Cross’s mentor Teresa of Avila, or Teresa de Jesus as she was known during her lifetime, provides one of the best examples of how we can evolve spiritually by transforming our erotic energy.

In this Part Two we will consider how Teresa de Jesus almost killed herself by blindly believing the dominant ideas of her age.

When explaining why she became a nun, Teresa admitted frankly that her decision to take vows was motivated purely by fear:

I saw that the religious state was the best and the safest. And thus, by little and little, I resolved to force myself into it. The struggle lasted three months. I used to press this reason against myself: The trials and sufferings of living as a nun cannot be greater than those of purgatory, and I have well deserved to be in hell. It is not much to spend the rest of my life as if I were in purgatory, and then go straight to Heaven--which was what I desired. I was more influenced by servile fear, I think, than by love, to enter religion. (Chapter 3, Page 76)

The future saint was born in 1515 as Teresa de Cepeda Dávila y Ahumada. She was the beloved youngest daughter of the wealthiest man in the ancient Castilian town of Avila. As a girl, Teresa was described as moving with grace and laughing often, with dark eyes, pale skin, full lips and chestnut hair. She had a warm, passionate, charismatic personality.

She was taught the culture of Roman Catholic Spain in the early 16th century, and assimilated it deeply. At the age of seven, Teresa and her eleven year old brother Rodrigo decided to slip out of their palace home, through the gates of the walled city of Avila, and travel to Moorish Africa.

Their objective? To willingly be captured and martyred by beheading.

Teresa and Rodrigo were highly intelligent children. Their culture had taught them that a martyr’s death was the way to enjoy eternity in paradise.

It seems toxic and irrational to us. It was certainly toxic, but given the assumptions of their culture Teresa and Rodrigo were being perfectly rational. In any case, one of their uncles spotted them on the road from Avila and brought them safely home.

Teresa survived her early expedition to martyrdom and grew into a vivacious, attractive, eloquent teenager. She enjoyed meeting people and loved the considerable attention she received as one of the most marriageable young ladies in Avila. She was a good dancer, an excellent horsewoman, and an avid reader, especially of the late medieval romances of chivalry derided in Don Quixote (and beloved of Don Quixote himself).

Teresa de Cepeda Dávila y Ahumada as a teenager. Original art generated by the author via Midjourney

Teresa seemed destined for a glamorous dynastic marriage with a wealthy aristocrat. But something happened in Teresa’s private life when she was sixteen that lasted three months and radically changed her life by triggering the existential terror she describes in the passage quoted above.

It involved one of her female cousins, and the experience generated in Teresa an indelible sense of her own profound wickedness. Teresa was an exceptionally clear writer, but she only offered dark hints about the nature of her wicked acts. One of her few non-Roman Catholic biographers, Vita Sackville-West, herself a sophisticated aristocrat and bisexual, convincingly speculates the mysterious episode involved “the rudimentary experimental dabblings of adolescent girls.”

The culture of her age assured Teresa she faced centuries in Purgatory—if not an eternity in Hell. Two of the greatest artistic geniuses of Europe, Dante Alighieri and Hieronymus Bosch, had produced deeply compelling descriptions of Purgatory, upon which Roman Catholic theologians had built a grand, terrifying conceptual kingdom of the suffering dead.

Teenage Teresa de Cepeda Dávila y Ahumada in a Boschean Purgatory. Original art by author generated via Midjourney

The politics, economy, society and culture of medieval Europe were shaped by the assumption that it was better to suffer during one’s life time in exchange for not suffering for the equivalent of multiple lifetimes in Purgatory, or for eternity in Hell.

Belief in Purgatory was the foundation for the dominant institutions of Teresa’s world. The Roman Catholic Church collected huge sums of money for “indulgences” that promised to shorten the time one’s deceased loved ones were being tormented in Purgatory. Churches, monasteries and convents were largely funded by wealthy believers wishing to have masses and other prayers said on behalf of their own souls after they had died and were presumably suffering in Purgatory. Purgatory was also a terrific recruiting tool for military campaigns: when a Pope declared a Crusade, the declaration included a blanket indulgence exempting any soldier who died during the Crusade from Purgatory and dispatching him directly to Heaven, just as Teresa and Rodrigo had hoped to do as children.

I’m reminded of the comment by the great 20th century economist John Maynard Keynes on a different subject: “this . . . is an extraordinary example of how, starting with a mistake, a remorseless logician can end up in bedlam."

Assumptions and Consequences

Every age is shaped by deep assumptions shared by most people and treated as evidence-based. We may be appalled by the idea that young children would seek to be beheaded, but research by the NYU scientist Jonathan Haidt makes it clear that our culture today is inculcating young people with technologies or ideas that are having an unprecedentedly negative influence on their well-being. These two graphs below will suffice for an abundance of other corroborating research:

Whatever is causing widespread psychological stress in young people today, our commitment to believing the science and making data-driven, evidence-based decisions is not protecting our children and teenagers from misery. Perhaps this trend is a sign we should be examining the deepest assumptions of our own age for the equivalent of the 16th century Spanish Catholic belief in Purgatory.

The toxic influence of mistaken assumptions also caused the adolescent Teresa almost unbearable psychological pain. She found herself inside a 16th century Spanish matrix from which there seemed to be no escape. After 1492 the seemingly empirical worldly credibility of the Roman Catholic Church, which taught the existence of Purgatory, was at an all-time high:

In 1492, after eight hundred years of military campaigning, the “Catholic Monarchs” Ferdinand and Isabella defeated the last of the Moorish kingdoms, completing the Reconquista (Reconquest") of Spain;

In 1492, the “Catholic Monarchs” expelled the last of the Jews from Spain who had refused to convert to Catholicism;

In 1492, Columbus discovered the New World with a small fleet funded by the Catholic Monarchs, and

By the time Teresa was undergoing spiritual crisis, it was clear that the enormous amounts of gold and silver beginning to flow from Spain’s New World possessions would turn the country into a superpower.

For Spanish Roman Catholics it seemed obvious that God was rewarding them with almost unimaginable wealth and power. Spain would act on this assumption and devote its Golden Century to combating infidels and heretics in ceaseless military and naval campaigns, until its hateful national theodicy was thoroughly discredited by defeat, bankruptcy, and impoverishment.

But this was all in the future for the adolescent Teresa. Just as she had as a girl, Teresa as a teenager absorbed the “truths” of her culture and acted like “a remorseless logician.” This time, instead of seeking martyrdom by being beheaded, she decided to become a nun and enter the convent of La Encarnación in Avila.

The Terror of the Agreeable

Teresa’s decision to become a nun nearly killed her several times.

She took the Carmelite habit when she was about twenty-one and described the mental and physical agony caused by leaving her family home as “every bone in my body seemed to be wrenched asunder.”

There seems to have been two problems. First, despite a gregarious, extroverted and passionate personality, Teresa committed herself to a life of celibacy, throttling her newly emerging sexuality with complete renunciation.

Second, and paradoxically, life in the convent turned out to be very pleasant, indeed. The privileged environment did not seem to promise the penances and purgation the guilt-haunted Teresa sought in order to assuage her existential terror in the aftermath of the mysterious relationship with her female cousin.

The convent La Encarnación lodged many daughters of Avila’s wealthy and powerful families, and Teresa’s father was the richest of them all. Nuns bought and sold the best rooms, which were spacious and even two-storied, between themselves, and those from upper class backgrounds were addressed by their aristocratic titles and sat in the best seats of the choir. Their personal servants prepared their meals, while poorer nuns lived in common dormitories and ate whatever the convent was able to provide. The nuns from wealthy families wore habits of fine cloth which included fashionable decorations, while the rest of the nuns wore simple habits provided by the convent. Until decades later when she instituted her reforms, the nun Teresa de Jesus was routinely addressed as Doña Teresa de Ahumada.

Teresa de Jesus as a young nun in La Encarnación de Avila. Original art created by the author with Midjourney

Ironically, Teresa’s psychological distress was heightened by her comfortable circumstances. Terrified as she was by her own seemingly unexpungeable sins, the genteel, even luxurious reality of life as a Carmelite nun did nothing to assuage Teresa’s fear of her impending doom in the afterlife. Given the assumption of Purgatory, she was too logical to believe the life of an aristocratic nun would save her from interminable eons of agony after death. This combination of Teresa’s brute repression of her own sexual energy, and the unmitigated psychological stress of her terror of Purgatory, almost killed her.

By the age of twenty-five Teresa was an invalid who nearly died several times. The list of the symptoms she suffered is extensive: heart pains—including spasms, vomiting, cramps, uncontrollable trembling from her head to her feet, temporary paralysis, fainting fits, anxiety, constant fever, prolonged periods of unconsciousness, wracking whole-body pain, sore throats, noises in her head, and intense headaches.

While the long years of illness may have initially reflected a sensitive young woman in an untenable situation with no way out, her health became precarious. At one point, Teresa was read the last rites and hot wax was dripped on her eyelids; she was totally unresponsive. Only her father’s refusal to proceed with a funeral saved Teresa from being buried alive. Illness was common among nuns, and probably for similar reasons, but Teresa suffered more than most.

The bewildering array of symptoms, and their near-fatality, may have signaled a dangerously compromised immune system. In our day, many people who have experienced trauma or extended periods of chronic negative affective states such as anxiety, depression or loneliness—often intelligent, well-educated, upper-income women—also suffer from suppressed immune systems which seem related to the complex and mysterious conditions of fibromyalgia, chronic fatigue syndrome, and Long Covid.

The Spanish Inquisition and believing “The Theology”

The greatness of Teresa’s achievement originates in her decision to conduct private experiments on her own consciousness to guide herself beyond the abstract doctrines and conventional religious practices of the Spanish Catholic Church. She developed her own empirical methodologies and applied them with the bold instincts of a spiritual scientist. Eventually she achieved states of the highest consciousness by independently re-discovering practices from other world cultures with which she had no personal contact. These were the spectacular spiritual experiences for which “Teresa of Avila” is famous.

To truly appreciate the magnitude of Teresa’s achievement, we have to understand the risks she accepted during those years of private spiritual research. The Spanish Catholic Church was shaped by its triumphalist interpretation of the events of 1492 and funded by the extraordinary wealth pouring in from the Spanish empire in the New World. The Spanish monarchy used these funds to launch attacks on all its perceived enemies, foreign and domestic.

One of Catholic Spain’s earliest opponents was the Pope. For centuries, the Roman Catholic Church in Rome, which was at the center of the Italian Renaissance and its humanizing and liberalizing influences, was more humane, liberal and open to new ideas than the Spanish Catholic Church. In 1527 when Teresa was twelve, a Spanish army sacked the city of Rome, inflicting the worst death, rape and destruction suffered by a Roman population in over a millennium, since the Sack of the Visigoths in 410AD. After the catastrophe, and until the final defeat and bankruptcy of Spain almost a century later, the Pope was subservient to the Spanish monarchy.

It’s also not well known that the Spanish Inquisition reported directly to the Spanish monarchy, not to the Pope in Rome. The Spanish Inquisition had officially been established in 1478 to identify and punish converted Jews (Conversos) who continued to secretly practice Judaism. The terror unleashed on the most productive segment of the Spanish population just happened to be a major revenue generator for the Spanish monarchy, as the wealth of the executed victims was assigned to the royal treasury.

In its first forty years of operation, the Spanish Inquisition tortured and burned at the stake several thousand men and women accused of secretly practicing Judaism, the vast majority of whom were almost certainly sincere Catholics. During those years the Spanish Inquisition confiscated an estimated ten million gold Ducats. Remember that these horrible judicial crimes began ten years before Columbus discovered America. The wealth expropriated from its victims was equivalent to 12% of all the gold and silver received by Spain from the New World between 1503 – 1555, one of the greatest transfers of wealth in history.

The activities of the Spanish Inquisition tailed off in the 1520s as the immense streams of gold and silver from the New World began flowing into the Spanish treasury.

But then mission creep began, and the Spanish Inquisition began to focus less on Conversos secretly practicing Judaism and became alert to those circulating disinformation from northern Europe. Nevertheless, for decades ahead the Spanish Inquisition remained especially suspicious of Conversos and women, considering both groups to be inherently unreliable Catholics.

Teresa de Jesus was both a member of a prominent Converso family and, of course, a woman.

The Truth and the Misinformation

Two years after Teresa’s birth in 1515 a German monk named Martin Luther nailed his 95 Theses to the door of a Catholic Church in the German town of Wittenberg, over a thousand miles to the northeast of Avila. One thesis questioned indulgences, and by implication the existence of Purgatory. From the perspective of the Catholic Church, it was an act of deceit and treason, misinformation that posed a fundamental challenge to the European establishment.

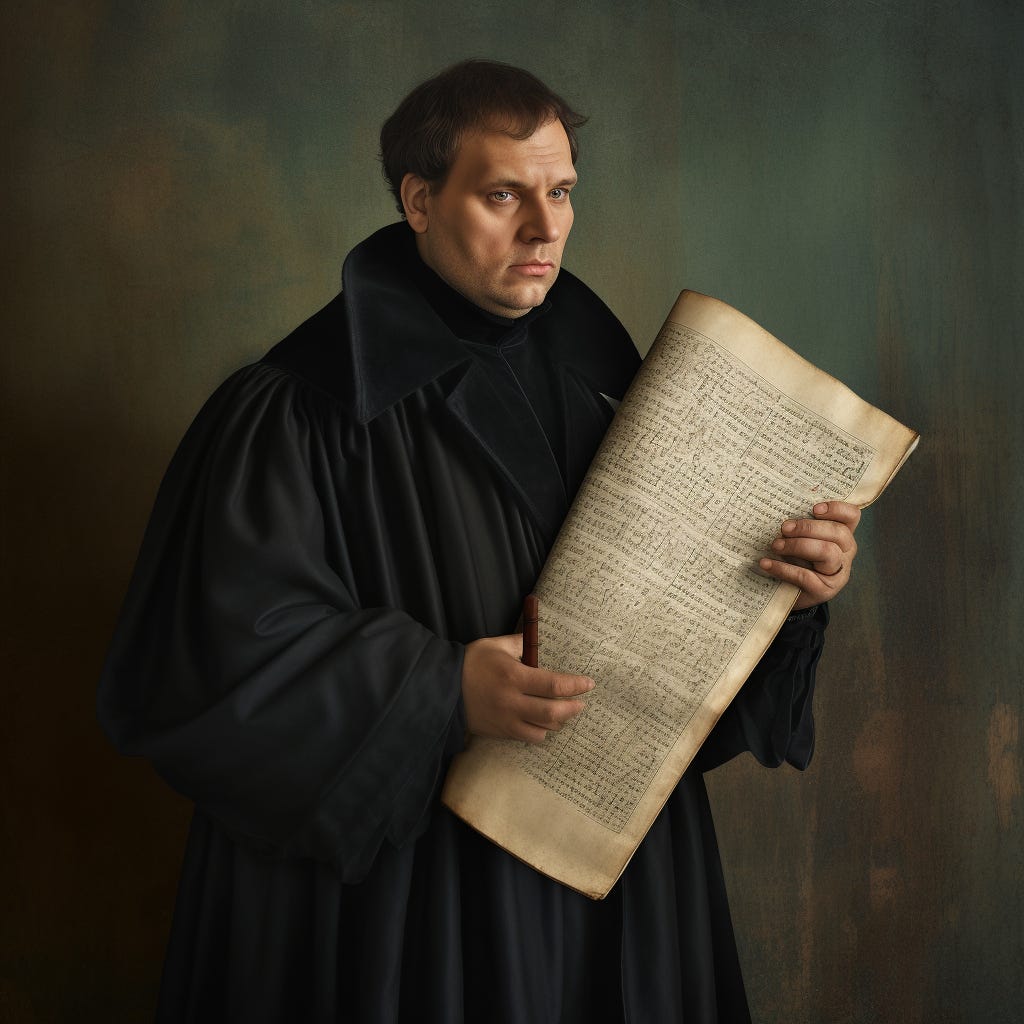

Martin Luther with his 95 Theses, based on the portrait by Lucas Cranach the Elder. Original art generated by the author via Midjourney.

Luther’s new ideas actually made Teresa’s search for authentic religious experience far more difficult and dangerous. It wasn’t Luther’s ideas themselves that caused problems for Teresa, but the government response to those ideas. Roman Catholic Europe as a whole, and Spain in particular, reacted like an immune system confronting an external threat to the health of the body by dispatching white blood cells to identify and destroy the foreign invaders.

The significance of Luther’s 95 Theses wasn’t that they conveyed powerful new arguments, it was that ordinary people were able to read them because of Gutenberg’s invention of the printing press. The medium was the message. No longer were ideas bottled up in hierarchical, authoritarian institutions and universities where unwelcome ideas could be labeled “misinformation” (actually, they were called “heresy”), swiftly squelched, and their proponents severely punished.

The effect was as dramatic on 16th century Europe as the adoption of the Internet in the mid-1990s was on our world. Within two weeks Luther’s 95 Theses were available all over Germany, and within two years were circulating widely in England, France and Italy.

But not in Spain.

The Spanish monarchy and its Spanish Inquisition understood that the “misinformation” was being carried into Spain by books and cheap printed tracts from northern Europe. The Spanish Inquisition launched a massive surveillance program to identify people influenced by the new ideas. They were contemptuously labeled “Alumbrados” (Illuminated Ones) and rounded up, tortured and executed by the Spanish Inquisition, often by being burned at the stake.

The ruler of Spain was now Emperor Charles V, and in 1521 he called a European council and summoned Luther to appear and defend himself. As a result, Luther was condemned—and would have been burned at the stake had he not been spirited away by sympathetic German princes and hidden away for several years.

As Teresa began her anguished search for truth as a young nun, the atmosphere in Spain became increasingly repressive and authoritarian. Spain was building the first truly global empire and its policies set the tone for the rest of Europe. In Poland, even farther away from Spain than Wittenberg, the genius Copernicus had prudently waited to publish posthumously his ground-breaking thesis proposing that the Earth revolved around the Sun. Copernicus was a devout Catholic and a canon, but the Roman Catholic establishment and its royal political allies were as invested in the idea that the Earth was the center of the universe as they were in Purgatory.

At least the Copernican theory could be empirically tested—eventually. The trouble was that measurement instruments were so primitive that the data was corrupted and unreliable, so for a century the debate raged between allies of “the truth” of the traditional terracentric universe and proponents of “the misinformation” of the heliocentric universe. As late as 1633, Galileo was condemned and forced to recant for circulating the “misinformation”.

We may laugh and shake our heads at what seem absurd, and tragic, controversies from an ignorant, pre-scientific age. It’s embarrassing to think how barbaric Europe was only a dozen generations ago. In our empirical, evidence-based, data-driven 21st century surely we are immune from accepting ideas based solely on authority rather than the science. All we have to do is confirm “the science” and the correct public policy is clear, surely.

Cognitive Neurology and the Bill of Rights

We have seen how Teresa’s age was shaped by deep assumptions accepted as the truth. But every age is shaped by deep assumptions shared by most people, and those assumptions are accepted as evidence-based. Over a decade ago, one of my sons was taught in his undergraduate cognitive neuroscience class that because the same part of the brain lights up when a person is physically hit or verbally insulted, “science proves that speech is violence”. It was an assumption that shaped transformative beliefs in both his personal life and in the way he and his generation viewed social and political issues.

What educated liberals of my generation still believe to be true of speech (Lenny Bruce: “I just said it—I didn’t do it!”) seems to my son and many others to be callous and clueless, at best, and at worse cruel and even criminal assault. This was the generation that insisted on “safe spaces” and “trigger warnings”—all very reasonable, even essential, if you share the assumption that controversial speech is equivalent to violence.

The American First Amendment’s protection of speech is based on the assumption that truthful speech will unmask false speech and allow well-informed citizens to makes decisions based on evidence-based reality. In recent years, the Covid crisis and the numerous controversies over the origin, lethality, and best treatment for Covid further challenged the assumptions on which the Bill of Rights are based. Many Americans older than my son and his contemporaries developed adjacent concerns about free speech. Controversial speech is now widely considered not only equivalent to violence, but metaphorically toxic, septic and infectious.

When speech perceived to be false is seen as polluting the pure ocean of truth publicly available on TV networks, traditional media, and social media, the founding American principle of freedom of speech begins to look reckless and dangerous, itself a threat to America and the wellbeing of Americans. Today, perhaps for the first time since 1789, a majority of Americans support restrictions on free speech:

https://www.pewresearch.org/short-reads/2023/07/20/most-americans-favor-restrictions-on-false-information-violent-content-online/

Like the belief that controversial speech is equivalent to violence and that false speech is dangerously infectious, if you believe in Purgatory it changes everything.

The Overton Window

The Overton Window, according to the Oxford English Dictionary, is the spectrum of ideas on public policy and social issues considered acceptable by the general public at a given time. Luther widened the Overton Window of 16th century Europe by allowing ordinary people to decide for themselves what they thought about Purgatory, and ultimately about the Copernican theory and many other ideas.

In Teresa’s Spain the Overton Window was defined by what authority figures said from the pulpit and vigorously enforced by the Spanish Inquisition. Religious orders were granted a slightly wider Overton Window than the rest, because they were constantly surveilled and under tight control.

As Teresa recovered her health she had access to devotional books from northern Europe that twenty years later in 1559 were to be put on the Forbidden Index. But Teresa explicitly discounted the value of book learning, “I have suffered greatly, and lost much time, because I did not know what to do; and I am very sorry for those souls who find themselves alone when they come to this state; for though I read many spiritual books . . . they threw very little light.” (Autobiography, Page 172)

It was by conducting empirical experiments in spiritual techniques that Teresa learned to achieve states of higher consciousness. The key question is, how did Teresa protect herself during these years from the fatal consequences of being charged with promulgating misinformation instead of Spanish Catholic truth?

It is often observed that Teresa personally knew the most powerful figures in Spain. That is true, but she knew they would not tolerate misinformation. Her closest friend was the Duchess of Alba, whose husband the Duke of Alba executed Count Egmont, a devout Roman Catholic and loyal military commander of the Spanish Army. Count Egmont’s crime? He objected to the arrival of the Spanish Inquisition in Belgium and the Netherlands (which proceeded to kill 6,000 people in a few months).

King Philip II himself was also a good friend of Teresa. But when the Spanish Inquisition reported to King Philip II that one of his friends and a trusted military commander, Don Carlos de Seso, was a Protestant, the King had Don Carlos tortured for fifteen months and then burned at the stake. Don Carlos was so injured from torture he had to be propped up by two men as he was led to the stake. He called out to King Philip II, “Is this how you treat innocent subjects?” King Philip II replied, “If it were my own son, I would fetch the wood to burn him, were he such a wretch as you are!”

In the next post we will present the inspiring story of how Teresa de Jesus managed to evade the terrible censorship and harsh punishments of the Spanish Inquisition, and break through to extraordinary spiritual heights, despite living in the most forbidding of all environments.

This is fascinating Chris, and so well-written. Definitely primed for Part 3. The question that arises for me is how to reconcile the way a punishing personal psychology can motivate acts of such rare and high achievement, as it has in many domains of human enterprise. But to have an aberrated view of one's self psychologically (i.e. I'm a terrible wicked sinner who is on the way to hell) motivate efforts that produce a pure view of one's Self spiritually is quite the phenomenon to consider. But my introduction to the particulars of this circumstance with Teresa are only from your articles so far, so I guess I'll have to wait for further installments to hear your full take on her journey. Thank you for writing this!

I loved the way you draw lessons from history and apply them to the present, Chris. Can't wait for the next edition!