Nicole's Voice

Jesus said, “You do not know what you are asking. Are you able to drink the cup that I drink . . .?” They replied, “We are able.” And Jesus said to them, “You shall drink indeed of my cup . . .”

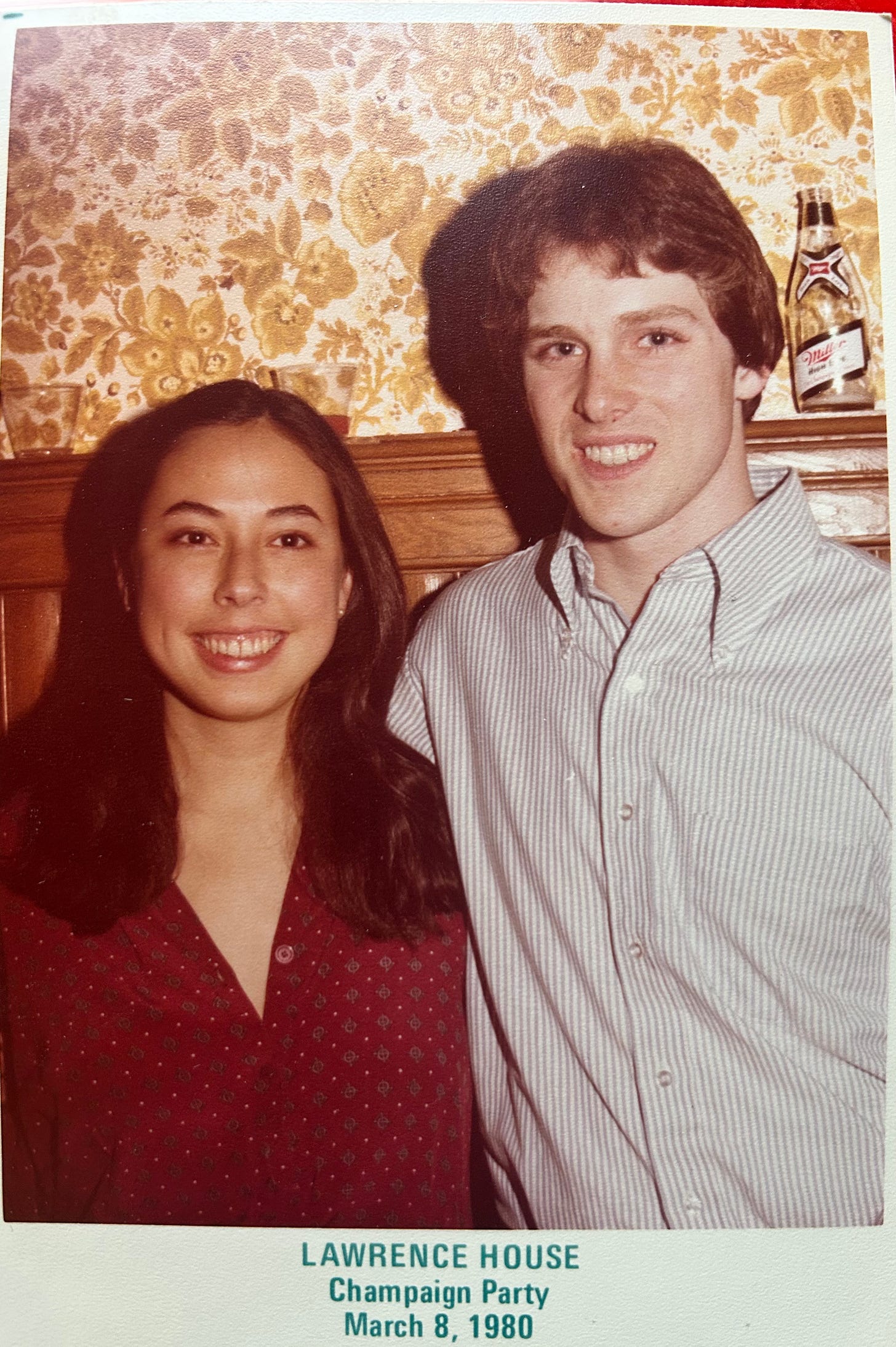

Shortly after seeing Nicole in San Francisco and starting my freshman year at USC, I wrote to her at Smith College. We had both been confused and dismayed by our reunion the month before in San Francisco.

Nicole replied immediately, on September 12th, 1978. She too sensed something went wrong during our reunion in San Francisco after three years of apart, and her letter started with uncharacteristic warmth: “Dear Chris, Hey, it was good hearing from you! I got the impression you didn’t want to write anymore. I’m glad you do.”

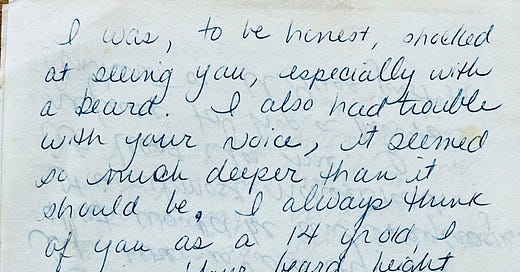

Nicole acknowledged she had been tense in San Francisco:

“I was, to be honest, shocked at seeing you, especially with a beard,” Nicole wrote. “I also had trouble with your voice, it seemed so much deeper than it should be. I always think of you as a 14 year old, I guess. Your beard, height + voice contrasted so much with what I remembered of you. Can I say something? Ignore if you think best, but in my opinion you should shave off your beard.”

San Francisco had been the first time we met after parting in Seoul, Korea three years before. I never knew how deeply Nicole felt about me the day I left Korea—but I knew how much I loved her. Our three years of letter writing in high school had confirmed our special relationship. So I was surprised when we were like strangers again during our disastrous meeting in real life in San Francisco. But in our first letters after meeting, we both hurried to re-establish our mutual understanding.

Last month I found a file of about dozen letters I hadn’t seen in over forty years. As I read these letters for the first time in decades, I suddenly heard again the voice of Nicole in her late teens and early twenties.

In her letter from Smith College Nicole addressed the question I had asked her in my first letter to her after meeting in San Francisco. With the challenges and temptations that would be facing us in college on my mind, I’d continued the earnest tone of our letters for the past three years, asking her “Have you ever made a conscious decision to hold to certain standards of conduct?”

In her letter of reply, Nicole responded by declaring her lack of interest in college social life, and assured me of her commitment to high standards:

“I could say that the social life here is scanty, but that would be an exaggeration. It is almost non-existent. At least for me. I refuse to hop a bus to Amherst or UMass just to attend some boring beer party . . . . I don’t have a philosophy of life that I can write down, but certain things I’m sure of: I don’t need to drink, I’ll not smoke, I’ll be a virgin when I marry, family comes first before anything.”

It was a reassuring start to this new phase of our already-years-long relationship. She continued:

“It does sound prissy. But I don’t feel that way. I feel I have to set these standards for myself. If I don’t, no one will. It could be that I want to be different, + these standards are as good a way as any. And you? Do you set your own rules?”

I’m sure I replied with a ringing declaration of my resolve to live by my own values, and I’m sure I also confirmed my commitment to remaining virgin until marriage. I meant to marry Nicole, but I’m not sure how clear I stated it. I didn’t have to—I knew she knew.

Despite assuring each other of our common values, Nicole and I faced different challenges. By being admitted to Smith College, Nicole had successfully achieved her parents’ objectives for her. Moreover, she had proven her loyalty to her parents by sacrificing her personal dream of becoming a veterinarian. She had also been accepted to vet school at Eastern Washington University in remote, dusty Cheney, Washington. But it wasn’t the prestigious college Nicole’s father wanted her to attend, so Nicole had given up her dream and enrolled at Smith.

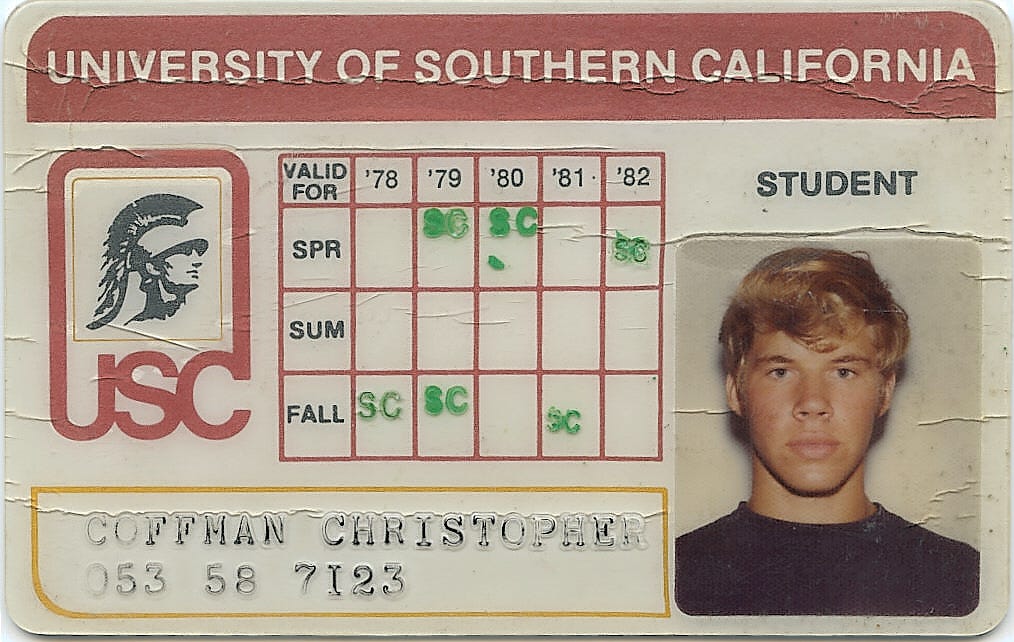

By contrast, at seventeen I had already disappointed my parents. My father had expected me to be accepted to Harvard, which in the year of the Supreme Court’s Bakke Case rejected my application. Instead, I was forced to attend the comparatively mediocre University of Southern California. USC cost almost as much as Harvard, but my parents loyally supported me and offered to pay for USC. I knew I owed my parents—big time.

Nicole was already a winner. In contrast, in the context of my family’s expectations I knew I was a loser, a disappointment, and I was determined to justify my parents’ faith in me and earn my way out of my ignominy.

In no mood for frivolity.

I was accepted to USC’s prestigious Thematic Option Honors program. The Thematic Option which would give me an excellent education, but I knew the distinction meant nothing to anybody outside USC. Still, I grasped with both hands the chance to earn redemption by laying the foundation to graduate at the top of my class in four years.

Almost every morning, as I looked at myself in the mirror while shaving, I’d reflect that in the Ivy League colleges on the East Coast that day, my contemporaries already had a three-hour head start on me. I’d wonder whether I’d be ahead or farther behind them after the next four years. I was determined to close the gap and exceed them.

I wasn’t going to accept a lowering of my trajectory in life just because I’d missed being admitted to Harvard.

We wrote each other every several weeks, as we had done for the three years in high school after I left Korea. Nicole, although blissfully unaware of my insecurities and self-hatred, was a constant reminder of the world I had missed qualifying to join.

On November 21st 1978 she wrote me, “Hi! How are you! I haven’t heard from you in a long time. Let’s don’t stop writing now—not after 4 years!”

We were eighteen years old—four years was a long time.

Before she finished her letter, Nicole wrote: “We had our first snow today. In a few weeks I’m going to wish I went to school in California. What are you studying? Write okay? I’d really like to know what’s happening with you,” and signed off, “Write soon, Nicole.”

Was she hinting she might transfer to California where we would be closer? Earlier in the letter Nicole discussed the possibility of transferring from Smith.

In her next letter, Nicole started by commenting, “You write such interesting letters. They’re worth re-reading and re-reading”.

Then she addressed various questions I asked her. She was still trying to decide if she wanted to continue at Smith College. I wasn’t happy at USC, either, and I’d told her so.

Nicole probed: “Why aren’t you happy at USC? Would you transfer?” But, as if to push back from any possibility she might be hinting I should consider coming to the East Coast, Nicole continued to respond to another comment I had made in my letter: “I don’t think wanting a great love is corny. I think it’s strange to admit it. I have a pessimistic view of marriage—it seems that after living together so long a couple would get bored. What keeps most marriages together anyhow? Children. Chris—I’m serious I can’t have kids. I would rather kill myself. Something’s wrong with me—that I feel so strongly about this.”

Her declaration didn’t surprise me. We’d known each other since eighth grade when I arrived in Seoul, Korea with my family.

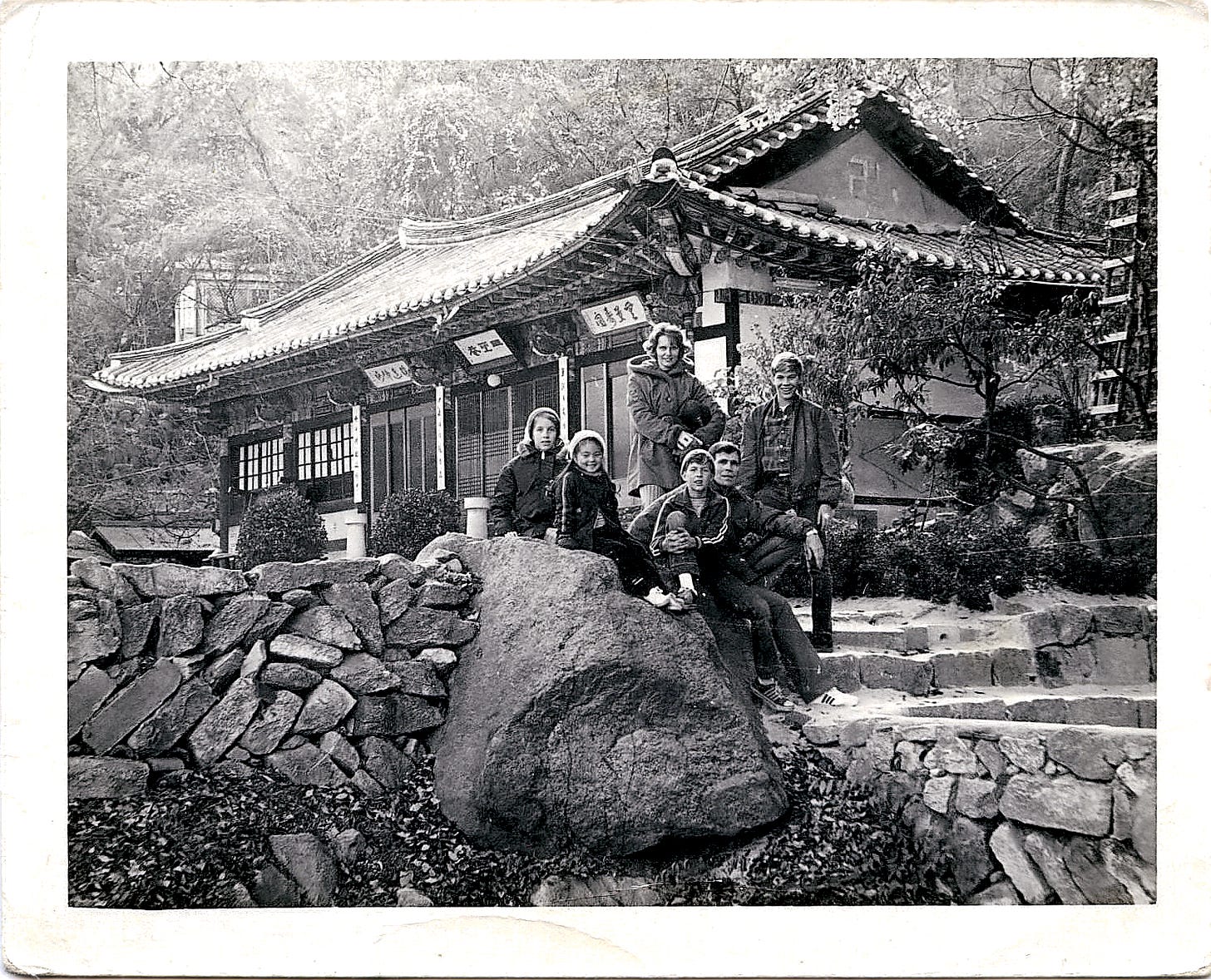

Arriving in Korea at the age of thirteen August 1974

Nicole was born in New York City when her Korean father was studying at Columbia University. Her mother was French Canadian and her parents had met in college in New Hampshire, but her family moved to Seoul when Nicole was seven and it was there Nicole and I met in school six years later.

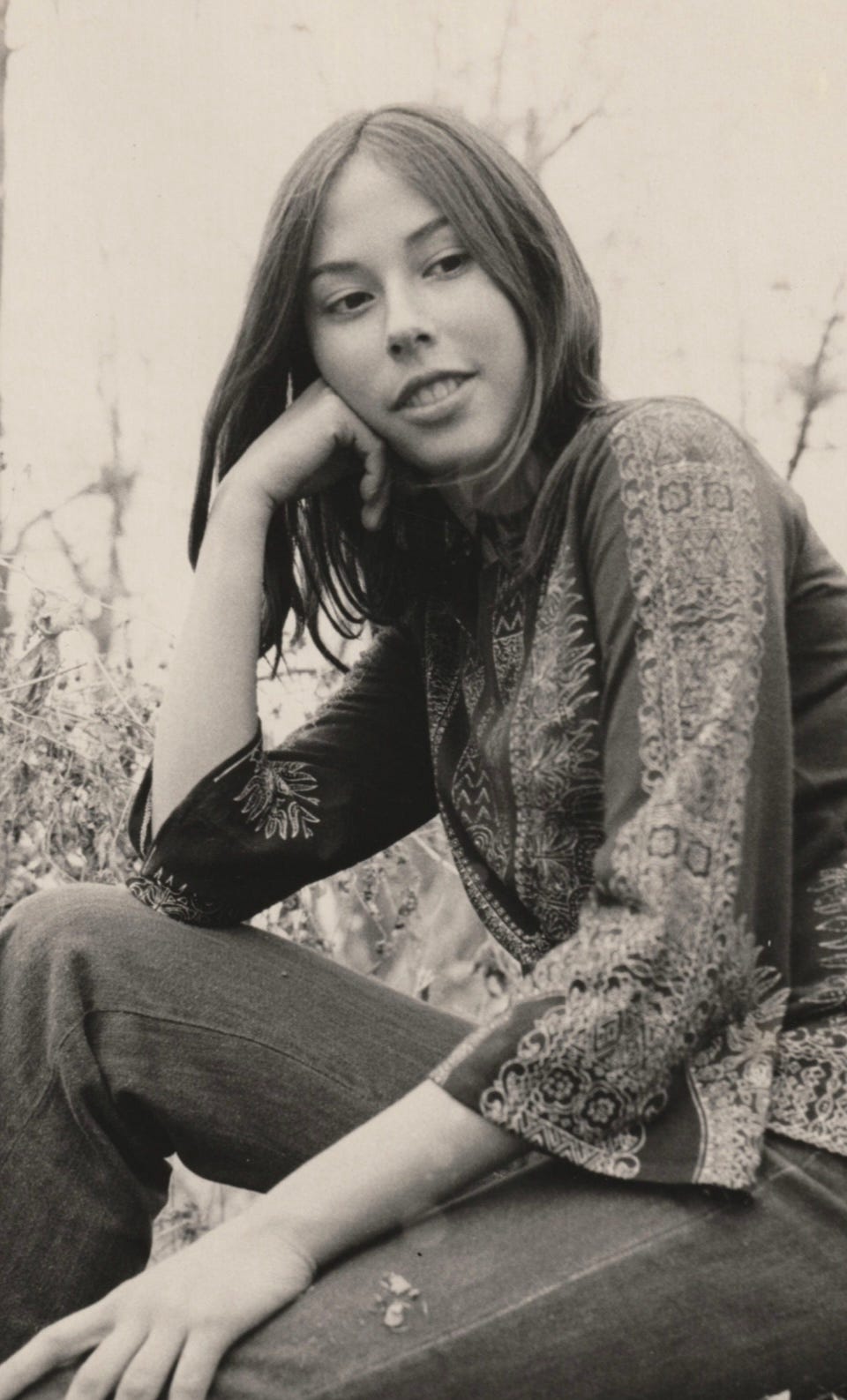

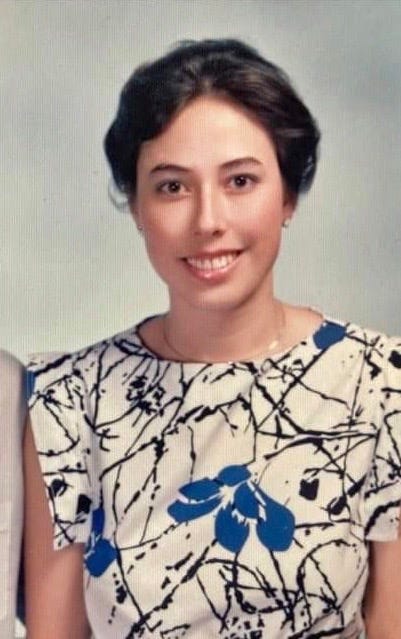

Nicole at the age of thirteen

In ninth grade Nicole and I became good friends and spent almost all our free time together in long conversations. That year I listened to Nicole repeatedly refer to babies in the womb as “parasites”—and she would insist she could never be pregnant. Decades later, Nicole’s best friend Susan also remembered the same thing just as clearly as I did.

So I took Nicole’s declaration in stride. My upbringing had taught me women were disgusted by sex, so even at fourteen I had interpreted Nicole’s description of babies as parasites as a slightly displaced, and understandable, expression of anxiety about sex.

Similarly, I interpreted her letter as a reaction to the predicament we were both facing, being at college unsupervised and feeling pressure to have sex. I didn’t consider Nicole to be directing her feelings primarily at me: I understood her statement as her declaration of rebellion against the male students at nearby Amherst College who were Nicole’s main social contacts at Smith.

After declaring she would rather die than have children, two paragraphs later Nicole blew hot again—or at least puffed warmly—writing, “My number is 413-584-4605. What’s yours?”

Of course, I accepted her implicit invitation and called Nicole. Our phone call must have been wonderful. Just before leaving Smith for the Christmas holidays, Nicole sent me a Christmas card. Nicole too seemed to be still glowing from our telephone conversation:

“Dear Chris, Somehow, sending this card to all my friends and relatives was right—tell me why it feels so funny when I think of sending it to you? Maybe it’s because ‘nice’ isn’t an adjective I’d use to describe you. I DON’T MEAN ANYTHING BAD! It was fun talking on the phone the other day . . . “ and, seeming to confirm that our phone call had warmed her to being in a relationship with me, she signed the card, “Take care, Love, Nicole.”

Nicole and I were both avid readers and books influenced us deeply. The books we read were very different, and we never discussed those books that had the strongest impact on us. For example, Nicole never mentioned to me the book that had a pivotal influence on her life, Robert Heinlein’s Time Enough For Love.

Heinlein spent time in Greenwich Village in the 1920s at the same time as Henry Miller, and like Miller absorbed the “free love” ethos. At fifteen, Nicole encountered a variation of the Henry Miller worldview almost five years before I was to read Tropic of Cancer.

Time Enough for Love is set thousands of years in the future, and concentrates on an elite family who have been bred by scientifically combining genes into a superior group of intelligent, talented, and attractive people. Advanced genetic analysis has replaced religious or social taboos and so the family members are all sexually active with one another. Biotechnological rejuvenation processes mean that even fathers and mothers who are thousands of years old have the appearance and energy of thirty-year-olds, and they ardently enjoy sex with their own children and other family members. The dominant theme of Time Enough For Love is a guilt-free approach to bacchanalian sexuality in elaborate orgies staged by the family with each other, and the always-on, always-enthusiastic attitude of the women, who are immediately ready to have sex with each other, or with any of their male family members.

The novel opened Nicole’s eyes when she read it at the age of fifteen. Its depiction of women enthusiastically ignoring social limits and eager for sex assuaged a trauma inflicted on Nicole two years before. It was a trauma that shaped our relationship from its beginning, although I never knew exactly what had happened.

When Nicole and I first became close friends, she told me immediately that a previous boyfriend the year before, whom I knew, had done something to her. She wouldn’t say what it was, but she rolled her eyes and shuddered with revulsion. My response was to spend the next year committed to proving to Nicole that not all boys / men were like her previous boyfriend, and that Nicole could trust me. I effectively handed Nicole control of our relationship, hoping Nicole would eventually trust me and want to be closer to me.

I didn’t know for decades what had caused such revulsion in Nicole. As it turned out, what happened began at an eighth grade dance the year before, when her boyfriend was sitting at the edge of the dance floor and he pulled Nicole onto his lap. Nicole sat on his lap, and one of the adult chaperones called Nicole’s mother and reported the incident.

Nicole’s mother, who was raised by nuns, flew into a towering multi-day rage and forced Nicole to stay home from school for a week as punishment. Nicole was thoroughly shamed and humiliated, and as her mother had hoped Nicole internalized her mother’s shaming.

When we got together a year later Nicole was, in fact, ambivalent about boys and resistant to being touched, and for the first couple months she exuded a feeling of tension, suspense and readiness for immediate retreat when we were together.

After a year, I proved myself to Nicole and her parents. Now Nicole had a boy she liked and trusted, who her parents approved of, and she’d read Time Enough for Love and was recovering from the trauma inflicted on her two years before.

Nicole’s parents invited me to a party in their home at the end of our freshman year in high school. Nicole was finally letting go of her old issue and beginning to respond to me as the boy who had been loving and trustworthy for a year. After so much time talking, we had just started holding hands. Nicole and I both had high hopes for the night of her parents’ party. I wanted to slow dance with Nicole and hopefully kiss her, nut my parents demanded I come home after only two hours, just as the party was getting going. So Nicole and I didn’t have any chances that evening.

Hanging over our heads was the fact that my father’s two-year Army assignment was almost complete and he was about to be transferred to a new assignment in Germany.

My family in Korea

My parents made sure Nicole and I ran out of time.

After the party, in the early summer Nicole’s parents invited me to join their family on vacation to Cheju-Do, a beautiful island off the coast of Korea south of Seoul. Without telling me about the invitation, my parents responded by basically deporting me from Korea. They sent me back to America almost two months before they themselves left Korea.

I didn’t find out about the rejected invitation to spend time with the Lees on Cheju Island until a letter from Nicole reached me in Germany at the end of the summer. The revelation my parents had declined the Lee’s invitation without even discussing it with me was crushingly bitter. If Nicole and I had been permitted a romantic time together in the warm, humid Korean summer on Cheju Island I was sure our love would have been established once and for all.

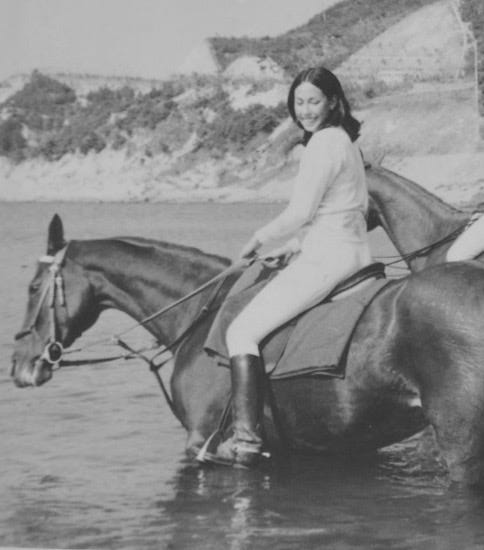

Nicole on Cheju Island a year after I left Korea

I wouldn’t know for decades how Nicole had felt the day I left Korea: she sat by her bedroom window the day I left and cried like her heart was breaking - which maybe, she had thought, it was. She’d lost me, and given our age and situation, there was nothing either of us could do about it. To Nicole that day, it had felt like the sky was suddenly empty of the sun, stars and clouds. She already missed me and grieved for what a relationship with him might have been.

Still, Nicole and I proved resilient and wrote each other for three years in high school, and then even after the setback of seeing each other in San Francisco in the summer of 1978, were back in frequent and trusting contact by letter and the occasional phone call.

So by the time Nicole and I were in our first year of college, separated by almost three thousand miles, we already had plenty of experience keeping our friendship going by writing letters.

We continued to exchange friendly letters for the rest of our Freshman year, and after Nicole’s finals were over and she was about to return to Seoul, Korea for the summer, Nicole wrote me a brief letter and concluded: “If you have time, I’d really like to hear from you. My Korean address is: N. Lee c/o Mr. Ki Chang Lee C.P.O. Box 5104 Seoul, Korea.”

Things changed our Sophomore year. Nicole and I were now 19. While we had previously omitted discussing how strong our feelings were for each other, being too shy to admit it, now the subjects we omitted were new experiences and ideas that made us restless to try new experiences in life, and given the great distance that physically separated us, inevitably exerted divergent pressure on us.

Nicole bought a copy of the poems of ee cummings that year. She drew an upside-down unicorn on the inside cover, a last expression of her innocent childhood fascination. I knew how much she loved unicorns, of course, and the summer before had bought Nicole a crystal unicorn in Italy.

Her beloved unicorns soon went by the wayside, probably because of the scorn of some sophisticated Smithie who recognized it as a phallic symbol tilted at the exact rampant angle—something about which Nicole would not yet have had any idea.

This edition of poems was part of Nicole’s awakening. It included two poems to which Nicole’s heart, soul and body deeply responded, and would some of ee cummings’ lines would always be interwoven with her deepest romantic feelings:

i like my body when it is with your

body. It is so quite new a thing.

Muscles better and nerves more.

i like your body. i like what it does,

i like its hows. i like to feel the spine

of your body and its bones, and the trembling

-firm-smooth ness and which i will

again and again and again

kiss, i like kissing this and that of you,

i like, slowly stroking the, shocking fuzz

of your electric furr, and what-is-it comes

over parting flesh….And eyes big love-crumbs,

and possibly i like the thrill

of under me you so quite new

And the other poem was:

i carry your heart with me (i carry it in

my heart) i am never without it (anywhere

i go you go, my dear; and whatever is done

by only me is your doing, my darling

i fear

no fate (for you are my fate, my sweet) i want

no world (for beautiful you are my world, my true)

and it’s you are whatever a moon has always meant

and whatever a sun will always sing is you

here is the deepest secret nobody knows

(here is the root of the root and the bud of the bud

and the sky of the sky of a tree called life; which grows

higher than soul can hope or mind can hide)

and this is the wonder that's keeping the stars apart

i carry your heart (i carry it in my heart)

She never mentioned the poems to me in her letters. Nicole put away her unicorn imageries and discarded the crystal statue I’d given her.

I had no inkling of this side of Nicole and her openness to thinking about sex. All I still knew was the young woman who wrinkled her nose and looked disgusted about the mysterious thing her former boyfriend had done to her, who called babies “parasites”, and who wrote me that she’d rather kill herself than become pregnant.

The letters we were writing each other were becoming gossamer filaments tossed across the continent, too frail to maintain our tenuous, contingent, and ever-postponed, union.

The first semester was hectic for both of us. Nicole had chosen to major in science and was taking a heavy load of Cell Biology, Organic Chemistry, Horticulture, as well as Music History and Asian Studies at Amherst—where there would be men in her class. Despite, or because of her intelligence, Nicole’s excellent academic performance didn’t quiet her anxieties and uncertainty about both her present and her future. She continued to consider transferring from Smith to Williams.

Nicole’s decision to focus on science was, in a sense, a re-framing of her original goal to become a veterinarian--both because she loved animals and was uncomfortable with people—but it was also an act of defiance: “I suppose a lot of my feelings stem from the resentment I feel when my parents & family (who are very music – art-oriented people) try to channel me in that direction.” Dutiful and conscientious in so many ways, Nicole was at last beginning to rebel and assert her independence.

Meanwhile, I pledged the ATO fraternity, while still taking Thematic Option honors courses as well as Calculus. My weekly Calculus tutorial was Thursday morning, and on Wednesday nights pledges would be up late, forced to drink excessive amounts of alcohol, and hazed—so when I did make it to the tutorial I was dazed from lack of sleep. I was dating girls on a very preliminary basis, and a couple times during alcohol-fueled fraternity or sorority parties ended up kissing dates I didn’t know or care much about, but I wasn’t serious and didn’t let it go any farther.

The girl I liked best reminded me of Nicole even though she was a beautiful Jewish girl from Dallas. She was intelligent, well-brought up, and a very attractive brunette with a sensational body. We went out a few times, including to an ATO costume party where it was my idea for us to dress up as Leonid Kozlov and Valentina Kozlova (both Bolshoi principals, an a married couple at the time) who had just defected in 1979 while on tour in LA.

Wendy cheerfully agreed to my idea, and we went to the Capezio store together in West Hollywood to get our gear, including of course the famous Capezio ballet shoes. Our costumes were far too high concept for a USC fraternity party, were most of my new brothers and their dates were dressed as cowboys and and cowgirls, Japanese, Arabs or Scottish highlanders:

Wendy and I had a great time at the party, but she was upset about the way the flash photographs revealed her pubic hair through the dancing tights, and stopped seeing me. She was actually on her way out of USC, anyway—after her freshman year she transferred to UT Austin. The rumour went around USC that the Theta sorority house at UT Austin didn’t accept Jews, so Wendy had applied to USC in order to be admitted to the Theta house at USC, and then returned to UT Austin where the sorority had no choice now but to admit her.

In my letters to Nicole I may have boasted too much about my drinking and partying, and given Nicole the wrong impression that I had abandoned her and was no longer keeping myself a virgin. Nothing could have been further from the case.

For whatever the reason, at the beginning of the second semester of our Sophomore year, the blow fell. Nicole began her letter in a way that I never have imagined would lead to what she was going to disclose. Since Nicole herself did know it, of course, there was an ironic logic to her first sentence. The letter was dated February 2nd 1980:

“Dear Chris,

I don’t want to get into a deep discussion of morality in this letter. But I do want to say one thing . . .”

Nicole proceeded to give me a stern lecture about I how had been distracted and was not applying myself hard enough to my studies. She sounded like a disapproving parent. I’ll quote the letter in full to illustrate how uncompromising and judgmental Nicole was being, despite her first sentence about not wanting to get into “a deep discussion of morality”. What I didn’t see as I absorbed Nicole’s criticism was that she wasn’t really talking about morality at all—her perspective was purely pragmatic, a utilitarian discussion of maximizing total pleasure across time:

“ . . . You’re depressed because of your grades, yet you said you had a good semester, but also that you didn’t put a whole lot of work into the Calc course. Does that make having a good time & getting good grades mutually exclusive? If someone asked you which was more important I’d guess you’d want to say ‘grades’, but would be thinking ‘having a good time.’ You want the grades now so you can have a good time later in life. Is that right? If you isolated yourself & just studied, not much social life with your new frat—would you be afraid of the peer pressure? I guess what I’m saying is—is getting top grades with the sacrifices you have to make now (not going to so many parties, not getting blown away so you can function the next morning, not spending so much time with friends) so you can “succeed” later? If it is, if getting into Harvard Law & having lots of money will make you happiest in the future—then you’ll just have to accept being not so happy in the present.”

Nicole obviously believed I was immature and irresponsible and needed to be reminded not to live for today. I actually needed no additional encouragement to loathe myself for what had happened last semester, when I had gotten two As and two Bs—the worst semester of my college career.

Nicole then continued in a vein I was minutes away from recognizing as an example of highly—and exceptionally painful—ironic misdirection:

“If I sound prim and prissy, sorry. I am. I’d like to say that I have a philosophy that I guide myself with, but I don’t & if I did, I’d merely spend my time finding ways to get around it.”

This was a warning I didn’t register, a reminder of the deeply rebellious part of Nicole’s nature. The last time she’d used the word “prissy” was the year before when writing to me that she was committed to being a virgin when she married—me, as I hoped.

Nicole continued in a conciliatory way, by declaring her belief in our shared values: “I think we both are very motivated to achieve, we both agonize about it. It seems there should be a balance between working hard & playing hard. Yet people”—she seemed to be including me in ‘people’—seem to be at one extreme or the other.”

Then her reflections took an ominous turn, veering from her belief in our shared value and asserting that we had apparently grown apart, and that she was skeptical of the authenticity of our relationship:

“Peoples’ lives seem so simple, especially when you no longer know them well. I can’t help the picture in my mind of you, all-American, talkative, social but cynical, success-oriented lawyer, although I guess that’s not how you see yourself.

“It’s easy to talk on the phone, where words are sort of fed to you. My replies to you are sometimes amazingly shallow, hypocritical. I don’t know exactly why, maybe because I’m afraid to speak freely, I don’t know you well, etc. We don’t know each other, Chris—you’re right.”

She then wrote, “I am Nicole Lee” and described how she sat at parties observing others, not participating, and how “I make rules for myself & and then break them simply because I don’t want walls around me. Yet, perversely, I need walls. I’m still so used to parents around, I think I’ve created them in my head. If I don’t come back to the dorm to sleep, I feel guilty.”

This disclosure rocked me to my core. I had realized years ago Nicole mostly didn’t say what she was thinking or feeling, and that her hints were almost always a pointer to a much larger reality. So she’d casually told me that she hadn’t come back to the dorm to sleep, and that she’d felt guilty about it—with the implication that maybe she shouldn’t feel guilty about sleeping with a man.

Nicole may have been signaling she was beginning to adopt my partying values, but in fact there was a misunderstanding, and she was now way ahead of me. I had repeatedly gotten very drunk, and been to many raucous parties, and had fooled around—up to a very limited point, with a couple dates—but I had never forgotten or been disloyal to Nicole at USC, any more than I had forgotten her on the island of Corfu two years before.

Nicole then continued, “I believe in God. Maybe because he’s the ultimate wall” and she closed her letter, “Chris, I hope we can meet some day. Just so we can satisfy our curiosity about each other, if for no other reason. You’re an interesting person. Hope you get over the Calculus depression. Tell me what your plan of attack for this semester is,” And then in a different color ink, written perhaps in a different mood, certainly a few hours or a day or so later, Nicole signed off by writing an enigmatic Koan, “seeker of truth / seek no paths / all paths lead where / truth is here. Love, Nicole”

Nicole had begun her letter by asserting “she didn’t want to get into a deep discussion about morality in this letter” and I had read her extended criticisms of my drinking and poor grades thinking that her reference to morality was about my partying and academic performance, which she was in fact severely and in detail critical about—when, in fact, she intended to let me know she was sleeping with other men. She claimed to be “prim and prissy” while she was now getting naked and having sex while I had kept myself virgin—for her!

I was devastated. It was the second greatest debacle of my life, even worse than not being admitted to Harvard and being shunted instead to USC.

I was sure Nicole’s decision was carefully considered. There was no way Nicole would allow herself to be pressured by a drunken preppie into having sex against her will. I knew Nicole had carefully chosen how, when, where and with whom to lose her virginity.

I never forgot Nicole’s letter or how I felt when I read it. Twenty years later, I wrote about a situation just like this in my novel Crisis Deluxe, when I gave these lines to the character Jacqueline, who was based on what I remembered about Nicole, and had guessed to be true:

“Well, losing my virginity was the single most carefully considered decision I have ever made. Probably including my two marriages—I think I was in a pretty irrational state of mine when I agreed to them. When I chose to relinquish my virginity I was stone cold sober, although it probably wouldn’t have been as bad if I’d had a couple of drinks.”

I had no way of understanding how Nicole’s decision about whom she first slept with was based upon the powerful way we had imprinted ourselves on each other during the two years we’d been together in Seoul. Neither of us realized it at the time, but in our long conversations we not only mutually shaped one another minds and understanding of the world. Our close, trusting, physical proximity for hundreds of hours didn’t just accustom us emotionally and psychologically to each other’s presence. Our bond was more primal than that.

I knew I loved Nicole, and that I was only attracted to other women to the extent they reminded me of her in some way. But I attributed my love to spiritual, emotional, psychological, intellectual and aesthetic factors—which was all true. But what was also true was that close proximity for two years in a relaxed and trusting atmosphere had instantiated one another’s pheromones deep into each of our sensory and nervous systems. We were united by our pheromones without physically touching each another. We had pair-bonded without anyone realizing it, including ourselves, becoming one another’s ideal romantic and sexual partners.

The unhappy result for me is described in Amy Winehouse’s song, “Love is Blind’:

“I couldn't resist him

His eyes were like yours

His hair was exactly the shade of brown (blond, actually)

He's just not as tall

But I couldn't tell

It was dark and I was lying down.”

“You are everything

He means nothing to me

. . .

Why're you so upset?

Baby, you weren't there

And I was thinking of you when I came.”

What do you expect?

You left me here alone

. . .

Don't overreact, I pretended he was you

You wouldn't want me to be lonely

. . .

No, he wasn't you

But you can still trust me, this ain't infidelity

It's not cheating, you were on my mind.”

Nicole’s first man was from Amherst:

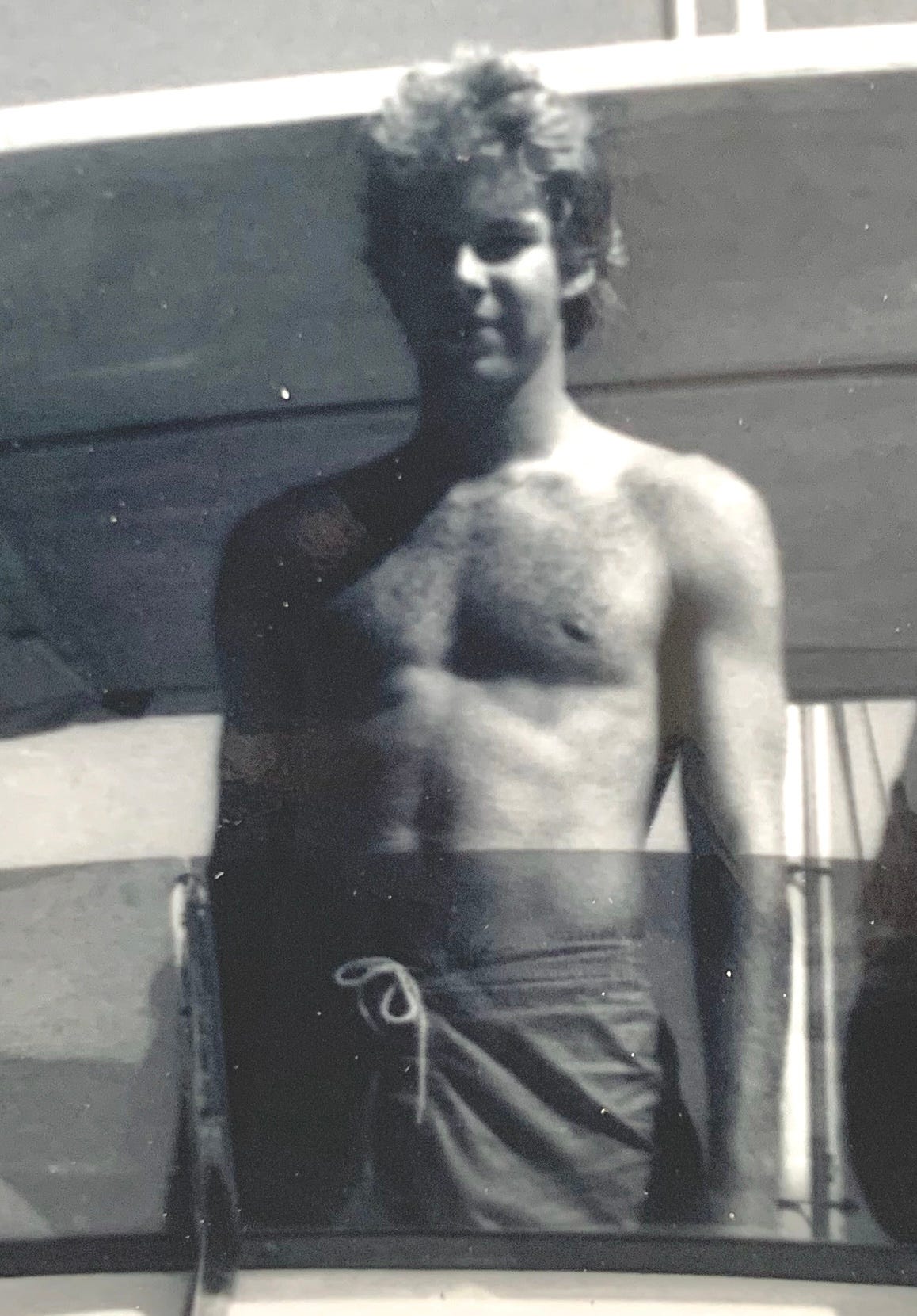

Cuckolded by my Doppelgänger

(a word Nicole had probably read for the first time in Time Enough For Love)

I had no way of knowing it at the time, but he could have been my brother, almost my twin:

Off the coast of Southern California 1980 - too far away

Nicole had given me a bitter cup to drink. I realized, of course, that Nicole could do anything she wanted. Nicole was an independent person and I had no claim on her. We had never even kissed.

I also knew the terrain in our lives about which we didn’t write to each other had been growing larger and larger, and was now vast. I had never told Nicole, for example, about why I didn’t lose my virginity on the island of Corfu two years before, much less that it was out of loyalty to her. I had never told Nicole I wanted to marry her one day—much less actually asked her to marry me. How could she know how I really felt, deep in my heart? Now Nicole had crossed over into “that undiscovered country” without me.

On one hand, objectively, I’d simply had the bad luck to be in the wrong place—Southern California—for too long. Nicole was a beautiful, intelligent, desirable young woman who’d spent two years in college in Massachusetts. That was that. It was a recapitulation, at a higher and more painful level, of what had happened in the summer of 1975 when my parents exiled me from Korea. Once again, I was powerless, without the resources necessary to change my circumstances, no matter how deeply I had wanted them to be different.

But emotionally, it wasn’t so simple or matter of fact. Personally, I was committed to Nicole with all my heart. Nicole’s news was painful and difficult to bear.

I didn’t feel threatened by this guy, whoever he was. My intuition told me he had no chance of developing the level of intimate understanding and trust shared by Nicole and I.

But what I could do? Nicole was a shy, introverted person who was uncomfortable with directly discussing personal matters, especially those charged with emotion. That was one of the reasons I so cherished our special understanding—I knew how rarely Nicole confided in others. Nicole signaled with hints, rather than stated anything explicitly. I was well aware that I couldn’t comment too directly about what she had written, or seek to clarify it, without triggering Nicole’s reserve. I didn’t know how to respond.

Two weeks later Nicole still hadn’t heard from me and on February 19th she wrote,

“Dear Chris,

Has our marathon letter-writing ended? I hope not!

Talk about February blues—I have a terrible case of them. At the risk of complaining too much, I’ll say this—I now know what an ant feels like doing the same things day after day. I envy your California weather.”

Nicole then asked, “Are you going to go away for your junior year?”

Nicole continued her letter on February 27th and wrote in closing, “Listen, it’s not always you write to one person for 4 years—don’t stop now, all right? Nicole”

I must have replied, but my letter or letters are now lost, and on June 9th Nicole was still feeling uneasy about what had happened to our relationship and wrote me from Korea:

“Dear Chris,

“First of all—I realize you’ll probably never talk, write or otherwise communicate with me again—it’s my fault & I really do apologize for not writing. So this is my attempt to make up for it.

I hope things are all right at home. Have you found a job? How did finals go? (I’d really like to know—I’m not just asking.)”

She discussed the shaky political situation in Korea that summer of 1980, after the assassination of the President of Korea the previous October. Then she continued,

“Luckily, my parents understand about transferring to Williams.

“I can’t say that for other people, though. I’ve gotten reactions ranging from “Oh, good idea. You’ll meet a fine husband there.” To “Oh, didn’t like the nunnery, huh?” I gave up trying to explain. Now I just say I wanted a change of atmosphere. True enough. Although if that were the whole reason I would have gone to USC. From what you say, I’d be in for another culture shock.

“Chris, do you think we’ll ever meet again? Do you think that if we do, we’ll each be so different from what we imagined that we’ll get disillusioned? In that case we should just write & talk on the phone. No, I take it back. When you get back from Mexico and come to the staid & conservative stuffy East Coast, call me.”

Nicole clearly hadn’t decided to end our relationship because she’d started having sex.

I had a decision to make.

Paradoxically, it was the religious beliefs that had motivated me to stay a virgin which now guided me to remain true to Nicole and to pursue my dream of marrying her. I was a careful reader of the Bible and my readings encouraged me to restore my relationship with Nicole. The cup I was being offered was the very cup quaffed by God himself.

God is commonly associated with attributes like power, glory, honor, omniscience, omnipotence, and so on. When we use the word “godlike” we think of great beauty and dignity and superhuman abilities and complete mastery of the universe. That’s understandable, because it’s true.

But the reality is that God mostly chooses to express his divine powers by loving us in ways that are many orders of magnitude more intense and passionate than we humans are capable of expressing our love.

The Gospel of Mark recounts the story of what happened when Jesus Christ’s disciples realized just how powerful he really was. The mother of two of them came to Jesus and asked whether her sons James and John would be permitted to sit at the places of honor on either side of Jesus when he had conquered the Romans and established his kingdom, as they imagined was his goal. Jesus responded by asking them, “Are you able to drink the cup that I drink?”

They assumed he meant a cup of power and honor and glory—royal responsibilities and duties—and they said, “Yes, Lord, we are able.”

The irony running through the Gospels is the vast gap between what the disciples and followers of Jesus thought their future would be like and what the future really held. Jesus knew exactly what the future would bring: beatings, whippings, abuse, mockery, and finally death on a cross. His disciples would all die terrible deaths as martyrs as well. This was the cup Jesus was offering, and he said to his uncomprehending disciples, “You will indeed drink of my cup.”

I knew from reading the Bible that one of the most common images used by the Old Testament prophets to portray God is as the husband of a beautiful but wayward wife who is repeatedly unfaithful to him. The divine husband ignores the countless lovers she takes and pleads with her to return, eventually welcoming her return with love and acceptance:

“For your Maker is your husband,

the LORD of hosts is his name;

the Holy One of Israel is your Redeemer,

the God of the whole earth he is called.

For the LORD has called you like a wife forsaken and grieved in spirit,

like the wife of a man’s youth when she is cast off,

says your God.

For a brief moment I abandoned you,

but with great compassion I will gather you.

In overflowing wrath for a moment I hid my face from you,

but with everlasting love I will have compassion on you,

says the LORD,

your Redeemer.”

(Isaiah)

Of course, Nicole and I weren’t even engaged, much less married, and Nicole was a well-brought-up, intelligent and sensitive Smith College student who was simply exercising her right to make her own personal choices.

Yet the life-affirming nature of divine love is inspiring. God exercises his great power through an almost unimaginable divine love that heals and redeems. The prophets show this by the truly spectacular scale of the flamboyant sexual adventures of God’s beloved, who created an astonishing test of God’s love that surely only a divine being could pass. Despite her epic and passionate affairs with innumerable lovers, God continues to long for his wife and passionately love her:

“Upon a high and lofty mountain you set your bed . . . .

you uncovered your bed,

you have gone up to it,

you made it wide;

and you made a bargain for yourself with them,

you loved their bed,

you gazed on their cocks . . .

You found your desire rekindled,

and so you did not weaken.”

(Isaiah)

How well you direct your course to seek lovers!

So that even to wicked women you have taught your ways.

(Jeremiah)

On every high hill

And under every green tree

You sprawled and played the whore

. . . .

Look at your way in the valley;

Know what you have done—

. . . Who can restrain her lust?

None who seek her need weary themselves;

. . .

But you said, “It is hopeless,

For I have loved strangers,

And after them I will go.”

(Jeremiah)

. . .the days of her youth,

when she played the whore in the land of Egypt

and lusted after her paramours there,

who had cocks like donkeys,

and spouted come like stallions.

Thus you longed for the lewdness of your youth,

when the Egyptians fondled your bosom

and caressed your young breasts.

(Ezekiel)

God’s predicament was spectacularly more dramatic and confronting than anything I was being presented with in my life. Despite his beloved wife’s epic sexual adventures with other lovers God is shown to passionately love his wife and desire her, and to persistently long for his wife to willingly return to their marriage. He wasn’t threatened by her countless lovers.

Speaking through the prophet Hosea, God said “I will heal their disloyalty. I will love them freely . . . It is I who answer and look after you. Your faithfulness comes from me.” The divine example presented an infinitely more demanding standard of love than I was being asked to achieve.

God’s unquenchable powers of love inspired me. Jesus commanded his followers, “Take up your cross and follow me”, but for the vast majority of us the image of crucifixion is only a metaphor for life’s routine challenges. God subjects himself to tests infinitely more agonizing than anything he asks of us. Similarly, I was being offered an extremely diluted version of the cup from which God had shown himself willing to drink.

My decision was clear: I would drink it. I was still deeply in love with Nicole and I was determined to marry her:

“You shall be a crown of beauty in the hand of the LORD,

and a royal diadem in the hand of your God.

You shall no more be termed Forsaken,

and your land shall no more be termed Desolate;

but you shall be called My Delight Is in Her,

and your land Married;

for the LORD delights in you,

and your land shall be married.

For as a young man marries a young woman,

so shall your builder marry you,

and as the bridegroom rejoices over the bride,

so shall your God rejoice over you.”

(Isaiah Chapter 62)

In her letter to me from Korea on June 9th, Nicole had asked me if I had a summer job yet. As a matter of fact, working as a summer intern at the august law firm of Wyman, Bautzer, Rothman, Kuchel and Silbert in glittering Century City, right next to Beverly Hills.

Nicole continued,

“I’m sure you’ve found out that being home again after college is stifling. Although if I remember correctly, you felt that way in 9th grade . . . . I used to love the feeling of walls around me, of my parents being close & knowing everything. The month before I left to college I remember thinking, “But I’m not ready, I’m not grown up enough.” Maybe I’ve just traded family walls for college walls.”

Then she wrote, “I haven’t forgotten to xerox that letter in which you called me Natalie. I can’t find it. Which one of us has the convenient memory?”

As a matter of fact, I didn’t know anyone named Natalie—and would certainly never have called Nicole, the love of my soul, by the name of another woman. Nicole apparently projected her own awareness that she was sleeping with others now onto an indecipherable patch of my handwriting.

Then, perhaps sensitive to the possibility I was deeply offended now that she was sexually active, Nicole continued the more forthright tone she had assumed in her letters to me since starting to have sex:

“My address in Vermont:

c/o Teela-Wooket Camp

Roxbury, VT 05669

“In the wild hope that you’ll visit the East Coast—the phone number is (802) 485-9891.

“Have a good summer, Chris. I wish I could take you up on your offer to see LA. But I’ll be leaving Seoul the 16th & I have to be at at the camp on the 17th. Next time?

Take care,

Nicole”

Nicole in Seoul - June 1980

As a matter of fact, events were about to take an unexpected turn. Henry Miller had died two days before Nicole wrote that letter, and I was about to drive to Book Soup in West Hollywood and buy Tropic of Cancer. My Onkel Christof was a German diplomat and was about to be transferred to New York City. Just as my father’s new assignment in Germany blighted the chances Nicole and I had to really get to know each other, my Onkel’s assignment created an unexpected opportunity to see Nicole.

My mother proposed I take a year off and move to New York City in order to get to know my uncle, who was her beloved brother. I suggested applying to Columbia University, where my father had studied Nuclear Engineering. My parents agreed. I applied and before long Columbia’s admissions department wrote me I had been accepted. I’d applied late in the summer and there wasn’t time to admit me for the autumn semester, so I would enroll at Columbia for the spring semester in January 1981.

Nicole and I would soon be 160 miles away from one another. After spending most of our high school years on opposite sides of the earth, and our first two years in college on opposite coasts of the United States, it would be the closest Nicole and I had been, except for a few hours in San Francisco, since I left Seoul in the summer of 1975.

And, again, you leave us on the edge of our seat! What a unique combination of the promise and torment of young love - particularly at a distance - along with Biblical interpretation. I, too, very much appreciate your honesty and insight of you as a young man finding your way. I am looking forward to your next installment.

Thanks so much for this Chris. I liked it a great deal and found what you had to say not only compelling but also honest. Just one observation - if I may. One of the themes in this and your preceding piece has been (as I understand it) attitudes towards the naked human body and, with growing maturity, the lack of shame we should feel for seeing it on display. In another sense, there is a second form of nakedness on display here - namely, you have exposed yourself to your readers. And that is what makes it compelling and honest to me.