Imminent Death

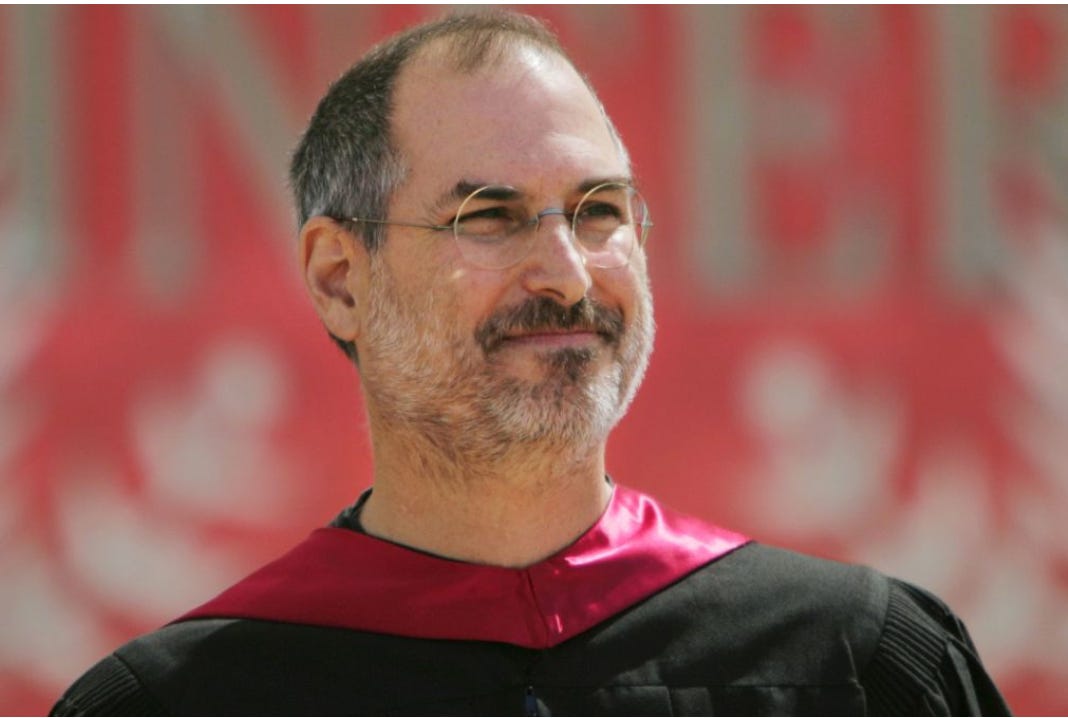

Steve Jobs gave a famous commencement speech at Stanford about eighteen years ago, in which he told the young graduates “Death is very likely the single best invention of Life.”

Steve had just recovered, he thought, from pancreatic cancer. In his speech, Steve described the shock of being told he almost certainly had incurable pancreatic cancer:

“It means to try to tell your kids everything you thought you'd have the next 10 years to tell them in just a few months. It means to make sure everything is buttoned up so that it will be as easy as possible for your family. It means to say your goodbyes.”

In Steve’s case, his mind was filled with these thoughts hour after hour for one long day. At the end of that long terrible day, Steve’s doctors performed a biopsy and discovered his cancer was a rare one that was completely curable.

So Steve received a reprieve and, as he noted in his speech, “I had the surgery and I'm fine now. This was the closest I've been to facing death, and I hope it’s the closest I get for a few more decades.”

In his speech Steve told the Stanford audience “three stories from my life”. They were about death, love, and what Steve called “connecting the dots”.

Steve’s brush with death confirmed he was right when, as a teenager in the 1960s, he made death the motivating principle for his life:

“Since then, for the past thirty-three years, I have looked in the mirror every morning and asked myself: ‘If today were the last day of my life, would I want to do what I am about to do today?’ . . . . Remembering that I'll be dead soon is the most important tool I've ever encountered to help me make the big choices in life.”

Steve gave a couple reasons for describing death this way. First, he said,

“Remembering that you are going to die is the best way I know to avoid the trap of thinking you have something to lose. You are already naked. There is no reason not to follow your heart.”

Secondly Steve said,

“Death is Life's change agent. It clears out the old to make way for the new. Right now the new is you, but someday not too long from now, you will gradually become the old and be cleared away.”

Steve was a master presenter, and Steve’s famous flair is obvious when you watch his speech. The Stanford audience laughed many times, but even in the glow of Steve’s charisma, I sensed he was wrong about death. I read the transcript and identified why Steve was wrong—and, to my surprise, I realized Steve knew he was wrong.

Love as a Distraction

Steve also told his audience in the same speech,

“You've got to find what you love. And that is as true for your work as it is for your lovers . . . . the only way to do great work is to love what you do . . . . Don't settle. As with all matters of the heart, you'll know when you find it. And, like any great relationship, it just gets better and better as the years roll on.”

This passage is at least as famous as Steve’s praise of death—but do both claims make sense in relation to one another? Why should you find what you love to do, or seek to have relationships with people whom you love, if you live in an indifferent universe that seems unaware of your presence between when you are born and when death comes, and you are “cleared away”?

If Steve Jobs is right about the way he describes death, love has no deeper meaning, loving reflects nothing about the underlying nature of reality. Steve trivializes love to nothing more than a distraction, the most absorbing way to occupy our time until we die. The great mathematician and philosopher Blaise Pascal, a greater genius than Steve and a devout French Catholic, wrote “If our condition were truly happy, we wouldn’t need to distract ourselves from it,” an insight that happens to be an epigraph to my second novel A Prince Among Men.

We can all agree the human condition isn’t consistently happy, and for many people it’s a misery. Most of us would admit that distracting ourselves from our lives is often a tempting option.

Is that all love is, just one of the options on the menu of ways to distract ourselves from reality? According to Steve, the essential nature of the universe is not loving, in fact the logic of the universe is murderous: it’s only a matter of time before it’s our turn to “be cleared away.”

Does Steve really mean it?

Seeing Positive and Negative Space

This publication is named Positive Space, and the concepts of “positive space” and “negative space” are art and painting terms. Positive space is the main part of a painting’s composition. Negative space is the rest of the painting and its area defines the relationships between the positive spaces in the painting. Positive and negative space together shape how we understand the meaning of what we see.

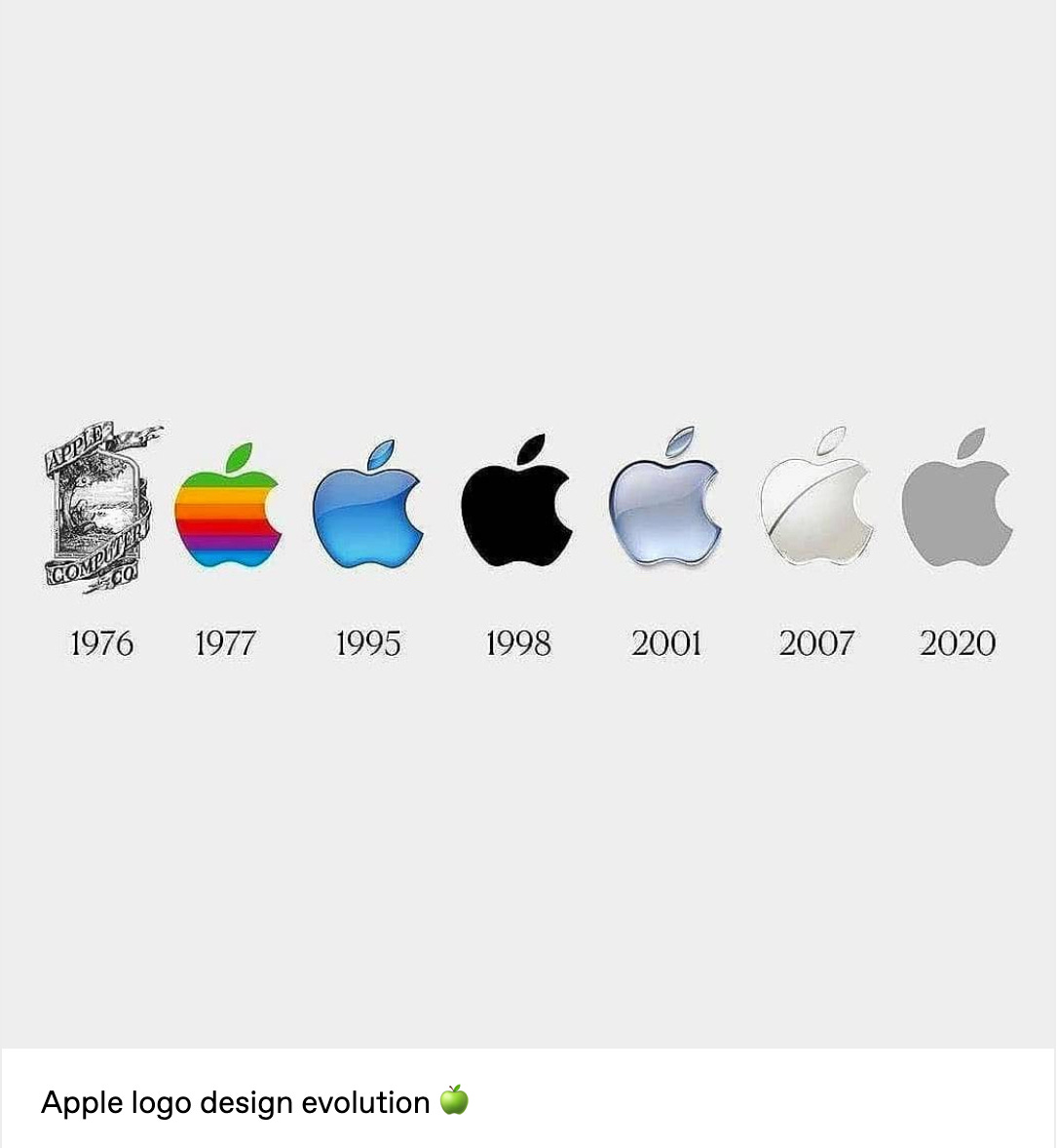

Steve was a master of aesthetics and design. He famously worked closely all his career with designers who developed the Apple logo and the company’s sleek, elegant products, beginning with Ronald Wayne, who co-founded Apple with Steve Jobs and Steve Wozniak, and some of the world’s most illustrious designers including Rob Janoff who developed the iconic logo, the great Jony Ive, and many influential designers including Imran Chaudri, Hartmut Esslinger, Robert Brunner, Kazuo Kawasaki, Christopher Stringer and Marc Newsome.

Source: https://www.tumblr.com/nr1-logo-design-inspiration/629312326875676672/apple-logo-design-evolution

Looking at negative space teaches us to ask questions: what is the relationship between positive space and negative space, and what is missing from the positive space? We know Steve understood the importance of negative space: the most important design element of Apple’s logo, the most valuable brand in the world, is the bite missing from the apple. Negative space.

Let’s see if we can understand Steve Jobs’ enthusiasm for the positive power of death by applying the concepts of positive and negative space.

Source: Kunsthistorisches Museum Wien

In this great painting, the positive space is black, quite “negative” in a certain sense, and the negative space is relatively lighter, and therefore, in a certain sense, more “positive”. But in art critical terms, the positive space has an overwhelmingly positive meaning because the figure in the positive space dominates the composition, signaling the importance of the individual in cosmic space.

This painting is, in fact, Rubens’ last self-portrait. The large proportion of positive space in the composition accentuates the many details showing this great artistic genius, a diplomat and seasoned man of affairs, a wealthy and accomplished man who has found his place in the world, well towards the top.

Connecting the Dots

Jobs used a visual metaphor in his speech to describe his early life, saying it’s “about connecting the dots.” It’s well known now that Steve was the child of two unmarried graduate students, Joanne Carole Schieble and Abdulfattah Jandali (Arabic: عبد الفتاح الجندلي) who met while studying at the University of Wisconsin. Joanne became pregnant, and she decided she would give up her baby for adoption as soon as possible after birth. A graduate student herself whose educational ambitions were thwarted by her pregnancy, Joanne’s one stipulation was that the adoptee parents be college graduates.

That’s not how it worked out.

Here is what Steve told his Stanford audience (and subsequently the world):

“Everything was all set for me to be adopted at birth by a lawyer and his wife. Except that when I popped out they decided at the last minute that they really wanted a girl. So my parents, who were on a waiting list, got a call in the middle of the night asking: ‘We have an unexpected baby boy; do you want him?’ They said: ‘Of course.’ My biological mother later found out that my mother had never graduated from college and that my father had never graduated from high school. She refused to sign the final adoption papers. She only relented a few months later when my parents promised that I would someday go to college.”

Abdul and Joanne in later years

An emergency middle-of-the-night birth, rejection and the initial refusal of life-giving hospitality. Then a child of destiny is raised by humble parents. Even the Eastern Mediterranean theme was reconstituted in the America of the 1950s: Steve’s German mother and Syrian father gave up their son to a German father and an Armenian mother, Paul and Clara Jobs.

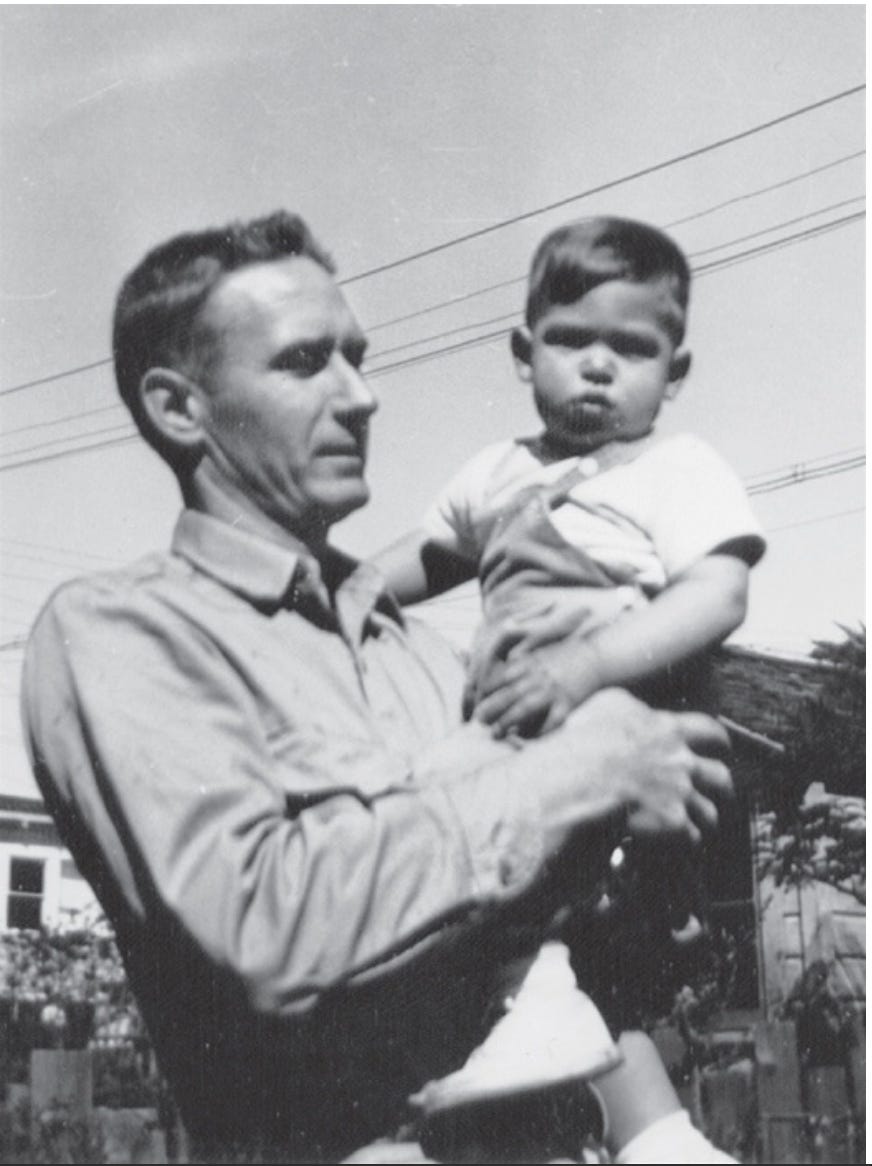

Paul Jobs and Steve

Source: https://allaboutstevejobs.com/bio/short_bio

Steve flourished in his loving home as his working class parents desperately scrimped and saved for his future college tuition. They stood by their word when he chose to attend ultra-expensive Reed College.

But within his first semester, Steve’s conscience asserted itself as he realized he was asking his loving parents to ruin themselves financially in order to better his prospects in life and keep their solemn promise to Steve’s biological mother Joanne. He decided to release them from their promise—as only he could—and he dropped out of Reed College:

“After six months, I couldn't see the value in it. I had no idea what I wanted to do with my life and no idea how college was going to help me figure it out. And here I was spending all of the money my parents had saved their entire life. So I decided to drop out and trust that it would all work out OK. It was pretty scary at the time.”

Clara and Paul Jobs in later years

One of the shapes that emerged when Steve connected the dots was self-sacrificial love: the willingness of his adoptive parents to destroy their financial future to keep their promise to their beloved son, and Steve’s decision to match the love of his parents by ensuring their financial security, even at the cost of putting his own future at risk.

Steve had to create negative space in his life in order for new positive spaces to emerge. He had to kill one version of his future, clear it away, in order for new futures to take shape within this emptiness. The Heart Sutra declares “Form is emptiness, emptiness is form” and even before Steve converted from being a Lutheran to Buddhism he seems to have understood it.

Joanne’s desperate, loving reliance on credentials to ensure her baby a good start in life was superseded by her teenage son’s decision to place his trust in the goodness and order of the universe. He was connecting the dots his way and shaping what turned out to be an extraordinarily consequential, special life.

At first, Steve’s act of loyalty and love seemed to doom his future. He had to stay alive by sleeping on friends’ floors, eating free meals at the Hare Krishna temple, and collecting empty bottles from trash cans in order to earn the five cent deposit.

There were other dots, too: Steve realized he was now free to audit courses at Reed College, choosing solely on the basis of what appealed to his curiosity and desire for knowledge. He couldn’t earn any credits towards a degree, but they were free.

Paul Jobs, Steve’s loving German father, was a machinist who enjoyed spending his weekends tinkering with electronics in a lab / work room he set up in his garage. It would become the second most famous garage in the world, after David Packard’s garage. Steve’s biological father was a political science professor who later ran a restaurant in the U.S. It’s hard to see how Steve would have benefited from either his biological father’s expertise or that of the lawyer who rejected Steve for not being a girl.

“You can't connect the dots looking forward; you can only connect them looking backwards,” Steve told his audience. “So you have to trust that the dots will somehow connect in your future.”

Steve was often hungry between meals with the Hare Krishnas, but he was finding nourishing inspiration that stimulated his creativity from classes he took without any practical motive. One of those classes was calligraphy, which shaped the way Apple computers, (and through the relentless imitation of Microsoft, all computers), were eventually designed. Was it partly Steve’s Arab genetics, with centuries of exposure to the aesthetically beautiful, flowing, Arab script that made calligraphy so appealing?

Bill Gates borrowed $50,000 from his corporate lawyer father to buy the rights to MS-DOS, the start of Microsoft. Working class Steve Jobs moved back home after eighteen months and obtained his parent’s permission to set up in his father’s garage workshop with the technical genius Steve Wozniak.

When Steve gave his Stanford commencement speech on 12 June 2005 he had come a long way from the young man who incorporated Apple Computer on 1 April,1976. But the shape of his life emerging in 1976 from the way Steve connected the dots was already a composition recognizably similar to the Rubens self-portrait at the High Renaissance, the apogee of the dignity and value of the individual in Western Civilization. In 1980, Apple became a publicly listed company with a value of $1.8 Billion and Wozniak’s Apple I and Apple II computers revolutionized the brand new market for personal computers. The Renaissance understanding of the ability of the individual to make a consequential difference in the world is echoed in Steve’s famous challenge to John Sculley, which convinced the top Pepsico executive to join Apple: "Do you want to sell sugared water for the rest of your life? Or do you want to come with me and change the world?"

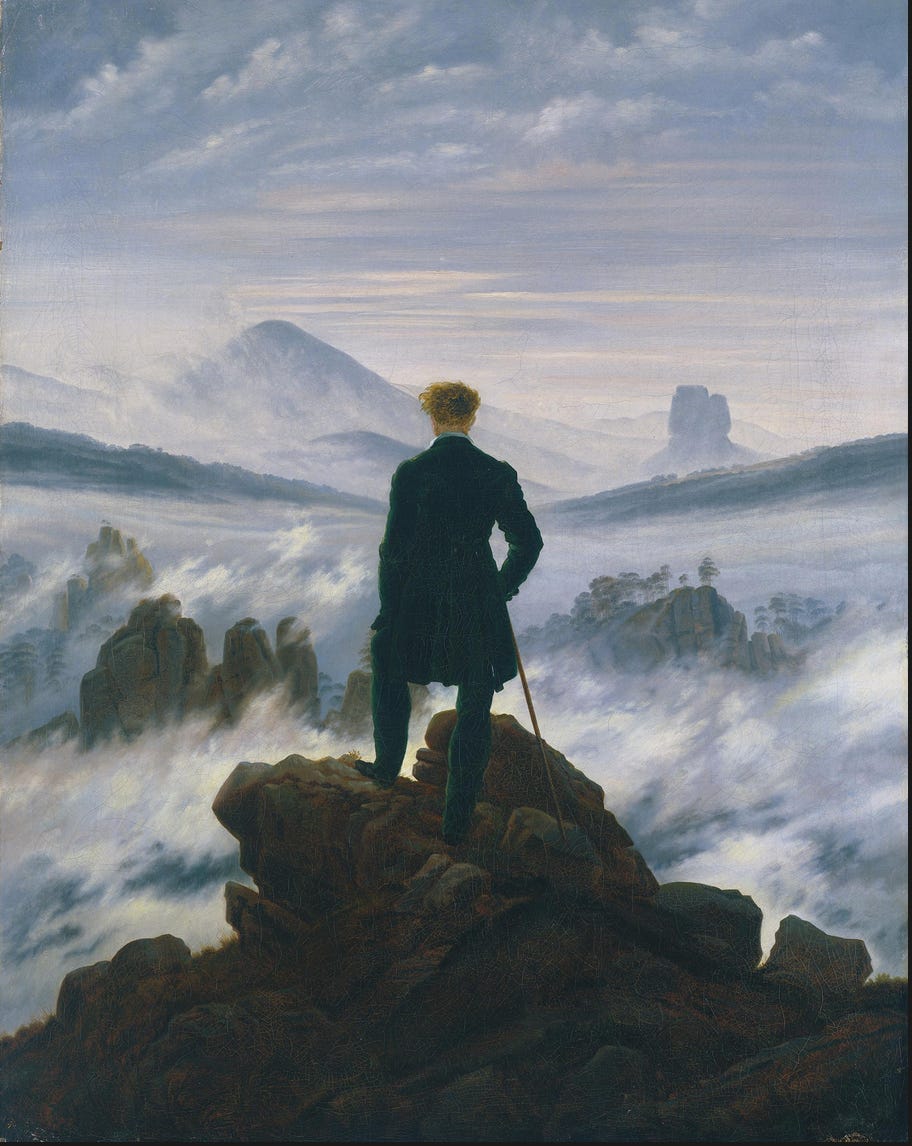

The Wanderer

Source: Hamburger Musee Caspar David Friedrichs 1814

This painting is another example in which the positive space could be conventionally considered “negative” because the figure of the man and the rock he’s standing on are quite dark. The negative space is arguably quite positive in that it is light and welcoming. In addition, the positive space is much smaller than the Rubens self-portrait and positioned in the lower portion or the painting, which in the visual hierarchy could be interpreted to reduce the value of the man standing on the overlook relative to the importance of the individual expressed in the late Renaissance Rubens painting.

In fact, most of us would agree that this influential painting called “The Wanderer above the Sea of Fog” is quite an inspiring image. The negative space visually reads as a transcendent realm of knowledge and hopeful developments, and the confident bearing of the man and his authoritative leg positioned at the apogee of the rock suggests not just a physical adventurer, but an intellectual adventurer who has made the arduous climb above the now-dissipating realm of ignorance and superstition into a bright and seemingly limitless sphere of objective knowledge and scientific progress. It was painted in 1814 by the German Caspar David Friedrichs and reflects this hopeful understanding of the Enlightenment era.

By 1814 the role of humanity was diminished considerably from the High Renaissance of Rubens’ career because of the new understanding of the heliocentric universe and its enormous size, the discovery of North and South America and Australia, which radically increased understanding of the scale and complexity of both geography and the diversity of human culture, and a certain humility, even despair, produced by the ultra-violent European Wars of Religion (including the infamous Inquisition) that were the culminating act of the Renaissance. The Enlightenment was a time of great hope, confidence and even arrogance that by focusing the human intellect on intractable traditional problems a new sense of rationality, new technologies, and new institutions such as elected governments could produce transformative benefits for all.

This was how the painting was widely interpreted in its day at any rate–as a visual expression of the battle cry with which Kant inaugurated the Enlightenment a generation before “Aude Sapere! Dare to Know!”

Steve hired John Sculley in 1983, and almost immediately began to clash with his new CEO. IBM and Microsoft had teamed up to compete against Apple, and Steve’s goal was to respond with a computer overwhelmingly better than the best-selling IBM PC and its clones. But Steve’s interference with the engineers and designers of the LISA computer was so disruptive he was kicked off the development team and he focused instead on a new computer designed to be as easy to use as a toaster, the Macintosh.

Like The Wanderer, Steve’s mind was full of big ideas. He was determined to oust his new CEO John Sculley. He was sworn to crushing the powerful alliance of IBM and Microsoft, and he memorably launched the Macintosh computer with an unforgettable Super Bowl advertisement that made huge political, social and cultural claims for the importance of the simple little computer:

Apple 1984 Orwell Ad

The conflict at the top of Apple resulted in Wozniak leaving the company, Steve attempting a boardroom coup against John Sculley—and finding himself ousted instead. He left the company on 16 September, 1985.

Steve spoke frankly about how “devastated” he was to be fired from Apple, how he imagined himself as having failed in some way as the inheritor of the Silicon Valley legacy, and how he tried to apologize to the owners of the most famous garage in the world, David Packard and Bill Hewlett. During this period, Steve said he felt so publicly humiliated he even considered leaving Silicon Valley and the computer industry.

According to Steve, since he was seventeen he’d been making big decisions by looking himself in the mirror and reminding himself he’d be dead one day. Did Death inspire him to do what he did next?

Well, no . . . not according to Steve:

“Something slowly began to dawn on me — I still loved what I did. The turn of events at Apple had not changed that one bit. I had been rejected, but I was still in love. And so I decided to start over.”

It soon became clear to Steve that the creative power of love transformed the humiliation of his abrupt firing into one of the most wonderful periods of his life. Clearing away didn’t only end something, it made possible something much better. He didn’t choose to leave Apple the way he had voluntarily quit Reed College, but opening up negative space again allowed Steve to create unprecedented and wonderful positive space:

“It turned out that getting fired from Apple was the best thing that could have ever happened to me. The heaviness of being successful was replaced by the lightness of being a beginner again, less sure about everything. It freed me to enter one of the most creative periods of my life. During the next five years, I started a company named NeXT, another company named Pixar, and fell in love with an amazing woman who would become my wife. Pixar went on to create the world’s first computer animated feature film, Toy Story, and is now the most successful animation studio in the world. In a remarkable turn of events, Apple bought NeXT, I returned to Apple, and the technology we developed at NeXT is at the heart of Apple's current renaissance.”

While I was writing this essay, I noticed the appearance of what seems to be a skin cancer similar to one I had several years ago. I’m not particularly worried: last time, a forty five minute procedure and half a dozen stitches removed the basal cell carcinoma.

But this reminder of my death, whenever it may be, did nothing for my creativity as I wrote this essay. In fact, only by parking the possibility that I have a life-threatening cancer, and choosing to focus on this essay, have I succeeded in completing it. So I don’t buy Steve’s assertion he was motivated by his awareness of death—and Steve agrees with me: it was remembering the role of love in his life that got him through the biggest crisis of his career, and transformed him into the man who created Pixar and introduced the iMac, the iPad and the iPhone.

Love, not death.

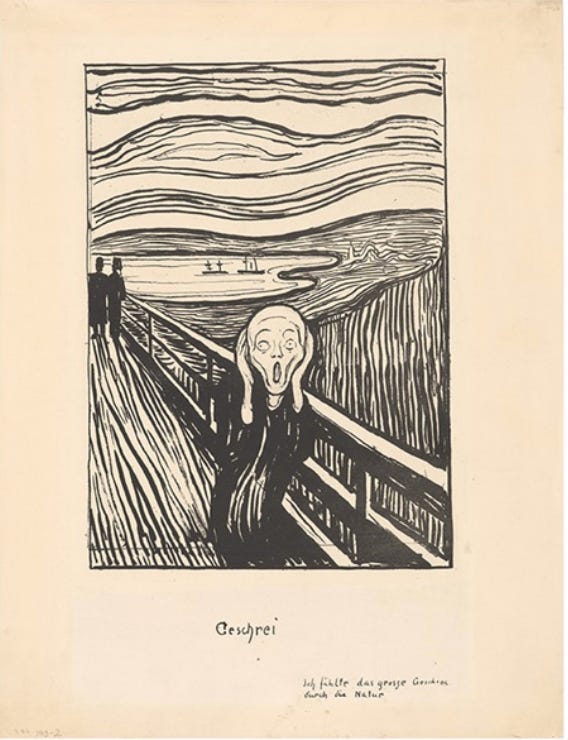

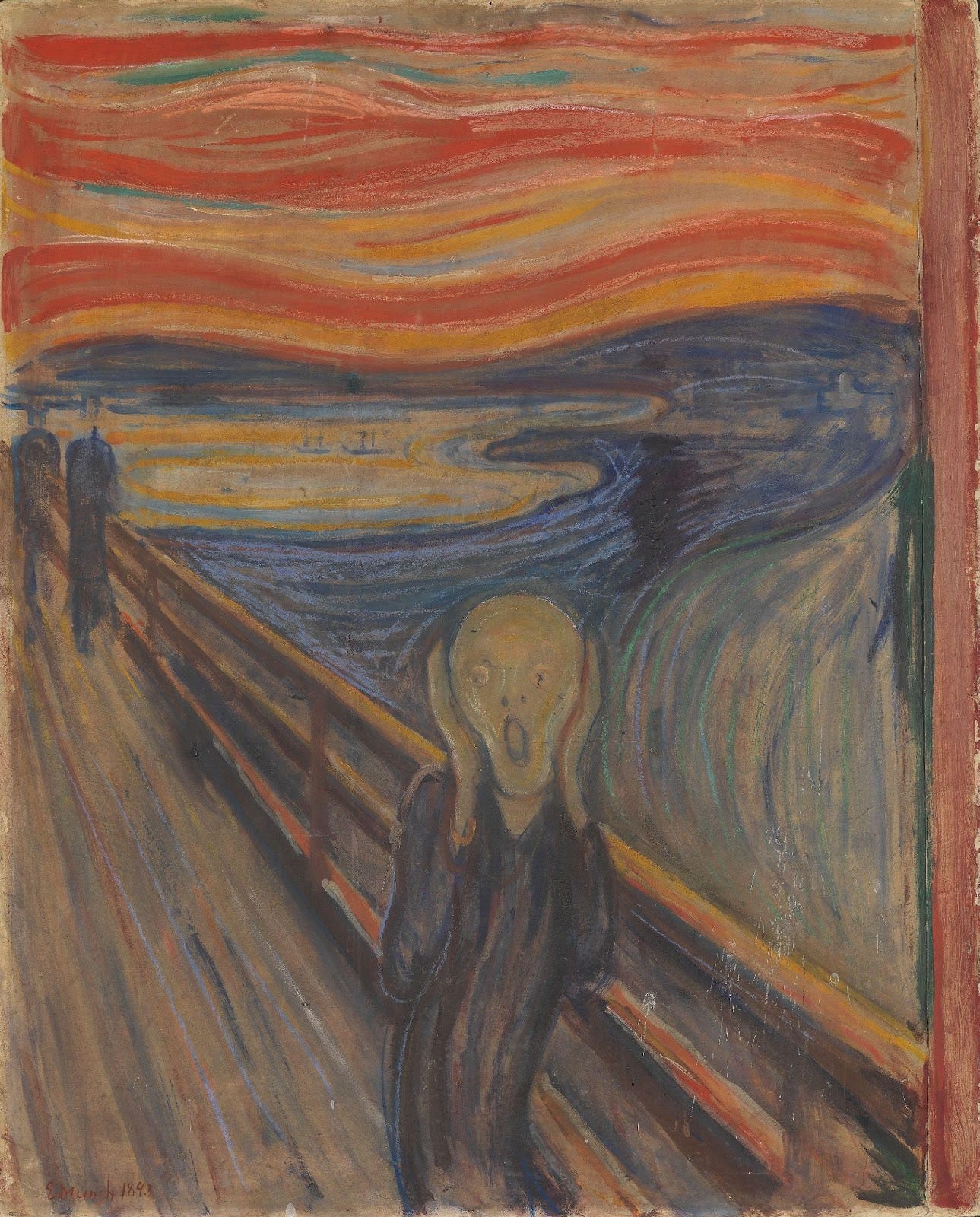

The Scream

Lithograph (1895) © A. Liebmann Buch u. Steindruckerei

This is “the most famous motif of the Twentieth century”, Edvard Munch’s “Geschrei” (The Scream). Munch wrote about the occasion that inspired it:

“I was walking along the road with two friends . . . Suddenly the sky turned blood-red – and I felt a breath of melancholy – an exhausting pain . . . and I felt that a great infinite scream went through nature.”

The image we see most commonly today is a synthesized version made up of this lithograph with colour added by contemporary artists in a variety of ways. That’s reasonable, because Munch himself created alternative versions, and it’s interesting to observe the changing relationships between the positive and negative spaces in the various compositions.

The lithograph was done in 1895, two years after the original tempura and oil paintings, and we can see that arguably there is very little negative space at all in this composition in which the individual has shrunken and descended even further down the visual hierarchy to the bottom of the composition. Perhaps narrow bands of the sky and the lake could be considered negative space.

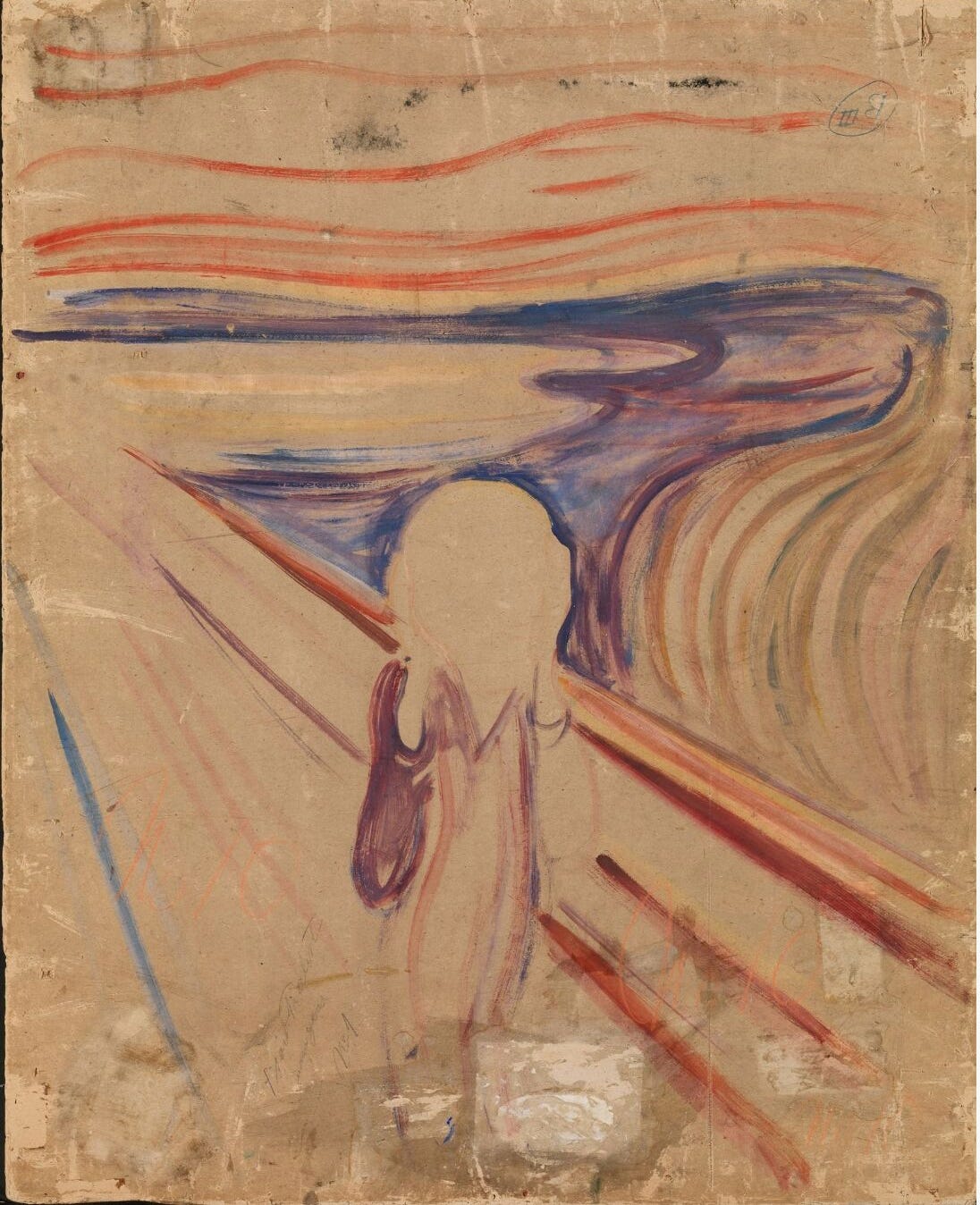

In the original drawing below, the composition is almost all negative space. The whiteness is not the luminous realm of ideas and hope as it is in The Wanderer.

Original drawing: (1893) Source: National Museum of Norway, Free use (Creative Commons - Attribution CC-BY).

It’s impossible, of course, for us to “unsee” the famous horror-stricken face in the completed painting, so perhaps it’s merely projection to see in this original drawing of white empty negative space a horrible, sterile emptiness. But we instinctively understand the negativity emanating from the enigmatic positive space limned by the skull shape.

In the tempura painting below, created in the same year as the original drawing above, Munch darkened the sky to the “blood red”, bridge and lake arguably intermingling the negative space until the entire composition is positive space–but a horrible positive space. The complete image vibrates, resonates with, and amplifies the scream emanating from the curiously diminutive oval of the figure’s mouth. This expresses what Munch writes about the moment he seemed to hear “a great infinite scream go through nature.”

Original tempura and oil on cardboard: (also 1893) Source: National Museum of Norway, Free use (Creative Commons - Attribution CC-BY).

The hierarchy of space: Steve’s three stories about connecting the dots, finding what you love, and death are like the three levels of hierarchy in those paintings, whereby the human gets smaller and smaller, and lower and lower, and is finally reduced to the scream. The negative space and positive space merge: there is no negative space. The entire meaning of the composition is the all-encompassing horror with which everything is vibrating. Every atom of nature choruses together in one soundless scream of horror and fear.

It was during the Renaissance that humanity began to realize how enormous the universe really is, and how physically insignificant we are by comparison. But in an age that still believed in the dignity and consequentialness of being human, Pascal wrote this famous insight: “Man is only a reed, the weakest in nature, but he is a thinking reed . . . even if the universe were to crush him, man would still be nobler than his slayer, because he knows he is dying and the advantage the universe has over him. The universe knows none of this.” For Munch, any notion of nobility has drained away, there is no noble distinction between inanimate nature and a conscious human being, and consciousness is suffused with anxiety and horror.

We can’t connect dots in advance. When Steve described the dots of his past in his commencement speech and then connected them, he gradually shifted his focus to the negative space in the image they produced, without explaining how clearing away one set of possible futures produces negative space which makes possible a wonderful new future. Instead, he effectively tells us he too can hear all nature scream with the consciousness of death.

Negative space shapes the relationships between the positive elements of a composition. Steve waited until after his adoptive mother Carol died of lung cancer before reaching out to meet his biological mother Joanne. Death influenced the timing of Steve’s decision, but the positive spaces were shaped by his love and loyalty to Carol, and ultimately his love for Joanne. Death was only the negative space in Steve’s reunion with Joanne, the emptiness that made possible the positive space in which love connected mother and son.

Similarly, it seems absurd to explain Steve’s decision not to spend his parents’ life savings on his college education by attributing it to his awareness of death. It’s clear from his own account Steve’s decision was actually inspired by love, which in turn generated the courage for Steve to trust an unknown world with his future.

Steve, Death and Me

The apparent return of my skin cancer in the past few days reminded me Steve and I have something important in common: a vulnerable pancreas.

Just before I turned twenty nine—the same age at which Steve was about to IPO Apple for over a billion dollars—I almost died of a severe attack of pancreatitis after twelve hours of agonizing pain. When the attack began, it felt like someone had placed the muzzle of a .357 Magnum against my sternum and pulled the trigger, leaving my insides completely shattered and torn apart, and yet I was somehow still alive. Women who have had pancreatitis say it’s as bad or worse than child birth, and my amylase and lipase enzyme levels were 840—almost off the chart. It was the most excruciating agony I've ever experienced, and I’m someone who has been shot and had various accidents.

Photo 23506302 / Hospital Iv © Aviahuismanphotography | Dreamstime.com

Afterwards I lay in the Charing Cross hospital in London with an IV in my arm, waiting for my digestive system to start. Pancreatitis essentially creates a toxic waste dump in your body which shocks your digestive organs into paralysis. There’s nothing that can be done except to keep you hydrated. If your body resumes functioning, you live. If not, you die.

What did I learn from my near-death experience?

I did not learn the value Steve ascribes to knowing that one day you’ll be dead, nor did I learn anything like his claim that death is the greatest invention of life.

Think about it: if you take literally Steve’s advice to practice living as if each day is your last, you’d have to be some kind of unemotional robot to go to work developing an Apple computer on the last day of your life. A normal, healthy person would be spending time with his family, loved ones, and friends—and reaching out to the ones he couldn’t see before he died. You can't actually live each day as if it’s your last—you don't get on with your life. So that part of Steve’s advice is actually irrelevant and meaningless. Steve knows it, too. When he talked about getting the initial diagnosis of pancreatic cancer and being told he needed to go home and put his affairs in order because he was almost certainly going to die soon, like my friend Marcus it was about life and love he thought first, the lives of his wife and children, and how much he loved them.

I was single at the time I almost died, but the strategy I found most helpful was to ignore the strong possibility that at any moment I could suddenly begin dying in agony. Far from looking myself in the mirror every morning and reminding myself one day I would be dead, I got on with marrying, raising three children, and building a career as an investment banker and then an entrepreneur.

For all those decades, I knew that at any moment, whether I was at work, or on a vacation, playing with my children, or looking after them when they were sick at night, or whatever it was, the pancreatitis could suddenly start again and I would suffer hours of agony, and then death. I actually did have another pancreatitis attack eleven years later when I had three children, but fortunately it was mild.

I didn't hesitate to live as if I was going to see all my children grow up to be adults, which they have done, and to see all my projects, and all my relationships, to maturity. I wrote two novels, one of which took me nineteen years to publish. I started it two years before Steve’s Commencement speech, and if I had taken Steve’s advice, I wouldn’t have done it. If I were motivated by death, assuming I wasn’t totally crushed by despair, depression and fear, I would have just written brief daily essays or short stories that I could complete in one sitting in case I died at the end of the day. In fact, I did the opposite: I embarked on huge, long term projects nobody would have ever seen if I had died before they were completed.

Proclaiming that “death is the most important tool of life” confuses negative space with positive space and fuses the two into a nightmarish composition like Munch’s painting. Steve connected the dots of his life and claimed it was all just a scream.

The truth, as Steve himself knew, was very different. He said it himself:

“Don't lose faith. I'm convinced that the only thing that kept me going was that I loved what I did. You've got to find what you love. And that is as true for your work as it is for your lovers. Your work is going to fill a large part of your life, and the only way to be truly satisfied is to do what you believe is great work. And the only way to do great work is to love what you do. If you haven't found it yet, keep looking. Don't settle. As with all matters of the heart, you'll know when you find it. And, like any great relationship, it just gets better and better as the years roll on. So keep looking until you find it. Don't settle.”

The Song of Solomon tells us “Love is as strong as death.” Love is our priority. Steve knew it, too: when he’s describing the gorgeous positive spaces in his life, he uses the words trust, faith and love.

It’s not death, but love that shows us what to do each day. Love nurtures the trust and hope we need to do what our hearts desire, to express ourselves authentically, and to leave the world a better place than when we arrived, “and hope does not disappoint us (Romans 5:5).”

Take it from Steve and me.

Links

Here's the link to the transcript of Steve Job’s speech: https://news.stanford.edu/2005/06/12/youve-got-find-love-jobs-says/

A link to a YouTube video of the speech:

Link to article about Apple logo: https://www.vectornator.io/blog/apple-logo/

Link to Kunsthistorisches Museum: https://www.khm.at/en

Link to Hamburg Art Museum: https://www.hamburger-kunsthalle.de/en/nineteenth-century

Link to Munch Museum: https://www.munchmuseet.no/en/

Link to British Museum discussion of Munch and The Scream: https://www.britishmuseum.org/blog/10-things-you-may-not-know-about-scream

Link to National Museum of Norway: https://www.nasjonalmuseet.no/en/collection/object/NG.K_H.A.18995

Such a wonderful, thought-provoking piece! I really enjoyed how you worked in your personal experiences around facing possible death along with Steve's nuanced journey. Bravo.

Fascinating essay, Chris. So interesting your parallels between Steve, negative/positive space, and your own experience. It indeed is love, not death, the greatest invention of mankind. This is a massive piece, full of precious references and brilliant ideas. And your personal story, and what happened to you, is truly inspirational. It says 24min reading on top, but I took my time and went much slower, as this piece deserves. Thank you for writing this. I sense I will return to it over and over again.