On this day twenty-five years ago my father died. My brother woke me up at 4:20AM in the hotel in Adelaide, Australia were I was staying on a business trip. At first I couldn’t make sense of what Steve was saying, because even in the grogginess induced by a big client dinner that had ended only several hours before, I knew it was absurdly improbable that my father was dead; he was 68 and seemed to be in decent health. But my brother’s serious tone in response to my protests of shocked disbelief quickly convinced me the absurd was true. At that point, there were few details about what had happened, so we had a brief, business-like conversation, I told my brother I would get to Los Angeles as soon as possible, and we said goodbye.

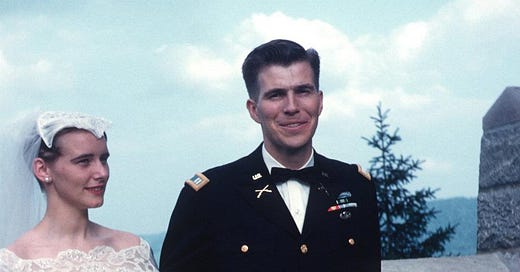

Dad and Mom on their wedding day, West Point, 30 May 1959

Dad had died a couple hours earlier on the morning of November 17th in Los Angeles, a Tuesday. But in Adelaide it was already Wednesday, November 18th, the day after Dad died. That seemed to refute the terrible immediacy of my loss, but my shock and pain told me the truth. As I woke up and the reality my father had just died began to sink in, the walls of my spacious hotel room seemed to close in on me and I became restless.

I’d been living in Sydney for three years by then and I already knew Adelaide well after numerous business trips, so I thought of the pleasant park and the running / bicycling path that ran along the sluggish Torrens River right behind my hotel. It was late spring / early summer in Australia and Adelaide is on the country’s southern tip so I knew the sun would rise before long. I hurriedly dressed in the clothes I’d worn yesterday—crumpled white shirt, business suit, English leather shoes, carelessly knotted my necktie—and, after walking to the riverside path, I called my sister in Paris.

Cindy already knew Dad had died, and she was bereft.

Unlike my brief conversation with my brother, Cindy and I had a long, emotional, wide-ranging conversation as I walked in the darkness beside the river; she was going to have to fly almost as far as I would to attend Dad’s funeral.

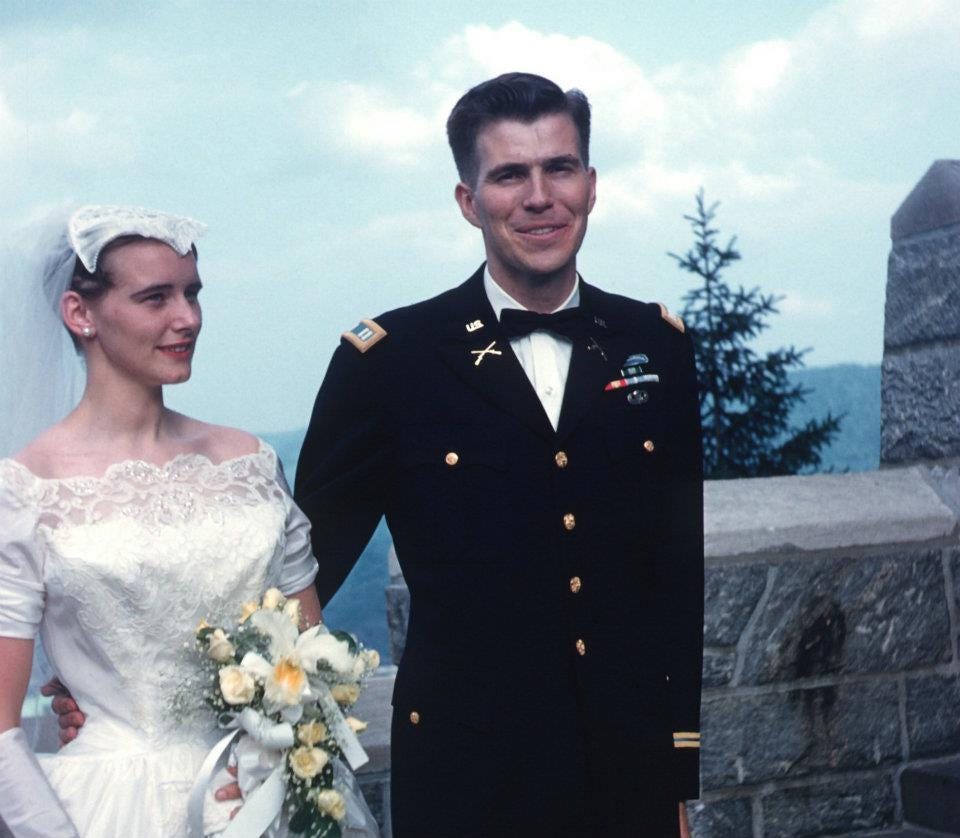

Dad teaching chemistry at West Point, Early 1960s, my brother Steve and I were born during this time

At first I was completely alone on the path, but as the gloom began to lift, joggers and bicyclists appeared and began passing in both directions. I paid no attention as I continued to talk with my sister, both of us in shock.

Suddenly Cindy told me she felt enveloped by the warm, loving presence of our father coming to comfort her and say goodbye. A few moments later, I had the same sensation, and I still remember it as an almost sparkling swirl of warmth and light all around me, like the way those old, great Disney films used to depict the arrival of a good fairy. Dad’s presence had left Cindy by now, and it was I who felt the same warmth and love, and the joyous presence of my father comforting me, saying he was perfectly fine, and goodbye.

This welcome and consoling experience was surprising to me, not on account of some paranormal, metaphysical consideration—it was so palpable and matter of factly real to me—but because my father and I had last had a good relationship when I was about eleven years old. When I was a boy, he was a good dad. Dad was an Eagle scout and taught me how to backpack, hike and camp, how to ride a bike and whittle with a pocket knife, and how to shoot safely and accurately. He’d also set me an example of matter-of-fact courage as a battalion commander during the most violent fighting in the Vietnam War.

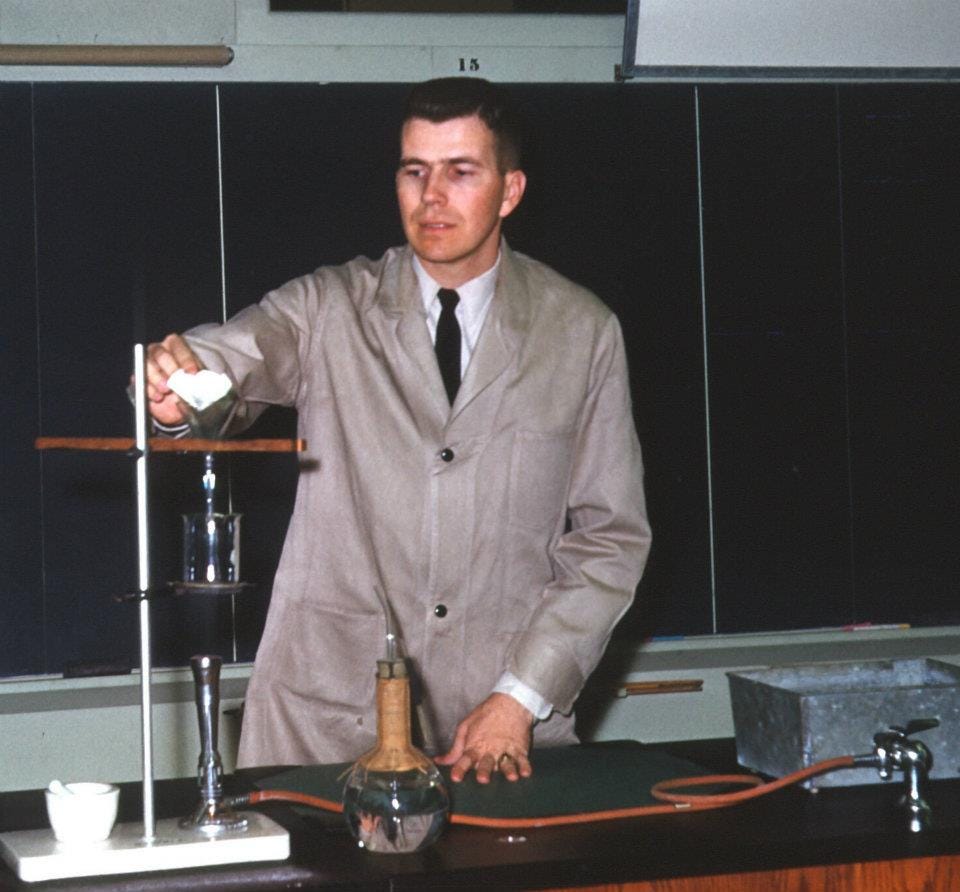

Mount Rushmore, South Dakota, a cold day in the summer of 1968 after Dad returned from Vietnam

Yet he also blocked me at every turn as my personal interests and passions emerged. I learned the word “plagiarism” at the age of ten after showing him the first chapter of a book I started to write; when Dad returned the pages he told me not to claim someone else’s work as my own. Doing so, he told me severely, was a form of lying called plagiarism. It actually was the first clear appearance of my genuine writer’s voice, but Dad refused to believe it. He didn’t want me to be a writer, and he never would.

Dad wanted me to go to law school, become a lawyer, enter politics and become a great leader. All through my teenage years Dad’s exhortations were an early version of Personal Improvement Twitter: he woke me up every day on his way to work by opening my bedroom door and saying, “Rise and shine—this is another day in which to excel!” But I had different ideas about how I wanted to excel, and as I chose my own course in life, my father and I grew increasingly distant.

That was why the sudden, intensely personal and loving connection with my father as I walked beside the Torrens River in the Australian dawn, and hearing my father somewhere in my mind or soul speaking wisely and consoling to me, was an utterly unexpected return to the best moments of my childhood.

Søren Kierkegaard lives on into our Internet age mostly because of one thing he wrote that has ubiquitously seeded social media: “Life can only be understood backwards; but it must be lived forward.” The morning my father died, I was 38 years old and living a life that was ironically a mirror of his original model for me (although neither he nor I had been able to see it while he was alive): not law, but investment banking, not politics but the highly political market of energy and infrastructure. The life I was living forward was full of hard work to support an extravagant life style for my family and ascend the rungs of status and power in Sydney.

I must have been walking unsteadily and erratically by now, because I was intentionally buzzed very close by several bicyclists who cursed me as they passed. My awareness gradually shifted from my own consciousness to the brightness of a sunny Australian dawn and the warmth of the rising sun.

I realized that in my expensive but crumpled clothes—clearly yesterday’s—unshaven, talking intently on my mobile and walking unsteadily, I must look like someone trying to organize a taxi (there were no Ubers then) or convince a friend to pick me up. The Adelaide Casino was nearby, and to the health-conscious, disciplined joggers and cyclists, I looked like somebody who was hung over and had gambled away all his money the night before or been robbed by a hooker—or both. I was an object of contempt and judgment.

Arrival at Kimpo Airport, Seoul Korea, August 1973, Dad was one of the youngest Colonels in the US Army, and he was assuming command of the Yongsan Garrison, the largest Colonel’s assignment in the world

I didn’t mind. In fact, I understood their perspective. I was full of love and comfort.

I had been awoken into an emptier world, to a grave loss and the final termination of any possibility of reconciliation and true appreciation between my father and me—but I had just felt his presence, and we’d connected more authentically than we had ever done since I became a man.

I was going to have to cancel the rest of my business trip, return home to Sydney and organize the flight to LA, and leave my wife with our seven, five, and one year old children. On that morning in late November 1998 the Asian Financial Crisis was skidding into disaster, but I was determined to attend my father’s funeral.

Despite my pain and shock from the loss of my father, and the growing chaos in the financial markets, I was aware that morning of an underlying harmony in the world, a deep order that connected brothers and a sister in Australia, America and France, and the three of us with our father as he transcended our common consciousness for a higher one. I suddenly saw that loss can be only apparent, and may in fact enrich a failed relationship that had succumbed to the limitations of this earthly life.

When I returned to Los Angeles days several days later and learned more about the circumstances of my father’s death, I started to understand what Jesus meant when he said, “Let the dead bury the dead” and “God is not the God of the dead but of the living.” I did fulfill those duties of the dead to the dead over the next several days, and then for the following year as I investigated and uncovered the true circumstances of my father’s death. But I understood that I was tidying up earthly matters, for whatever limited purpose that might have.

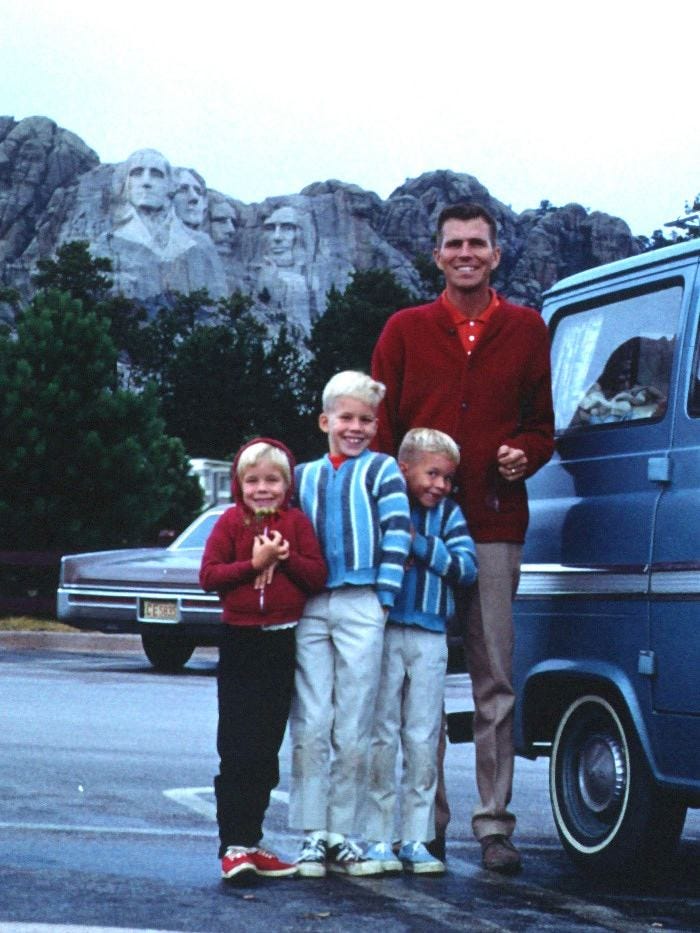

Dad with my second son Alex, about 1994, Dad was about as old as I am now; he and I have aged very differently.

The real order of life had been revealed to me by my father’s decision to bestow his loving presence on me as I walked beside the river. I have always understood since then that our actions in this life are like the finger pointing at the moon, not the moon itself, although earth and the heavens share overlapping fields of causality. I believe my father had finally attained a perspective far beyond and above those things in which he exhorted me to excel; those too were things of the dead, and now that he was truly alive, my Dad had been liberated to assist us with real life, and to nudge me and my brother and sister towards decisions about what really matters.

In a conversation after his funeral just before I left LA, while my sister and I were standing by my rental car before I drove to the airport, I told Cindy I was tired of seeing her pale, thin, and unhappy every time she left Paris, and then witnessing her blossom back to her real self, only to put her back on a plane to Paris knowing she would soon revert to her miserable state. I invited her to come down to Australia and spend a year with my family thinking through what she should do about her life and marriage in Paris.

Dad seemed to be telling me what to say, and telling Cindy to listen. She and my Dad had seen each other during the years she lived in Paris, but he had done nothing to alter the sad status quo of my sister’s life. Now that he was gone, Cindy and I suddenly saw her predicament with clarity, as if a new perspective had just been conferred on us. Since then, Cindy’s life—in Sydney, Haiti, Chad, Nigeria, Congo, Turkey, Jordan and now again in Sydney, living only a few hundred yards from where she first lived when she came to stay with us—seems to confirm our father guided and blessed her in some way.

I also experienced a subtle influence while investigating his sudden death. Once I had gathered all the facts available, I interviewed my father’s doctors, and unknowingly came within one person of rediscovering the lost love of my life, Nicole, who was now a doctor and one of the closest colleagues of Dr. Eliasson at Walter Reed Army Medical Center, who had cared for my father in the last years of his life.

I wouldn’t know for many years still that I was talking to one of Nicole’s colleagues, but I think Dad may have been responsible for my realization shortly afterwards that the figure at the center of the financial crisis that year was none other than Nicole’s younger brother. That discovery was a surprise that rocked me to my core, bringing memories flooding back that were no longer muted by the pain my father had been one of those most responsible for inflicting.

Those memories, now that I could bear them, turned out to be the opportunity for a profound reassessment of my life. It wasn’t so much that I understood my life backwards as that I had accessed a meta-perspective on my life. It revealed a harmony I hadn't noticed shimmering across the arc of my life, and convinced me to begin relinquishing my focus on the things of the dead. While for the time being, I made a recommitment to the course I had chosen, I also simultaneously set new coordinates for an entirely unexpected destination that would be revealed only many miles, and many years, later.

That was the occasion for writing, and the true subject of, my novel Crisis Deluxe.

I agree with you, and would add Pnin to the worthwhile works of his American period; it’s also perhaps uniquely sweet and tender.

Beginning with the game-changer Lolita, and very evident in The Real Life of Sebastian Knight and increasingly so in Ada and Transparent Things is a chthonic, even explicitly satanic, spirituality. I see no evidence of that in your work! You’re a classic Italian Catholic, world weary and uneasy but fundamentally at home even if you identify as a wayward son.

Also, Nabokov’s worldview and aesthetic was based on deception and the murderous threat concealed in the attractive and apparently nutritious lure. His collection of interviews “Strong Opinions” are a tissue of lies, interweaving falsehoods of both commission and omission.

Again, I see your work as expressing a delicate and persistent pursuit of the truth, not necessarily in a universal sense but as it can be located and authentically expressed within the context of your sensibility in response to your life experience.

Nabokov had no such commitment. He delighted in deeply transgressive epistemological acrobatics, most famously writing a novel about child abuse from the perspective of the abuser, and presenting HH as so charming, witty and lacrymously pseudo-penitent that readers are tempted to align with his twisted and exploitative perspective and sympathize with his—not Lolita’s!!!—plight.

Again, there is a vast gulf between your work and Nabokov’s.

This is beautiful, Chris. And very touching. Thank you for sharing these intimate memories. "I had been awoken into an emptier world, to a grave loss and the final termination of any possibility of reconciliation and true appreciation between my father and me—but I had just felt his presence, and we’d connected more authentically than we had ever done since I became a man." -- I was particularly moved by this paragraph. Your experience is indeed a testament to the profound human connection that transcends physical boundaries. A reminder that love and understanding often reach their purest form in the least obvious, non-terrain configurations. That deepest bonds endure beyond the constraints of time and distance, and matter.