“But who may abide the day of his coming? and who shall stand when he appeareth? for he is like a refiner's fire . . . And he shall sit as a refiner and purifier of silver: and he shall purify . . . and purge them as gold and silver, that they may offer unto the LORD an offering in righteousness.”

Malachi 3: 2- 3

Giga Deals

You don’t know somebody until you’ve been through a big deal together.

I mean, literally, a big deal: a large merger or acquisition.

Successfully completing a billion-dollar merger and acquisition (“M & A”) deal, a “Giga Deal”, can change your life. Of the tiny number of people who ever get to work on a transaction worth billions, many of them will do just about anything short of murder to win.

Even when an M & A professional isn’t driven to his or her dark side by the chronic stress of a Giga Deal, the forces converging on the deal eventually crush everybody, at one point or another, leaving them in broken fragments of themselves. Being in that state is very emotional, and it’s when the temperature rises . . .

Let’s say it’s 2AM local time, and you’ve been working with eight or nine people for eighteen hours, and it’s been like this for months. A call comes in from London: the news is bad. 17,000 kms away, the colleague says he’s just heard from Zurich and the tax structure the Swiss accountants have been negotiating won’t work. Suddenly, your client goes from looking like a winner to probably losing the deal.

Photo 116671502 | Office Buildings © Radub85 | Dreamstime.com

In a crisis like that, when everybody is already exhausted and emotionally over-stretched, all kinds of things can happen: screaming matches, fist fights, and more. At best, lawyers revert to being lawyers, bankers revert to being bankers, economists revert to being economists, tax accountants revert to being tax accountants—even if their area of expertise is totally irrelevant to finding a solution.

You, as the investment banker running the deal and managing the team on behalf of your client, must stay objective. Your job in the crisis, while everybody else is acting out of fear, despair and the irrepressible urge to blame somebody, is to keep the team methodically on track in search of a solution that gets your client back in the game to win the deal.

That’s how I got to know Richard Elmslie: we met on one of those deals. Together Richard and I and our teams spent almost a year working for our client on a multi-billion dollar acquisition. Let’s call it Project Emu, after the enormous, ungainly Australian bird that can’t fly.

Almost three thousand years ago, the ancient Hebrew prophets described the experience of being transformed through a crushing and searing personal ordeal as undergoing the “refiner’s fire”: it starts with crushing a person into shattered lumps of their previous self–and then those lumps are dumped into the cauldron of circumstance, where all remaining appearances and self-delusions are melted away, revealing any gold within a person’s true inner self.

For most people, a billion Dollar deal is a refiner’s fire, but it was actually fifteen years after Project Emu when I learned about the first time Richard Elmslie was subjected to the refiner’s fire.

What I Found Out At Barbara Elmslie’s Funeral

Richard’s intelligence, retentive memory, and intense focus were all very apparent when I worked with him on Project Emu. But what really got my attention was Richard’s character, which under pressure repeatedly displayed what we once called virtues. I found out why at the funeral of his mother, Barbara Elmslie.

Barbara’s service was held at a retirement village on the outskirts of Sydney where she and Richard’s father Peter lived. Barbara had died suddenly and unexpectedly at the age of eighty-three after gallbladder surgery, and like everyone else who was invited, I canceled other plans in order to attend. I arrived early, and watched with growing surprise as people poured into the auditorium. There must have been three hundred people in the audience by the time the service began. As I listened to the warm, loving tributes I continued to wonder why so many people had gathered for the funeral of an ordinary eighty-three year old woman, who was neither prominent nor famous. Clearly there was something special about Richard’s mom.

When Richard stood up and spoke about his mother I began to understand.

Richard told the assembled mourners he was an undiagnosed dyslexic when he was a boy. Back in the 1960s he was assumed to be mentally retarded, to use the language of that time. His mother Barbara’s response was to roll up her sleeves and do everything she could to get Richard through Year 10 in high school. In Australia this is when students who want to learn a trade can take what used to be called the “School Leaver’s Exam” to officially complete their formal education. As Richard told us listeners, Barbara was determined to make sure her beloved son Richie had a shot at a decent, happy life as a carpenter or plumber.

This was astonishing. When Richard spoke at his mother’s funeral, he had soared far higher than the most successful plumber, and any carpenter since Jesus Christ. He’d been one of Australia’s top investment bankers, and was now a co-founder and co-CEO of the asset management company RARE, with billions of funds under management.

I had no idea Richard had overcome such a tremendous disability during his boyhood. This was the first time he ever publicly revealed his dyslexia–and it came as a complete surprise given his stellar career. In the fifteen years I’d known Richard, I’d repeatedly seen him operate at the highest level while interpreting and generating complex written information.

The huge contrast between Barbara’s original goal for her Richard and what he had achieved forty years later was mind-blowing to those of us listening that day in September, 2016. It made me think back to what I had first learned about Richard on Project Emu, and I wondered if somehow his struggle to overcome dyslexia explained the great mystery about him.

Because as successful as Richard already was on the day he spoke at his mother’s funeral, with even greater success still awaiting him in the future, what makes Richard Elmslie truly special is that he is an honest man.

The Emu Deal

There’s no easy way to learn something like that about someone, and you wouldn’t willingly do what it usually takes to find out. To find out someone is honest, the odds are you have to be in a pretty vulnerable situation yourself, and the temptation for the other person to screw you has to be pretty high: otherwise, passing the test means little.

Project Emu was the acquisition of a huge electricity transmission company. Not long before Richard and I met on Project Emu, he had successfully completed the biggest M & A deal in Australian history. Richard and his investment banking team were on a hot streak. But Richard didn’t have a client for Project Emu, and my investment bank did—a big, powerful US corporation that already owned a major electricity generator in Australia. Our client was the frontrunner to win Project Emu.

Project Emu

Photo 120833213 | Ravindran John Smith | Dreamstime.com

Just as our investment banking team started work, our client appointed Richard and his team as co-advisors with us; it looked like bad news—probably the beginning of the end for us. Most investment bankers treat a co-advisory opportunity like a hunting license, an opportunity to turn the client against the other advisor and steal the entire multi-million dollar fee.

We were weakened by the contrast between Richard’s winning record and the record of our Head of Corporate Finance, who was well known in Australia for losing five big M & A deals. Each time, his clients had come close to winning—in a couple cases, excruciatingly close—but none of them won a single deal. He was a good guy and a great rainmaker, but a dark cloud hung over his head as an investment banker. Years later he would go on to great success in another field.

Financial Models and Reality

The arrival of Richard and his team seemed to indicate our days on Project Emu were numbered. Still, there was nothing to do but get to work organizing the multitude of experts and domain specialists on the acquisition team and start building the financial model.

A financial model is the heart of the work performed on a billion-dollar acquisition. The model is based upon thousands of detailed, highly accurate pieces of information. An investment banking team collects this information, breaks it down into numerical values, and then loads them into a model specifically designed to replicate the target company.

The purpose of a financial model is to act as a guide to the future, to help a client and their investment banking team predict how profitable its acquisition will be in the years ahead. A model is often used to project twenty years into the future. We know from numerous examples in the financial markets and the domains of policy and scientific forecasting that a computer model is a lousy tool for predicting the future.

But it’s the best one anyone has invented so far.

Several months into work on Project Emu, the stress of the deal and the exhausting 18 hour work days caused our financial modeler to have a breakdown and he quit. It was a fundamental, crippling, blow to our team’s position on the deal.

Naturally, on his team Richard had one of the best financial modelers in the business: Nick was a former New Zealand rugby player who was exceptionally intelligent and absolutely calm at 3:30AM when things always went wrong. Nick had already been managing the financial model on a dual basis for months, and would take over every evening when our guy went back to the hotel to sleep. Now Nick took over the financial model, positioning Richard to take over the deal.

Richard could have lobbied the client to terminate our team but he didn’t do it.

But another blow to our prospects was not far ahead: only two months before final bids were due on Project Emu, I suffered a pancreatitis attack and had to go to the hospital for an operation to remove my gall bladder, the same operation after which Richard’s mother Barbara was to die fifteen years later. I, however, was back on the deal within a week although my doctors urged me to try not to work too hard.

At this point, our investment banking team was like an emu with a broken leg. Richard had the very clear, easy prospect of an extra couple million dollars: all he had to do was get the client to fire us from the deal so he didn’t have to split the success fee. It wasn’t illegal, in fact, it’s a standard investment banking gambit, part of the game—and a very lucrative one.

But Richard didn’t do it.

In the end, our client came in second on Project Emu. Perhaps our financial model didn’t recognize the full value of Project Emu, or perhaps it was accurate and the winning bidder paid too much, incurring what is known as “Winner’s Curse.” Or perhaps our Head of Corporate Finance’s karma was the decisive factor in the end. I’ll never know, but I had learned that I—and everybody else—could trust Richard Elmslie.

Your life, your wife, a multi-million dollar fee: can there be a higher standard of trust?

Who Can We Trust?

When you’re working on a Giga Deal you need somebody who is both highly competent and extremely honest, because as Leo Hepsis observed, trust isn’t only one thing.

When you require the level of competence necessary on a billion Dollar deal, only a tiny number of people have the necessary skills and experience. If you can afford them, you want somebody who is in the top 10%, or 5%--or ideally 1%--on your deal.

The same is true for honesty, which like other psychological traits is subject to a normal bell curve distribution, but how do you know whether or not someone is honest?

The problem in the financial markets is that as you move to the right along the competence curve, the rewards and temptations facing you grow exponentially. Some people are able to resist greed and the lust for fame and status, but the huge rewards and temptations that appear at the extreme right of the competence curve tend to erode even the strongest characters. It’s not always true that the highest competence and the highest honesty are unlikely to be found in the same person, but that’s the way to bet. Except in the case of Richard Emslie.

How did Richard develop this level of honesty while rising to the top of a profession with a reputation that rivals politics for conflicts of interest and institutional corruption?

Richard the Outcast

There’s an old joke about the Irish peasant walking along the road when a tourist stops his car, rolls down the window and asks directions to a particular place. The Irishman thinks about it, scratches his chin, and says, “Well, if I were to be going there, I wouldn’t start from here.”

Young Richard was a troublemaker. He enrolled in first grade at Wahroonga Bush School, and by second grade it was apparent that Richard, despite being a talkative boy, was struggling to learn to read. His eyes were tested, which demonstrated his eyesight was perfect. Back in the Sixties that removed any excuse for failing to read, and the only remaining explanation was stupidity. In addition, because of Richard’s talkative, out-going personality, his teachers considered him not only dumb but disruptive, and he was repeatedly thrown out of class:

“I’d be put on the wooden balcony, and I’d sit there for half an hour or forty minutes, and then they would let me back in. Then I’d come in, but I didn’t know what they were doing, so I’d start talking to someone, and then I’d get kicked out again.”

Richard at Wahroonga Bush School sans clean shirt and tie

From second grade Richard was repeatedly thrown out of class, and when that didn’t have any effect on his behaviour, he was caned. Caning meant Richard was required to stand at the front of the classroom, extend his hand, and receive a blow from a hardened piece of bamboo on his palm. The punishment causes the palm to callus. By the time Richard finished fifth grade he had been caned twenty-nine times.

Contemporary photo of Wahroonga Bush School showing the balconies where young Richard was once exiled

Understandably, Richard’s mood had darkened considerably by this time. Richard began to see himself, in his own words, as an “outcast.”

Given the misunderstanding and disapproval that surrounded him, even his good attributes exacerbated his plight. His intelligence and talkativeness made him seem rebellious and disruptive; he grew big and strong for his age, and by the time he was eleven or twelve, he was hanging out with older boys who were up to no good.

One weekend, Richard’s new friends suddenly pinned his arms behind his back while a teenager named Percival burned Richard’s chest with a cigar. On Monday, Richard arrived at school, found one of his tormentors and punched him in the mouth, knocking his front teeth out.

By the end of fifth grade, Richard was on his way to being expelled from public school, not an easy feat in either Australia or America.

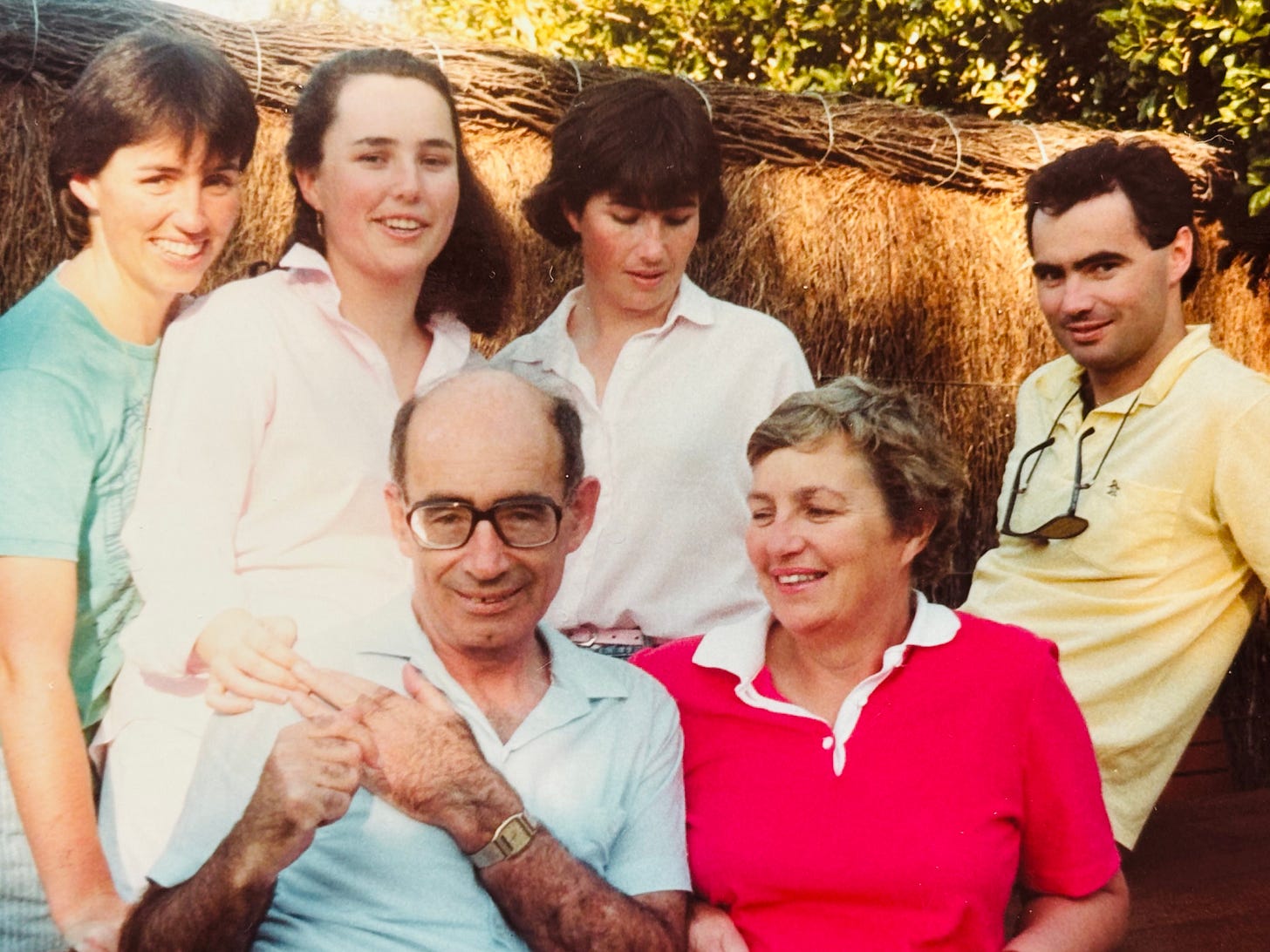

Richard was Peter and Barbara’s oldest child and their only son, but by now they also had three daughters to look after as well. For years they had been told by the experts that their son was stupid and disruptive, and now he was becoming violent. As matters came to head, Richard’s parents had to decide whether to give up or continue to look for a way to help their son, without depriving their well-behaved daughters.

I have three adult children, and when your children have problems it can be demoralizing. You feel like a failure as a parent, and your childrens’ problems feel like a reflection on you and your spouse, either genetically or because of the upbringing you’ve provided.

It takes a special kind of love, faith and hope to persevere in the face of such persistent, discouraging criticism of one’s child by professionals who are seemingly experts.

Barbara and Peter Elmslie - Richard’s loving and determined parents

Richard’s parents did have that love and faith, and Barbara went back to university to study teaching, in the hope of learning something that might help Richard. That’s where she learned about dyslexia and realized it must be Richard’s real problem. Dyslexia was only beginning to be understood, and it wasn’t clear how intelligent Richard might be. But it didn’t matter: Barbara was determined to help Richard alter his path from becoming a juvenile delinquent and learn to read well enough to get an honest job as a tradesman.

Hoping for his future, Richard’s parents paid for years of tutoring, and they also arranged for Richard to get a fresh start at a private school, Barker College. In sixth grade, after almost four years of misunderstanding, rejection and punishment, things started to turn around for Richard.

“Thank God my mother and my father did,” Richard says now. “They didn’t have a lot of money–it cost a lot, I had a lot of tuition . . . For years, I had extra tuition. And I think actually it was to the detriment of my sisters because I got so much focus, it was like having one disabled kid in the family–I was it.”

A still-disgruntled Richard in Year 6 at Barker College

At his new school Barker College a teacher named Mr. Porter took a liking to the gregarious but troubled and struggling school boy. Richard remembers, “I probably needed somebody to take a liking to me, to support me. Didn't matter what they supported, but I did need some support, because at that public school I didn't get any support because I was just considered a nuisance kid.”

Extreme Out-Performance

Young Richard’s original goal when he transferred to Barker and began getting tutoring also paid for by his parents, was very simple: “I was only twelve or thirteen,” Richard says. “I wanted to be normal. I wanted to read.”

At Barbara’s funeral, as I listened to wealthy, successful Richard talk about his childhood struggle to overcome dyslexia, I realized he had something in common with another friend of mine, Mike Agostini, whom I have written about here.

As a boy Mike lost his left kneecap in an accident, but Mike grew up to become the world record holder in the 100 meter dash, the “fastest man in the world”, and went to the 1956 Melbourne Olympics. Like Richard, Mike overcame a very serious disability, hoping only to overcome the challenge enough to live a normal life, but instead he wildly out-performed his own, and everybody else’s, expectations for his life.

I was eager to understand how Richard’s battle to overcome dyslexia had not only given him the skills and attitude to reach the extreme right of the competence curve, but–more importantly–the extreme right of the honesty curve.

Richard has always been a fluent and articulate talker—that’s why he got into so much trouble as a schoolboy—but his brain doesn’t visually identify and process letters like the ones you are reading now. Dyslexia distorts the visual signals of letters received by Richard’s brain, and as a result, he can’t recognize individual letters and the combinations they form such as “th” or ‘ng” or “ck”. So Richard is unable to convert them into pronounceable sounds.

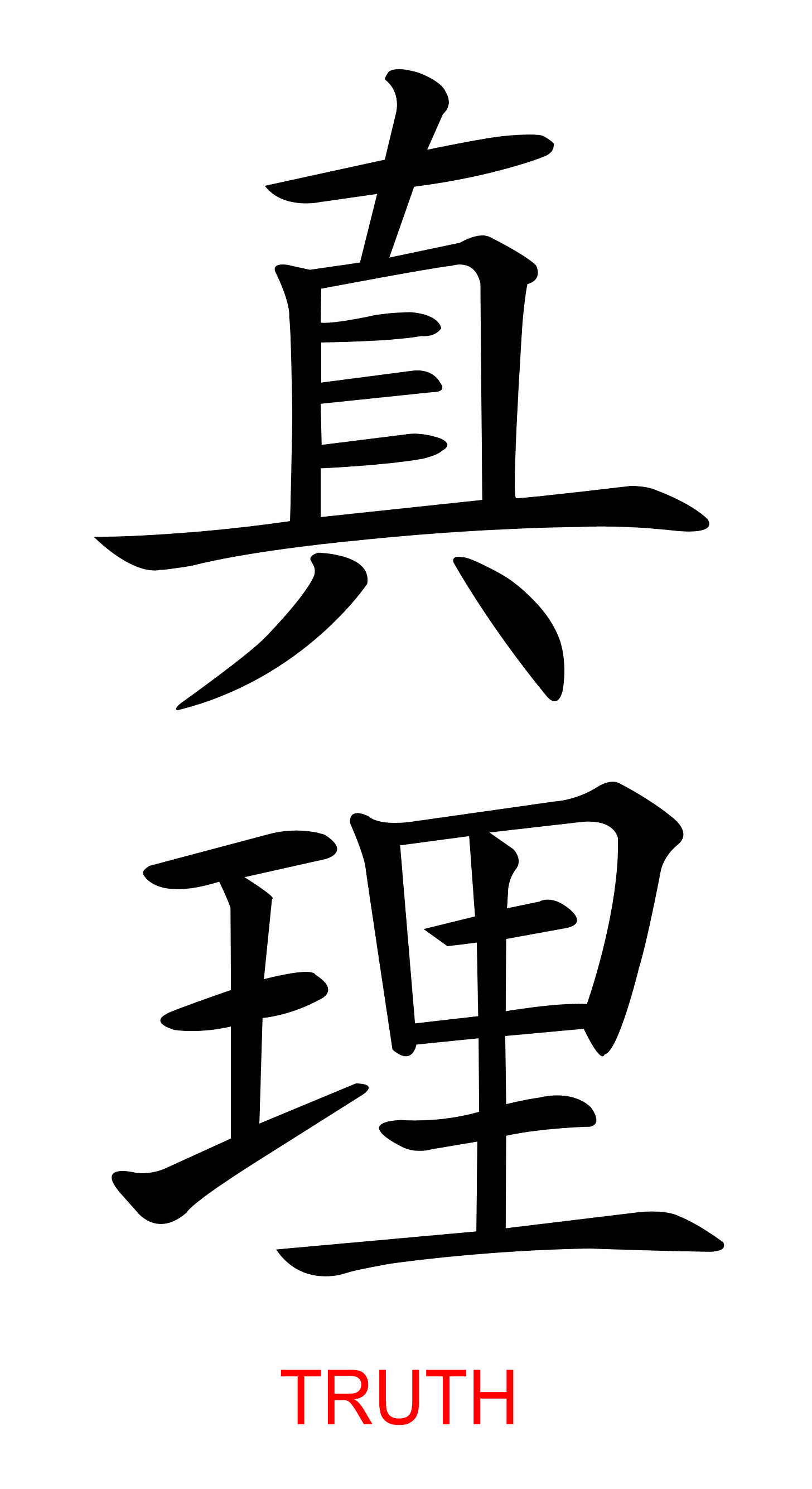

To Richard, written words appear as unintelligible symbols, similar to the way Babylonian cuneiform looks to us. The parts inside the symbols, which are letters to us, mean nothing to Richard:

Remember, Richard is highly intelligent and articulate–that’s what got him repeatedly caned–but his signal-processing capability when applied to words is impaired.

Richard’s solution was to remember the symbols themselves, and learn to associate them with the spoken words he knows and uses so well. The solution was simple–but not easy. In fact, the solution was so difficult that few people would have persevered until they succeeded.

Richard did.

Over many years, starting when he was finally given a chance at twelve years old, Richard overcame dyslexia by memorizing thousands of written words as symbols. Then he associated those symbols with the spoken words he knew, and was able to develop his own private mental map of the English language that didn’t require him to identify individual letters and combine them into words–a function his brain doesn’t possess.

Richard didn’t know it when he began learning to read, but in English 360 words make up 75% of an average person’s vocabulary, and 2,700 words make up 90% of an average person’s vocabulary. Of course, there are many domains full of specialized vocabulary, and in order to study high school textbooks Richard had to learn to recognize thousands of words by memorizing them as symbols. Still his challenge was more manageable than it seemed at the start.

Richard spent many years acquiring expertise similar to the ability of a Mandarin speaker to memorize Chinese ideograms:

19050527 © Heinz Teh Chee Siong | Dreamstime.com

Mandarin ideograms have a purely abstract relationship to the spoken Mandarin words they represent. A Mandarin speaker has to learn a minimum of 1,000 ideograms to achieve a basic reading level in Chinese, and needs to recognize about 2,500 – 3,000 ideograms in order to read without constantly resorting to a Mandarin dictionary.

But once Richard started learning to read, he wasn’t satisfied with attaining the level required to be a carpenter or plumber. It was a difficult, tedious process and required prolonged, intense concentration, but gradually Richard built up a storehouse of hundreds, and then thousands, of word symbols that he connected to spoken words, learning to read well enough to be accepted to university.

After he lost his kneecap, Mike originally only wanted to be able to play with his friends again–but once he learned to run, swim and ride his bike again, Mike didn’t stop there. He just kept training, and getting faster and faster, until he was the fastest man in the world.

Mike and Richard each began their journeys of self-improvement by focusing on the next step, and then the next step after that, neither boy without knowing what was going to happen or how far they would go in life.

Nobody told young Mike that if he tried to walk again he would one day become the fastest man in the world. Nobody told young Richard that if he learned to read, he would one day become a top investment banker, then the co-founder and co-CEO of a funds management firm investing billions of dollars.

Early in life, Mike and Richard confronted devastating personal flaws that seemed to disqualify them from a normal future, but that didn’t have to be defining. Instead, the effort they were both willing to put in—with no guarantee, or even much hope, of results—was what ended up defining their lives.

A confident Richard, upper left, now on his way to university to study accounting

By the time he was in Year 12, Richard had already exceeded his own, his family’s, and his teachers’ expectations by showing the intellectual potential to study for a professional career.

By the time Richard enrolled at the University of New South Wales, he decided to follow in his father Peter’s footsteps and become an accountant. Accounting, of course, is mostly a mathematical subject.

It seemed like a good decision.

The Refiner’s Fire

Suffering is not necessarily meaningless, nor is its effect necessarily destructive. Since ancient times, the refiner’s fire has been a daunting image for the complete transformation a person undergoes when tested by the most extreme situations in life.

Do we need transformation? We are constantly assured we already know what’s best for ourselves, we just need to identify our desires and do what comes naturally. A common goal of the contemporary therapeutic process is to assist us to look deep inside ourselves, so we can find our authentic self and learn to fully express our true selves. Therapists encourage us to find and heal our inner child. Social media tells us “follow your bliss”.

By contrast, Hebrew prophets used the image of the refiner’s fire to explain how inner transformation is initiated by external events and determined by how we choose to respond to those circumstances.

The image of the refiner’s fire arose out of the national tragedy experienced by the prosperous and thriving kingdoms of Israel and Judah during the 6th century BC. They were attacked and after long sieges defeated by Babylonian armies, who murdered, raped, impoverished and enslaved the survivors, and then marched them across the desert into captivity and exile in Babylon.

Instead of viewing the human essence as an inner child who needs to be nurtured and healed, ancient wisdom teaches human beings are like lumps of gold ore–which don’t look like much to the untrained eye–and must be subjected to terrible ordeals in order to eliminate the worthless or toxic dross of our outer selves and reveal the precious gold of our nature. Gold ore is mostly worthless minerals or toxic impurities, and the few traces of gold are often scarcely visible in the ore’s natural state.

Would you know gold if you saw it?

Photo 20315432 / Gold Ore © Zelenka68 | Dreamstime.com

The first step of the refining process after the gold ore is mined is to crush it into granulated rubble. Depending on the grade of ore, this rubble is further subjected to extreme pressure until ground into dust. Most of this dust is worthless material, but a tiny, precious percentage of this dust is gold.

Before the Babylonian army appeared at the gates, Jeremiah warned the people of Jerusalem hard times were approaching, but he reassured them that their suffering would have meaning, because it was necessary for their transformation: “Therefore this is what the Lord Almighty says: “See, I will refine and test them. (Jeremiah 9:7). To the survivors in their Babylonian exile, Isaiah reassured them the refiner’s fire was how God had tested and purified them: “See, I have refined you, though not as silver; I have tested you in the furnace of affliction. (Isaiah 48:10)”.

When Richard was seven or eight years old, he seemed to be a stupid boy with a bad attitude and a growing inclination for violence. The refiner’s fire offers hope that suffering isn’t meaningless, but the concept is still difficult to accept. What kind of universe would allow Richard to be stigmatized as stupid, and humiliated and punished for years? The prophet Daniel explains suffering sometimes comes to good people in order to make them great: “Some of the wise will stumble, so that they may be refined, purified and made spotless until the time of the end.”(Daniel 11:35).

More deeply, God’s presence itself is compared to a refiner’s fire: “But who can endure the day of his coming? Who can stand when he appears? For he will be like a refiner’s fire. (Malachi 3:2)” So when Richard was being sent outside the classroom, caned, scolded by teachers and taunted by other children, Richard was in God’s presence; arguably, his unjust suffering was a sign that because of his great inner strength and character, he had been marked out for greatness.

The ancient prophets show us Richard’s future extraordinary success was rooted in how Richard chose to respond to his suffering. The prophet Daniel warned that our response to affliction determines whether we are purified or destroyed by the refiner’s fire: “Many will be purified, made spotless and refined, but the wicked will continue to be wicked. None of the wicked will understand, but those who are wise will understand.” (Daniel 12:10)

Richard’s personal values, and the values of the Elmslie family, channeled Richard away from self-pity, resentment, making excuses and blaming others. Instead, encouraged and funded by his parents, and selflessly supported by his sisters, Richard did what he had to do–hoping just to become normal.

By the time he got to university, Richard had suffered many painful experiences. But there were plenty still ahead.

The golden dust, after being crushed and ground at high pressures, is subjected to poisonous elements such as lead, chemical bath in strong acids, and in modern times to electro-magnetic processes that further purify the gold. For example, a sodium cyanide solution can be added to the crushed, ground dust, dissolving the gold. The gold is then precipitated from the saturated cyanide solution.

Photo 145810651 © Adwo | Dreamstime.com

After graduating from university, Richard worked for three years in a chartered accounting firm, earning less than the secretaries (back in the day when there were secretaries), while preparing for the Professional Year (“PY”) exam that would certify him as a Chartered Accountant. The PY exam is formidable, but even worse, the preparations for the PY exam required Richard to write a 5,000 word essay every three weeks on all the key subjects an accountant is required to master.

So now Richard had to memorize by sight another thousand or so technical words—Profit & Loss, balance sheet, audit, consolidations, tax, and all the categories within those concepts—and then he had to produce his own written essays.

At the end of an excruciating year of writing essays, Richard was eligible to sit for the three hour PY exam. The PY exam is notoriously difficult and has a high fail rate.

Richard failed the PY exam.

Richard had a choice after failing the exam. Being a Chartered Accountant is the most highly regarded qualification in the accounting profession, but there are plenty of good jobs for accountants who don’t achieve the standards required to be a Chartered Accountant. One of the early clear examples of the gold starting to shine in Richard’s character was his decision to shrug off his failure on the first PY exam, study for the extra year, and sit the PY exam again.

This time Richard passed and became a Chartered Accountant.

The Confucian Superior Man

Richard’s success going from a dyslexic boy to Chartered Accountant can be understood as a process of acquiring skills through tedious repetition and sustained focus, over years, in order to re-wire his neurological system to over-compensate in other ways for the signal processing deficit of his dyslexia. The remarkable resilience and adaptability of even the adult brain to re-wire itself and acquire new or enhanced capabilities is a previously unknown quality known as “brain plasticity.”

Research in cognitive neurology was originally based on early case histories of severely injured people who were desperate enough to speculatively embark on tedious, extended regimens of repetitive movements or mental exercises, with only the faintest hope of improving enough to have normal lives. Cognitive research has established that this is precisely the way to activate brain plasticity, and that three - nine months is generally the period required to begin to see significant improvements.

After being misunderstood and punished for years, Richard was desperate, too. When he was finally diagnosed with dyslexia and provided the resources his parents made available to him, he embarked on the long journey to learn to read. But a process of personal redemption born out of desperation and desire to be normal became something much greater.

Those years in high school, university and as a junior accountant of tedious and exacting self-discipline developed Richard’s brain and also developed his character. Subjecting oneself for years to a monk-like level of self-discipline and focus requires to optimise brain plasticity also optimises the intangible qualities we call personality. The rapidly developing field of cognitive neurology is empirically establishing that high performance is linked to the classic virtues taught by all the world’s religions and mindfulness traditions: self-discipline, patience, empathy, honesty, long-suffering, gentleness, peacefulness.

Once gold ore has completed the chemical, acid or electro-magnetic process, it is transferred into a crucible and subjected to temperatures exceeding 1,948 degrees Fahrenheit. Residual impurities float to the top of the molten gold and are skimmed off. Producing purified gold is a harsh, pain-staking and dangerous process.

Photo 23379317 / Molten Gold © Alena Brozova | Dreamstime.com

The latest cognitive neurology research establishes an association between the type of protocols that leverage brain plasticity and a cluster of traditional virtues, but we can look to the world’s oldest continuing culture for a powerful confirmation of this connection. As discussed earlier, the process Richard developed of memorizing written words as symbols in order to overcome his dyslexia is very similar to the way Mandarin scholars have been trained to read ideograms for thousands of years.

Traditional Chinese culture is world-renowned for its lofty ethical standards. Cognitive neurology has revealed how the Confucian “superior man” not only acquires a knowledge of thousands of Mandarin ideograms but develops a character of benevolence, perseverance, harmonious relations with others, wisdom and honesty.

The data is clear that East Asian populations living in both Australia and the United States have the lowest crime rates, and some of the highest educational and income levels, of any ethnicity in those countries. In his struggle to overcome dyslexia Richard also developed the moral qualities of the Confucian superior man.

The essence of science is pattern recognition. We can predict countless scientific phenomena with the precision required to invent and deploy the technology that has transformed human existence, but the foundation of these phenomena is mysterious. We know the “how” of much of the physical world, without knowing anything about the “why”.

Why do so many human characteristics fall into a bell curve? We don’t know why, but we know they do.

The I Ching, “The Book of Changes”, the oldest book in the world, taught thousands of years ago that causality is a deeper mystery than we may find it comfortable to acknowledge: ‘Intelligence expressed itself from the beginning in three forms— humans, animals, and plants, in each of which life pulses with a different rhythm. Chance came to be utilized as the fourth form: the very absence of an immediate meaning in the random permits a deeper meaning to be expressed.’

Understanding that we can see patterns without understanding them, I think there are two possible explanations for Richard’s honesty.

The first explanation lies hidden in Richard’s original goal to read well enough to live an ordinary life. Nobody told him when he started memorizing symbols and associating them with spoken words that he would one day be a wealthy and successful man. As a boy, Richard needed to find and nurture other kinds of motivations within himself in order to persevere during those long early years, when the results he achieved were so modest.

Had he subjected himself to exactly the same tedious, multi-year process motivated by greed and a lust for success and fame, he would probably have achieved the same neurological hyper-trophy but he would have developed a very different moral framework.

The second explanation is hidden in the difficulties intrinsic to reading as a dyslexic–or a Mandarin scholar. Attaining virtuosity with symbols–whether mathematical or linguistic–is a process full of temptations. A plumber or a carpenter displays his prowess by creating physical systems that function in an exceptional way. A lawyer or investment banker can be a virtuoso at manipulating numbers or words in ways that are malicious or misleading. Given the stakes of a Giga deal, a white collar professional comes under tremendous pressure to apply their intelligence and expertise in ways that increase the likelihood of winning by bending the rules as far as possible, right up to the point, without crossing the line, of being illegal.

To this day, Richard works hard to perceive the meaning conveyed by the written word. When Richard reads the Australian Financial Review or the Wall Street Journal, his virtuosity is expressed by his ability to access what is now a huge mental database of thousands of word-symbols and match it to the meaning of the words he reads.

The meaning of words are more real for Richard because he has confirmed millions of times in his life that a particular symbol he’s memorized matches a word he knows, and so words seem more concrete and significant to Richard than they do for the many white collar professionals who treat words as mere arbitrary constructs with no stable meaning, ephemera that can be altered by the stroke of a pen, or a few keystrokes. Investment bankers, financial traders, lawyers, consultants, tax specialists, and journalists who devalue words often show contempt for reality itself and reduce the distinction between right and wrong to whatever happens to be legal, or generally accepted in their circles.

By contrast, Richard’s quest to discover the meaning of those mysterious symbols we effortlessly recognize as words seems to have convinced Richard that words represent something real, and their meaning is something important, not meant to be gamed and manipulated. Psalm 12 declares that God’s words themselves “are flawless, like silver purified in a crucible, like gold refined seven times (Psalm 12:6),” and along with learning to read, Richard acquired a belief in the existence of truth.

A Golden Career

Mr. Porter at Barker College was only the first of many people who began to recognize the gold in Richard. Richard was now a Chartered Accountant and a seasoned young professional, and he was being noticed by both talented peers and shrewd mentors. He was becoming known for his extraordinary memory, his capacity for intense focus, his tenacity, and his willingness to persevere when everybody else had given up hope.

Richard and the Elmslie family

His days of hoping to be a carpenter or plumber receding behind him and starting to make his way in his father’s profession, Richard now set his sights even higher and he decided to become an M & A investment banker. Within a couple years Richard was hired by BZW and sent to London to work in the new field of privatizations.

Richard and I didn’t meet then, but we happened to be working in London at the same time. My office was directly across the street from the Bank of England. It was a time when privatisations were considered exceptionally risky, and I remember the feeling of fear that surrounded those early deals.

The UK in the late 80s was Richard’s proving ground as both an M & A advisor and a privatization and infrastructure specialist. After London, BZW sent Richard to New Zealand, where the deeply indebted New Zealand government and decided to privatise New Zealand Telecom. Richard advised the management of New Zealand Telecom on the sale. On Richard’s 30th birthday, he successfully completed the NZ$4.2 Billion privatisation, which was the largest privatisation in New Zealand history.

The period in Richard’s life when he had worked extremely hard for years while producing only modest results was over. The skills he had acquired while learning to read and the over-development of other areas of his brain that was required, combined with his strikingly good character and the circumstances in which he now found himself to produce an exponential growth curve. Richard continued to experience setbacks, tactical defeats, and formidible challenges, in fact several of the hardest deals he ever did were late in his career, but now he knew that his skills and mindset were equal to any challenge he was likely to face:

By this time, I was in Latin America making equity investments in newly privatized infrastructure myself. We were all looking across the Pacific at what was going on in New Zealand, where Richard was right in the middle of it.

After the blockbuster sale of New Zealand Telecom, Richard was the natural choice for BZW to assign to Melbourne, Australia to lead the M & A team working on privatizations in the highly indebted State of Victoria, whose newly elected Premier Jeff Kennett was determined to restore the credit-worthiness of the State.

By late 1994, when Richard had just turned 34, he was leading the BZW investment banking team advising clients on buying electricity distribution assets from the State of Victoria. In 1995, his client bought the last Victorian privatized electricity distribution company for $2.1 Billion.

At the time, it was the biggest ever M & A deal done in Australia. The Australian newspaper sent a photographer to photograph Richard and his Project Finance colleague, and Richard chose a wharf on Sydney Harbour in front of the apartment to which his parents had recently moved (Richard Elmslie is on the left):

Over the decades since this photo was taken, literally dozens of photos and articles have featured Richard, but this image continues to mean the most to him, and still warms his heart when he thinks about the sacrifices his family made to make his first great triumph possible.

A year later, when the Australian Federal government decided to privatize its airports, they insisted Richard co-lead their advisory team, even though he was heavily committed on other M & A assignments. Before long Richard was the Head of Infrastructure M & A at BZW, and about this time we met on Project Emu.

We all intuitively understand that suffering can have a positive effect on our characters. Richard’s journey to become someone who was exceptionally good at what he does while remaining exceptionally honest is a heartening example of how good character is built by hard work and traditional virtues. It’s often said in the financial markets that ‘nice guys finish last’, but Richard’s success refutes that cynical view.

As he says today, “If I've got a goal I just focus on the goal, and everything else is secondary until I get to that goal. It’s not that I have to succeed, it’s that I hate to fail.”

Richard had to fight for the truth, and he believes in it.

That’s what make him different.

Photo 24694548 / Gold Bars © BrunoWeltmann | Dreamstime.com

...such an inspiring story Chris...and the metaphor is rich...to find the gold in ourselves and others we have to change/grow/transform...accepting the challenge and never giving up...how rad you got to know and work with this dude...

Thanks for sharing this, Chris. I needed the inspiration as someone who can feel a bit lost at times. Sometimes I feel like my weaknesses are hampering me. But this gives me hope that there's a way up.