The Secret World

Ignorance is not Bliss

“You know, your Onkel Christof just got a new assignment,” my mother said, her voice sounding eager and happy on the telephone. I had just turned twenty that day and she called to wish me a Happy Birthday. “Christof’s hated being back in Bonn and he’s just been approved for an assignment to New York.”

“Oh, wow, that’s fantastic!” I said. “He’s such a great guy.”

“This is your chance to get to know him,” my mother said. “You’ll be able to visit him in New York.”

I’d only met my mother’s brother three times in my life. Once when I was five and we lived in Munich, once in Frankfurt when I was twelve, and the third time when I was sixteen and we lived in Heidelberg. That time Onkel Christof and I had stayed up until one in the morning talking. As brief and infrequent as our meetings had been, I felt deeply connected to him.

“Sure,” I said, thinking of the heavy course load for my double major. “I’d love to–someday.”

“Why don’t you go to New York for a year?”

It was the second week of August and I was a couple weeks from starting my junior year at USC.

“After I graduate?”

“No—now! Take a year off and spend time with Christof. You two can get to know each other really well.”

“What? Mom, I can’t do that!”

“Why not? What does it matter? You can make up the time. You’re young.”

Mom had been becoming increasingly frisky in the last year, but this was an unprecedented break with the austere, goal-oriented ethos of our family. I was executing my father’s multi-decade plan for me to graduate with honors, get into the best law school in the country, go into politics, and become President of the United States.

Drop out of college and go hang out with my diplomat uncle? I couldn’t believe it.

“Oh, I don’t think I could do that, mom,” I said. “But maybe I can transfer for my junior year. That happens a lot.”

“Whatever it takes—just get out of LA and go do something different in New York with your Onkel Christof.”

Mom had always encouraged travel. It was she who had approved the summer I spent in Sevilla, Spain when I was sixteen, and my Eurail trip with five friends, three of whom were attractive young women, when I was seventeen. My mother’s laissez-faire attitude about travel irreconcilably contradicted the other harsh, punitive Calvinist aspects of my upbringing.

That summer, she was emerging from years of depression. About a year and a half before, mother had established some kind of relationship with an old family friend named Arnie, who was an airline pilot. My father disapproved and as far as he was concerned, Arnie was a former family friend. But father couldn’t do anything about it.

From our perspective as young-adult children, mother was no longer being the strict, forbidding, pitiless disciplinarian. Still, her proposal to delay my prescribed march towards the Presidency revealed an entirely unprecedented level of carpe diem philosophy.

“Maybe I can get into Columbia,” I suggested. “My grades are good enough.”

“Sure,” my mother said indifferently. “I’ll talk to Christof about you coming and you find out if you can transfer to Columbia.”

It turned out a New York adventure was very do-able, assuming I could get accepted to Columbia.

My uncle immediately confirmed I was welcome even though we hadn’t seen each other since he’d visited us in Heidelberg. We’d stayed up for hours the night of his visit debating the death penalty. Even though Onkel Christof was a career diplomat he had been educated as a lawyer, the career I had chosen. I supported the death penalty, and Onkel Christof opposed it. Ultimately, his position was that he personally did not feel sufficiently beyond reproach in order to judge and condemn another man to death.

It was an interesting point, because by my parents’ standards he was a deeply flawed man, a sinner. Mom had prepared for his visit by buying four bottles of beer, which had never before been permitted to defile our refrigerator. I remember looking at them in wonder glowing in their rack on the refrigerator door before my uncle arrived. He also smoked, another sin for which my parents had no tolerance because it violated his body, the temple of the Holy Spirit.

If Onkel Christof had asked Jesus Christ to “come into his heart” he had never mentioned it, and the fact he’d married a Muslim Persian who rejected all religions as oppressive nonsense suggested not. Yet my mother adored her brother, loved him unconditionally, and accommodated his every wish enthusiastically. In other words, Onkel Christof wielded the only form of power that mattered in my family: he had my mother on his side.

After dinner on the evening of his visit with us in Heidelberg I defeated him in a game of chess. I once won a game of chess against my father back when I was eight; it was a fluke, and that was the first and last time I ever beat him at chess. Onkel Christof was tall and skinny, with a thin chest and a smoker’s cough. My father was even taller, 6’4”, and although by his forties he was starting to let himself go he’d been a paratrooper in the 82nd Airborne, was an excellent shot with a variety of weapons, knew how to box, and was a decorated combat veteran of two wars. It didn’t matter: Onkel Christof wasn’t as good as chess, or anywhere nearly as strong, but he was powerful, and my father was not.

In his appearance there was no posturing, no broad shoulders, no brisk marching steps. Onkel Christof was gentle, intellectual, warm, kind, cultured, and charming, with a quick subversive wit. If there was something verdorben, corrupt, about him the possibility was never mentioned.

He fascinated me, and I loved and admired him.

At that stage, however, I was still my father’s son, despite deep and growing fissures in our relationship. I wasn’t going to drop out of USC for a year and go live with Onkel Christof, Tante Furugh and my eleven-year-old cousin Alex. My father had studied Nuclear Engineering at Columbia University, so I applied to Columbia. My father had lived at International House (“I House”), so I applied to I House, too. I House is a graduate student residence that doesn’t accept undergraduates, so my father called the President of I House, an old friend of his, who admitted me under the “poet’s exception”. The planning for my New York adventure straddled the two, increasingly opposed, sides of my family heritage.

I also had my own agenda.

Going to New York would bring me close to Nicole for the first time since our brief meeting in San Francisco just before we started college. Years before in Korea, both my parents had done everything to thwart Nicole and me, but now they were inadvertently collaborating to bring us together—or at least to bring us reasonably close.

With my invitation from Onkel Christof and a place to stay at I House confirmed, I mailed my application to Columbia and reached out to Nicole to tell her my plans. I don’t think I wrote Nicole, I think I called her at the summer camp in Vermont where she was working. She greeted my news enthusiastically, and we both rejoiced at the prospect of seeing each other again.

Summer ended and the Fall semester began at USC. Soon I received a notification from Columbia. My application had been received, and while it was too late to accept me for the Fall semester 1980, I was being considered for admission in the Spring semester, which would start January, 1981.

Meanwhile in Massachusetts, Nicole started her first semester at newly co-ed Williams College. Nicole had told me at the beginning of the summer she would be transferring to Williams. I probably got the idea of transferring to Columbia from Nicole. Nicole had been considering leaving all-women Smith College since the beginning of her freshman year, and I knew the reason for the transfer was because she wanted to be around men.

Nicole had reassured me in her letter at the beginning of the summer, telling me how much she wanted to see me again, and at the end of the summer when I called her with the news I’d applied to Columbia, Nicole had told me she couldn’t wait to meet again on the East Coast.

But then she started at Williams, and as the first weeks of September went by and I didn’t hear from her, I felt a growing sense of foreboding.

In late September I received Nicole’s first letter from Williams. Nicole no longer seemed concerned about sparing my feelings, and she wrote to tell me she was very happy about transferring to Williams, without going into specifics.

In truth, I didn’t want to know any specifics.

I had been aware since our sophomore year of Nicole’s growing indifference, which was intermittently brightened by warm letters and our conversations when I telephoned her. Then in a letter she sent in February, Nicole wrote me with the crushing news she had started sleeping with men. Although she made it very clear in her following letters how much she wanted to continue our relationship, to which I agreed, my feelings were deeply wounded.

For the past two years, while I was at USC in far-away Southern California, the preppies at Amherst had had every advantage, as events proved. Now that Nicole was at Williams College, surrounded by men, it was clear prospects for our relationship were dwindling fast. If I was admitted to Columbia, I might get to the East Coast in time to meet Nicole again and re-build our relationship on a new, mature foundation. Maybe not—but either way, the opportunity to see Nicole couldn’t come soon enough. Time was not on my side.

But I had a big problem: guys are supposed to know what they’re doing.

Since leaving Korea after our freshman year in high school and moving to Germany, I had reserved myself exclusively for Nicole, putting all serious dating on hold during my high school years. I almost lost my virginity on the Greek island of Corfu the summer between high school and college, but at the last minute I didn’t do it, and the experience taught me nothing about flirting and dating girls. The rules on a nude beach in Corfu certainly didn’t apply on the USC campus—much less with Nicole. My first two years at USC were more of the same, even after I joined a fraternity.

Sex? I didn’t even know how to flirt.

When we saw each other again, Nicole wasn’t going to tell me what to do. Nicole would expect me to act confidently—emotionally, romantically, psychologically. She would be watching, observing and judging. I wasn’t even sure if I was ready to have sex yet, even with Nicole. I just wanted to know how to handle myself.

When you don’t know the destination it’s hard to know how or where to start. Moreover, my family upbringing had taught me to conceal my true feelings behind an impassive mask. When I moved to Korea at the beginning of eighth grade, I quickly realized I was puzzling my new classmates and soon I figured out the problem—my face was expressionless. So I stood before the mirror daily for a couple weeks and re-taught myself to allow expressions to re-appear on my face to match my emotions—good and bad, happy and sad, depressed and joyful. I forced my eyes into crinkles when I smiled, I didn’t just widen my mouth, I re-activated the muscles around my jaws and forehead so that full expressions flowed across my face as my moods changed—at least when I was talking to others. But my natural ability to express myself spontaneously through facial expressions and body language remained impaired, and when I felt self-conscious I would become impassive and my body language was stiff.

So I hadn’t learned yet how men and women exchange the first subtle, almost imperceptible, signals of mutual interest. Romantic and sexual feelings originate when a man and a woman are in one another's presence—but how does the process start? In public social situations men and women conceal their attraction to each other, pretending to be indifferent. Nobody says what they’re really feeling.

What was the secret procedure that initiated the dance and guided the choreography of mutual approach, step by step, providing each person the opportunity to affirm or cancel the dance, as the distance closed, physically and emotionally, between man and woman? Arousal is a process, it's a liminal zone a man and a woman gradually agree to share, and the uncertainty at the beginning makes this zone an erotic and exciting place. How could I bridge the gap between the public world and the secret world?

Nicole and I had been relaxed, easy and natural together when we were fourteen, but it took us a long time, and we were on equal ground back then, both innocent virgins. The last time we had met two years before, when I drove Nicole and her father to San Francisco on their way to Smith College, wasn’t an encouraging precedent. Nicole had been taken aback by my height and deep voice.

Even if Nicole might be prepared to cut me slack when we met again, the last thing I wanted to be was a naïve bumbler. I wanted my confident, successful public self to match my intimate, private self. I wanted to be my best. The fact that I loved Nicole, and had always expected we would marry, meant the the stakes for our meeting on the East Coast couldn’t be higher.

I had been propositioned numerous times that summer by homosexual men in West LA. It was an unsettling introduction to being on the receiving end of masculine sexual desire. I realized their attraction to me was a compliment, but they seemed to care only about having sex with me—as if oblivious to my humanity, my personality, my hopes and dreams. I felt treated like a piece of meat. The most painful aspect of being propositioned by men was their crude style confirmed everything my mother had taught me about the way men behaved towards women.

From watching the mating rituals at USC fraternity and sorority parties the main impetus for sexual arousal seemed to be alcohol, drugs and music. But my intuition told me those simple expedients were for simple people and weren’t relevant to my upcoming reunion with Nicole. Nicole didn’t drink, and she was poetic, intelligent and sensitive.

I knew what not to do, but I didn’t have any idea what I should do.

Years before when I was an inexperienced basketball player, being watched made me self-conscious. I felt even worse if a beautiful girl was watching—I was both proud and nervous when I saw Nicole in the stands our freshman year in high school. My attitude changed completely as I acquired prowess on the court: by the time I was the highest scorer on the Varsity basketball team I drew extra energy from big crowds, and the more good-looking women in the stands the better I liked it.

Now I was a beginner again, only the game wasn’t physical. It wasn’t even sexual at this stage. It was psychological and emotional, and there would be no practice before game time. I required social skills to interact with an intelligent, sensitive woman like Nicole—and I didn’t have them yet.

I was reminded one morning that semester about the subtlety and insight required to deal with discerning women. I was sitting in an English literature class next to Lamartine McGavock, whom I’d met when we were freshmen honors students together in the Thematic Option. Marty was an athletic blonde from Laguna Beach and a member of Kappa Alpha Theta, the “rich girls” sorority. She’d grown up in Laguna when it was still semi-rural. There were still orange groves in Orange County when I returned from Germany in 1978, and Marty had grown up riding a horse in a corral on her family’s Laguna Beach property.

We hadn’t seen each other for about a year. Marty had been one of the most intelligent students in Thematic Option, and one of the very best looking. Her appearance was so gracefully polished no imperfection caught and held one’s gaze, and one’s eye seemed to slip right off the fine bones of her face and the taut athletic curves of her figure. Even our freshman year she’d dated upper classmen and now she was dating guys who had already graduated and were working.

Our class met on Tuesdays and Thursdays. When I asked Marty why she hadn’t taken a course by the same professor, whom we both knew and admired, the year before as I did, Marty shrugged and said, “It met on Mondays, Wednesdays and Fridays, and Friday classes don’t fit my lifestyle.”

One Thursday morning Marty arrived just before class started and collapsed into the seat next to me. “I’m so hung over,” she whispered to me. After class, Marty stayed in her seat as the other students got up and began to filter out of the classroom, a reflective expression on her face.

“Are you ok?” I asked.

She looked at me bleakly. “You know, sometimes it’s a funny thing being a blonde. Guys assume you’re stupid, and once they get drunk they reveal who they really are because they assume won’t understand.”

A chill ran down my spine as I looked into Marty’s intelligent, disillusioned, icy blue eyes.

“Their mistake,” I said.

“Yeah,” she said.

Any guy who thought sex, drugs and rock and roll—or looks, money and possessions—was the key to Marty’s or Nicole’s heart was a fool. But what was the key?

Neither Marty nor Nicole dazzled me with their looks and poise into being oblivious to my predicament. They were as intelligent and sensitive as I was, and they were beautiful women accustomed to assessing men by the criteria of the secret world.

Marty had clearly had similar experiences with at least some men. I assumed Nicole was having them too with at least some of the preppies at Amherst and now Williams. So at stake was something far more important than embarrassment, I wanted to make sure I didn’t give Nicole the mistaken impression I had forgotten who she was as a human being.

The Women’s Movement and the End of Romance

As if the ignorance of being virgin wasn’t awkward enough, I had a more basic issue: my family upbringing taught me that women considered sex disgusting. My mother grew up as a fatherless refugee girl in post-war Germany, and those experiences left her with deep resentment against men, whom she spoke of, at best, with ironic amusement and more frequently with mockery and contempt.

When I was boy, my mother continuously shamed and humiliated me for inhabiting a male body, treating me as dirty, ridiculous and disgusting. I believed her until high school, when years in locker rooms with my team mates introduced me to normal attitudes towards masculinity. I learned to be grateful for my masculine body and to appreciate its many capabilities, but locker room talk did nothing to discredit my belief that women thought sex and men were disgusting. What did it matter what my teenage team mates thought about girls and sex? What mattered was what teenage girls thought about us!

As a high school freshman, I began spending afternoons after school in the Command Reference Library located on the big US military base in the middle of Seoul. In search of understanding and guidance, I plundered its excellent resources, reading dozens of feminist interviews, articles and books, trying to understand how women felt about men.

At fourteen I read Betty Friedan’s The Feminine Mystique, in which Friedan declared the feminine mystique “fulfills itself only through sexual passivity [and] acceptance of male domination.” (Page 81).

Betty Friedan at home in the 1960s

Courtesy: Wikicommons

Yes! agreed Germaine Greer in The Female Eunuch, which I also encountered at the age of fourteen. “Female sexuality has been masked and deformed,” Greer wrote, explaining, “What happens is that the female is considered as a sexual object for the use and appreciation of other sexual beings, men. Her sexuality is both denied and misrepresented by being identified as passivity.” (Page 17) Greer blamed the notion of masculine-feminine polarity for “the castration of women” (Page 18) and declared it was responsible for “reducing all heterosexual contact to a sado-masochistic pattern” (Page 18).

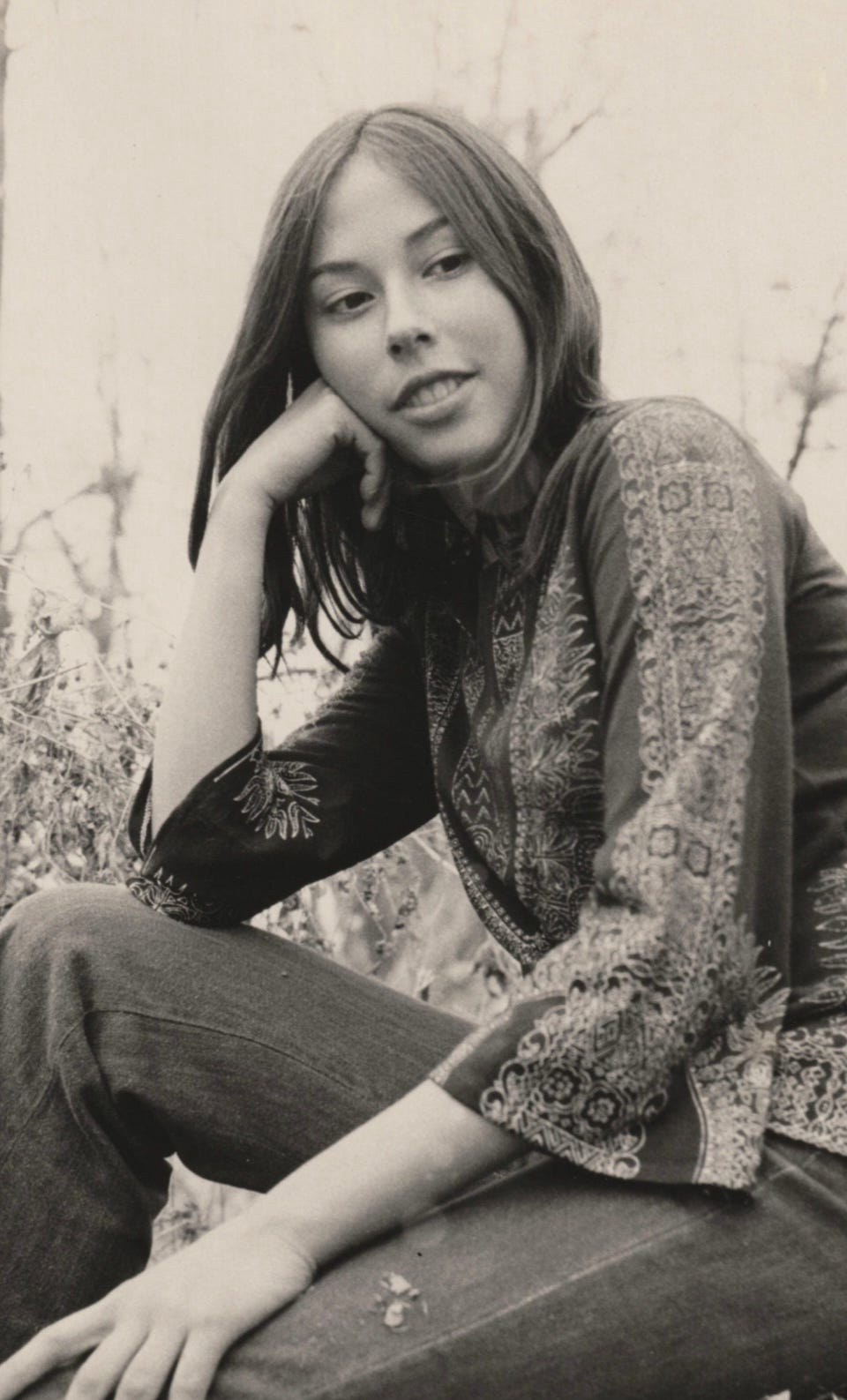

Germaine Greer in the 1970s

Courtesy: Estate of Keith Morris / Redferns

What I read was horrifying. I was in love with Nicole. Could the natural fulfillment of my love lead to such a creepy, distressing and demeaning experience? Apparently, yes, according to Friedan, Greer, and my mother. “Because love has been so perverted,” Greer insisted, “it has in many cases come to involve a measure of hatred. In extreme cases it takes the form of loathing and disgust.” (Page 19).

That sounded exactly like what I had heard at home. My mother disagreed with feminists about their policies on abortion, divorce, and life-long working careers for women, but they all shared a deep contempt for men.

Germaine Greer often sounded just like my mother. She had studied at the University of Sydney, where she was remembered long afterwards for her ability to “confidently, easily and amusingly put men down".

She and my mother said very similar things: “A full bosom is actually a millstone around a woman’s neck: it endears her to the men who want to make their mammet of her, but she is never allowed to think that their popping eyes actually see her . . . . [big breasts] are not parts of a person but lures slung around her neck.” (GG Page 40).

I didn’t need to be told this by Germaine Greer. My mother’s own striking figure automatically conferred upon her great power over the many men who instinctively stared at her breasts, an unconscious reaction my mother observed with satisfaction and contempt. She gloried in her ability to make men pliant to her wishes while reserving to herself lofty moral superiority over them.

Nicole was a beautiful introvert with an unconcealably voluptuous figure—but as my mother’s son I wasn’t (completely) distracted by Nicole’s gorgeous appearance: I knew who she really was. In one of her letters from Smith College, Nicole inadvertently described herself in terms very similar to how I had thought of her since we were thirteen: “Times like this make me wish I was born a plant, a fern who just lives, without having to have a goal, friends, parents, things. Without having to wonder why he’s alive. I wonder if people can ever accept the fact that they are alive just because. And for no other reason.”

Nicole the beautiful introvert

Twenty years later, I would write a novel Crisis Deluxe in which I looked back on my younger self and reflected on my feelings about Nicole when we were both teenagers:

“[She] . . . had been a beautiful girl, but she was also cold and reserved, the perfect first love for a boy who wasn't eager to turn into a man. I had always thought of Jacqueline as possessed of the beauty of a graceful tree, or an ocean wave, rather than something bred of flesh and blood. She had seemed to me like some highly refined mineral, or like the most elegant plant in a garden.”

The question for me was, what mixture of beliefs and values had Nicole developed in college? After all, she had studied, like Betty Friedan, at Smith College. The evidence was mixed. On the first page of Nicole’s first letter to me when we were freshmen, she wrote:

“Impressions of Smith: GIRLS, GIRLS & GIRLS!!

The few boys around keep their heads lowered with proper humility. Actually I think they are plain scared.” (12 September 1978)

In Nicole’s next letter in November, she seemed to have adopted a feminist perspective in one passage: “I have a pessimistic view of marriage—it seems that after living together so long a couple would get bored. What keeps most marriages together anyhow? Children. Chris—I’m serious I can’t have kids. I would rather kill myself. Something’s wrong with me—that I feel so strongly about this.” A few paragraphs later she wrote about Smith, “I was thinking of transferring before, because to be totally honest, the lack of men really bothered me, I thought it was unnatural. It still does feel strange at times, but I like the feeling of independence it gives me. That we don’t need to have men around, that the whole school is dedicated to teaching us & that we are intelligent in our own right.”

As her letters arrived for the first two years, Nicole showed signs of the very “crisis in women’s identity to which Friedan attributed her own radicalization when she herself was at Smith College.

A few weeks before the end of her freshman year, Nicole announced she was going to focus on becoming a biology major. She acknowledged she wasn’t sure what to do with her life, and asked, “Why not be a science major if you have that problem? I suppose a lot of my feelings stems from the resentment I feel when my parents & family (who are very music – art oriented people) try to channel me into that direction.

“Chris – do you think its wrong or arrogant to want to be good, very good, at what you do. I guess I mean, wanting to be good even when people tell you that you’ll not make it, that the road to it is too difficult for you.” (April 29, 1979)

Friedan described a similar dilemma. “I remember the stillness of a spring afternoon on the Smith campus in 1942,” Friedan wrote, “when I came to a frightening dead end in my own vision of the future. A few days earlier, I had received a notice that I had won a graduate fellowship. During the congratulations, underneath my excitement, I felt a strange uneasiness; there was a question that I did not want to think about. “Is this really what I want to be?” (Page 67)

At the time, Nicole questioned the invitation to the world of equal employment being offered to women of our generation: “I know you are very ambitious . . .Of all people I know, you seem to be one who’ll make plans to – I’m not sure how to say it – be happy in the future, I guess. By going into the Peace Corps, then law school you’ll experience & do your part for the world in general & at the same time be satisfied with yourself. Which is what life is a chase for, in a way. There must be another way of going through life besides being pulled through it kicking and screaming. Do I sound depressed? I’m not—just thoughtful. It’s times like this when just thinking about the future & past is sort of painful. Bittersweet.”

Betty Friedan remembered suffering mental torment as well: “I thought I was going to be a psychologist. But if I wasn’t sure, what did I want to be? I felt the future closing in—and I could not see myself in it at all. I had no image of myself, stretching beyond college . . . . Is this really what I want to be?” The decision now truly terrified me. I lived in a terror of indecision for days, unable to think of anything else. . . . . But still the question haunted me. I could sense no purpose in my life, I could find no peace, until I finally faced it and worked out my own answer. I discovered, talking to Smith seniors in 1959, that the question is no less terrifying to girls today.” (Page 68)

Or, for that matter, in 1979.

Nicole kept thinking about dropping out and taking a year off, and her feelings about Smith persisted and so she transferred to Williams College in 1980.

Most importantly, what did Nicole think about men and sex? I didn’t really know. When we were together in Seoul as freshmen in high school, Nicole had been friendly and welcomed spending lots of time together. As trust between us grew, she became shyly affectionate—but always very proper. Her parents would have been proud.

But was Nicole being a reserved, well-brought up young lady back then—or were Friedan, Greer and my mother right, and Nicole secretly felt disgusted about the prospect of sex? After two years at Smith College, the fact Nicole had chosen to transfer to Williams was encouraging—despite the intense competition it meant as I returned to USC three thousand miles away.

On balance, Nicole’s true feelings, based on what she had said and written to me in letters—even though she was now sleeping with men—could be interpreted either way.

The Secret World

Fortunately, that summer I had read Tropic of Cancer. The ignorance that had descended on me because of my indoctrination was annihilated by the blinding light of truth. Miller depicted a secret world that my mother and feminism declared did not, and should not, exist—and yet Henry Miller described in unforgettable prose proving beyond doubt that it did! In Tropic of Cancer Miller revealed a secret world I had never imagined.

It was a wonderful private world where a man and a woman desire each other and make their own intimate rules shaped by their mutual attraction. Kiss by kiss, caress by caress, their private rules evolve in mutual passion and are totally different from the official rules prevailing in the social, public world.

The women’s movement had declared “the personal is political”—instead of what Henry Miller—and the entire literary tradition of Western civilization—knew to be true, that in the secret world our true desires are revealed in secret intimacy between man and woman, and we express ourselves and fulfill needs—emotional, psychological, and physical—much deeper than politics and ideology.

According to Friedan, a traditionally feminine woman was “a passive, empty mirror, a frilly useless decoration, a mindless animal, a thing to be disposed of by others, incapable of a voice in her own existence.“ (Page 81), but this was how the narrator of Tropic of Cancer describes an encounter in a Parisian night club with a blonde with agate-colored eyes:

“I’m in her arms now and she has hold of me and I don’t care who comes or what happens. We wriggle into the cabinet and there I stand her up, slap up against the wall, and I try to get it into her but it won’t work and so we sit down on the seat and try it that way but it won’t work either. No matter how we try it it won’t work. And all the while she’s got hold of my prick, she’s clutching it like a lifesaver, but it’s no use, we’re too hot, too eager. The music is still playing and so we waltz out of the cabinet into the vestibule again and as we’re dancing there in the shithouse I come all over her beautiful gown and she’s sore as hell about it.” (Page 18)

In Tropic of Cancer Miller’s women characters reveled in their personal agency and were erotically attracted to the men who desired them. According to Greer that couldn’t be true: “All the vulgar linguistic emphasis is placed upon the poking element; fucking, screwing, rooting, shagging are all acts performed upon the passive female.” (Page 49)

The blonde with the agate-coloured eyes was no “passive female”. The narrator then describes a reunion with his wife Nora in which sex doesn’t disgust her at all (this is only a brief excerpt):

“I feel her body close to mine—all mine now—and I stop to rub my hands over the warm velvet. Everything around us is crumbling, crumbling and the warm body under the warm velvet is aching for me . . . . She lies down on the bed with her clothes on. Once, twice, three times, four times… I’m afraid she’ll go mad . . . “ (Page 19)

Tropic of Cancer depicts a world incandescent with the intense passion—sexual, emotional and psychological—men and women can feel for each other. Its depictions annihilated what my mother implied about her sex life with my father, and discredited Friedan pronouncements about “the empty, purposeless, uncreative, even sexually joyless lives that most American housewives lead.” (Page 244).

As a young boy, my parents had explained to me the mechanics of sex. But I had been completely misled about the emotional and psychological aspects of sex. For example, when I saw a pregnant woman I understood anatomically how she had become pregnant. But I assumed there was no real difference in her public demeanor and the way she’d behaved while conceiving her baby. I imagined she had been calm and composed, patiently enduring her husband’s masculine lust, and when it was all over she had pulled down her dress, patted her hair back into place, and gotten on with her life—just as I and everybody else, saw her now.

The idea that a woman could be like the blonde with the agate-colored eyes, nearly frantic with frustrated lust, or like Nora, close to going mad from waves of intense sexual pleasure—was a total revelation to me. That’s not what I had been told!

Oh no, wrote Friedan, the goal of the women’s movement was “a passionate repudiation of the degrading realities of woman’s life, the helpless subservience behind the gentle decorum that made women objects of such thinly veiled contempt to men that they even felt contempt for themselves.” (Page 90)

Tropic of Cancer revealed the enchanting sexual agency of women, hidden behind a wall of deliberate lies and the calm, socially prescribed demeanor men and women resume in public situations. Tropic of Cancer also showed that far from being passive, bewildered subjects forced to endure disgusting sexual acts, women knew how to get what they wanted.

Now that I knew sex with me wasn’t inevitably going to be a distressing “sado-masochistic” ordeal for Nicole, in which she would “passively” and with “helpless subservience” submit to a “sexually joyless” act of subjugation while filled with “hatred . . . loathing and disgust” I was liberated from my moral quandary. Now that I understood that only some women felt the way Betty Friedan and Germaine Greer reported, I was even more aware, virgin that I still was, that beneath the seemingly objective policy demands of the women’s movement for abortion, equality of employment, and sexual freedom, the real goal of leading feminists was to deny the erotic connection between men and women.

I’d been lied to. If Henry Miller was right, it meant my mother, Betty, Germaine, Gloria, Kate Millett and the rest were either part of a group of women who were incapable of enjoying sex with men—or, that they did enjoy sex, but for their own reasons chose to deny it. Their motivations didn’t matter—that was their problem. It was no longer my problem.

My challenge was to follow Nicole into the secret world of intimacy. The opportunity to accompany her on an equal footing, as would have happened in the context of nuptials, as two innocents learning from one another how to share intimacy, was lost irrevocably.

It wasn’t primarily a physical challenge, although facial expressions and body language would be more important than our already well-established communication through spoken and written words. To journey toward intimacy and self-revelation with such an intelligent, sophisticated and now (somewhat) experienced young woman, I would have to adeptly navigate psychological and emotional paths as I progressively manifested my deepest feelings by incarnating them with Nicole.

What mix of friendly and hostile beliefs lurked in Nicole’s consciousness? What combinations of affection and resentment, of attraction and antagonism? What desires and aversions defined her libido? What scores did she yearn to settle with her lovers for emotional wounds inflicted by her upbringing or by initial sexual experiences with men—and how would she express them sexually?

I would have to sleep with Nicole to find out.

Los Angeles - City of Lost Angels

Living in Southern California gave me a small, and much-needed, edge to maintain my slipping position on the status hierarchy with the Alpha males surrounding Nicole at Williams.

Three thousand miles away, I did my best to play the weak hand I had been dealt, and one of my strongest cards was my life in Southern California. Throughout our sophomore year and the summer before our junior year, I filled my letters to Nicole with accounts of social events, and eating and drinking in the coolest restaurants and bars in West LA and Beverly Hills, surrounded by actors and movie industry power brokers. A couple nights a week my friends and I went to Café Figaro, the Polo Lounge, Moustache Café, Le Dôme, the Whiskey a Go Go, the Comedy Club, Rainbow Bar, and many others and I wrote about those evenings to a studious Nicole hitting the books in cold, rural, western Massachusetts.

ID 343243860 © Ruzica Stojcetovic | Dreamstime.com

I had an advantage in LA I didn’t have yet in the secret world. In LA, I was a semi-insider: many of my friends and fraternity brothers at USC came from current or future Hollywood dynasties. Like the secret world itself, the barrier to entry into the coolest places in Los Angeles wasn’t money: even the meager cash I earned working twenty hours a week as a bi-lingual teacher’s aide at an elementary school was enough for me to afford the LA bars, bistros and restaurants pulsing with Hollywood and rock n’ roll glamor. The real barrier to entering this glamorous world was relationships. You had to know people, and those people had to decide you were to be included. What happened next was up to you.

The atmosphere of Southern California was sex-saturated in the 70s and 80s. LA was a sunny enclave still protected from the cold, blighting winds of the feminist gale beginning to wilt American culture. Every time I drove the LA freeways and listened to the radio I was reminded of Henry Miller’s secret world. Gloria Steinem was popularizing the declaration that a woman needs a man like a fish needs a bicycle, but Los Angeles hit radio stations KLOS and KMET constantly played Patti Smith’s great song, released the year before, “Because the Night”:

Take me now, baby, here as I am

Pull me close, try and understand . . .

Love is an angel disguised as lust

Here in our bed until the morning comes

Come on now try and understand

The way I feel under your command.

Patti Smith didn’t attend Smith College—much less Columbia, where Kate Millett’s PhD thesis had become the manifesto for the women’s movement Sexual Politics.

In Southern California, this period was the last great flowering of Hollywood. The anthems of Los Angeles were “Hotel California” and “Life in the Fast Lane”, which warned about the intimate compromises required to access the glittery world of fame and fortune. Southern California was full of men and women who were celebrated in those songs as “Eager for action / And hot for the game”.

All human culture and civilization arises, directly or indirectly, from the sexual union between men and women. Sex between a man and a woman generates creative energy in an endless variety of ways beginning with the creation of new life itself.

The Hollywood of that era still celebrated the sexual desire between men and women. The Industry, as it is still called in LA, nourished a sprawling, creative and dissolute community always welcoming to youth, beauty and some kind of talent (with a flexible definition of talent). Sex and adventure were both the greatest subjects of the movie and music businesses and the energy that powered the machinery. The Industry offered ambitious, attractive young people a choice: climb the sheer, slippery mountain face hand-hold by hand-hold, or pay the toll on the highway up the slopes. It was understood you were expected to give head to get ahead.

Even those of us on the periphery of the Industry felt the sexual energy pulsing through the film and music communities. The law firm where I had worked as a summer intern was the most powerful entertainment law firm in Los Angeles, but it was part of the official, proper business world. The young associate lawyers there jokingly told me, “We touch the papers that touch the stars”. It wasn’t where the juice was.

When I drove to my job at Wyman, Bautzer I listened to Michael Franks’ LA jazz songs, including “Eggplant”, “Down in Brazil” and “Popsicle Toes”. Their sly, erudite, erotic lyrics hinted at the way LA really worked. Michael Franks was one of Hollywood “It Girl” Eve Babitz’s countless lovers. She claimed credit for the phrase “popsicle toes”, declaring it was her feet that were chronically icy, even in LA’s balmy climate:

“You got the nicest North America

This sailor ever saw,

I'd like to feel your warm Brazil

And touch your Panama.

But your Tierra del Fuegos

Are nearly always froze,

We gotta seesaw

‘Til we unthaw

Those popsicle toes.”

Her figure certainly matches the admiring description in Franks’ lyrics:

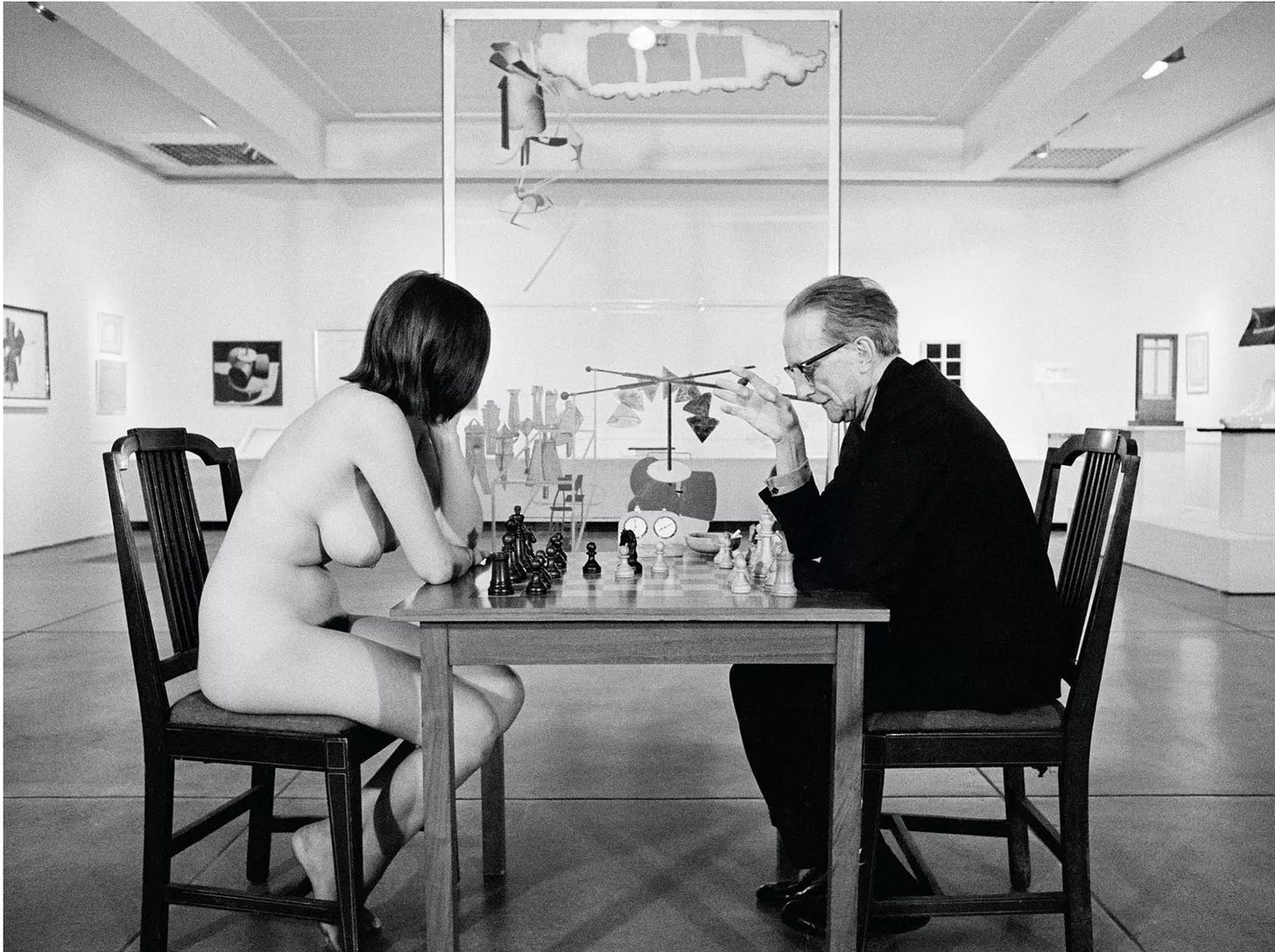

Eve Babitz playing chess with Marcel Duchamp

Pasadena Art Museum

In addition to her famous photo with Marcel Duchamp, Babitz was a talented designer of album covers and the author of the excellent LA memoir, “Slow Days, Fast Company.” But when Babitz badly burned herself years later in 1997, her mastery of the LA mixture of official and unofficial talents was revealed. Her countless Hollywood friends organized a star-studded benefit to raise money for her medical bills while she was still in the hospital. When somebody told her Steve Martin and Harrison Ford had each contributed $50,000 to the benefit, she whispered, “Blow jobs,” and collapsed back onto her pillow. (Hollywood’s Eve by Lili Anolik, page 193).

Things happened all the time in LA for mysterious reasons impossible to understand unless you recognized the town was saturated with sex. In fact, the entire history of Hollywood is incomprehensible without factoring in the invisible but all-pervasive energy of sex. Deals, movies, casting choices, executive promotions—even huge business mergers were catalyzed by sexual energy.

The thing is—it worked. The greatest movie studio of the era was Paramount Pictures. When Charlie Bluhdorn’s sprawling conglomerate Gulf & Western bought Paramount Pictures in 1966, Hollywood’s verdict was that the takeover was “the biggest purchase for pussy in the history of American business.” (Vanity Fair, April 2001, Robert Sam Anson) A rival movie mogul’s wife commented years later, “Bluhdorn bought Paramount to get laid. It was that simple.” (Vanity Fair April 1997, Nick Tosches). But the highly libidinous atmosphere of Paramount Pictures produced some of the greatest films ever made, including: The Godfather films, Chinatown, Love Story, Raiders of the Lost Ark, Saturday Night Fever, Rosemary’s Baby, and True Grit.

I’d studied Homer’s Odyssey my freshman year with Marty McGavock. By my junior year at USC I felt like I was Odysseus steering between the Scylla of feminism and the Charybdis of dissolute Southern California culture. Jack Nicholson’s daughter was my friend’s roommate. I sat at tables next to Robert Wagner and Zsa Zsa Gabor and countless other stars. Mary Tyler Moore’s son tragically killed himself two blocks from my apartment. I was being accepted into the LA ruling class, but I was feeling increasingly alienated.

Then I received news from Columbia University that I had been accepted for the Spring semester beginning in January.

I began preparing in earnest for New York. My mom and I drove to Beverly Hills to buy warm clothes for the New York winter. The men’s department at I. Magnin was a small boutique with carefully curated clothes. My mom and I were by ourselves as I tried on sweaters until the great actor James Mason arrived. There was not even a sales clerk, and the four of us drifted around each other for half an hour.

It was a classic LA situation. I had just seen James Mason in Stanley Kubrick’s film Lolita a few weeks before at a West Hollywood re-run theatre. Mason had been brilliant as the erudite pedophile Humbert Humbert, one of Nabokov’s most sinister characters. Mason tried on several bathrobes—the very costume he had worn in Lolita. I’d learned how easy it was to make casual conversation—and you never knew where things went from there. If I had been an ambitious young man, this might have been my chance. Or not. You never knew in LA.

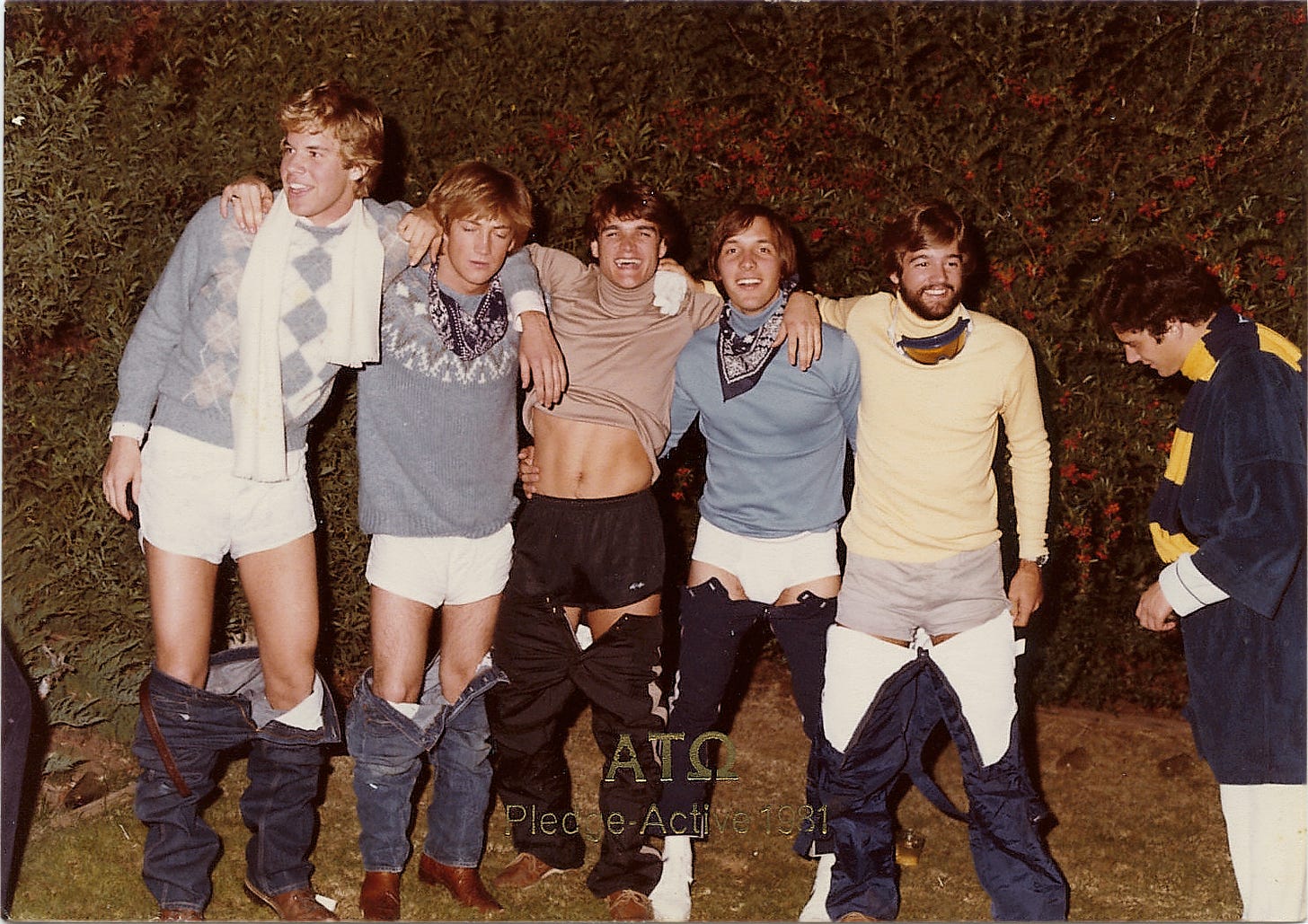

I stayed focused on Columbia and seeing Nicole again, and came away with what seemed like a perfect sweater for Columbia. I wore it to a ski-themed fraternity party a month before leaving for New York:

Only after I arrived at Columbia would I realize the sweater should have been black.

The God of my Father

My strategy of presenting Nicole with a glamorous Southern California version of myself precipitated a severe spiritual crisis. While everything I had written Nicole was all true, the emphasis was misplaced. For example, I really did spend 45 minutes in close proximity to James Mason at I. Magnin just after seeing him star in the film Lolita, but I cared far more about trying to understand Nabokov’s world view than I did about a celebrity sighting. The truth was, my deepest values and core interests had nothing to do with the glitzy Southern California lifestyle I was presenting to Nicole in my letters. I had gone much too far offering a sophisticated façade to compensate for being an inexperienced virgin.

One evening towards the end of the semester, I was sitting at my desk in my room at the fraternity house studying one evening. I had sent off a letter to Nicole earlier that day.

I suddenly felt myself in the presence of God. It was similar to what happened after my desperate appeal the night on Corfu. The palpable presence of a consciousness, to which I was completely transparent, regarded me through my own personal consciousness as if my mind were the lens of a microscope or telescope, and this consciousness was looking through my mind and seeing everything. I too could see my life with pellucid resolution. The sentences in the letter I’d just written Nicole rose before my eyes. I was appalled by the letter’s brittle, scintillating web of falsehoods. I saw my true self obscured beneath the sticky, sparkly filaments of lies and the soiled tissue of false Southern California values. What I wrote Nicole was true, but I had concealed my real feelings, and my true self was almost completely invisible beneath the artificial image rising from the pages.

I was filled with loathing for the fake façade I had presented in the letter, and I also loathed myself for writing the letter.

The earthly pole of this suddenly-revealed relationship with God, whose presence was palpable in my interior, transfixed me. His own consciousness remained invisible, obscured in darkness and silence at the celestial end of the pole, hovering far above where I sat at my desk. I was overcome by vertigo. Restless and distressed, I abandoned my homework and went to the fraternity bathroom to take a shower. It was past midnight during the week, and nobody else was in the bathroom. As I stood under the shower my altered state of consciousness continued, and I could see through the rising billows of steam swirling around me visions of recent scenes in my life. It was as if I were floating slowly past a river bank on which the scenes were playing out. I watched myself saying fake, superficial and pretentious words. Watching myself talk and act, I was filled with self-hatred and disgust. Finally, I became light-headed from the steam and emotional duress, and I turned off the shower. I went back to my room, where my roommate was sleeping blissfully through my crisis.

I dressed quietly and sat on the sofa.

My overwhelming spiritual crisis revealed a paradox to me: what I was experiencing was the palpable—and intolerable—consequences of allowing my soul to nearly die by adopting false values and devoting my energy to constructing a life of lies. I had not channeled my love for Nicole, a love which itself I had proven time and time again, into becoming my best self. Ironically, my yearning for authentic intimacy had motivated me into the assembly and construction of a false self. I had made a big mess. My soul craved freedom and mutual self-expression with a loved one. Instead I was willingly enslaving myself.

I prayed, as I did years before on the night at Corfu.

I told God I was giving up all responsibility for my life and wanted him to take control. I wanted that pure, objective, all-seeing consciousness to remain within me. I wanted this infinitely superior consciousness to descend from its obscurity and inaccessibility, to appear within me, and to discern from that moment onward the right path through the disconcertingly inexplicable thicket of choices and decisions that I was faced with by the enigmatic reality of life. I invited Jesus, as the living nexus of the divine and the human, to reside in my heart and guide me in all my decisions.

In the aftermath of this prayer, I felt sense of overwhelming relief. I also felt a rush of new freedom. I had rejected the false version of myself I had been constructing in order to get synchronized with social norms in Southern California and impress Nicole while masking my naiveté and ignorance. It seemed to me that I could discern the truths under the deceptive masks, distorted mirrors and other appearances on the surface of life.

It was around dawn. My cynical, sophisticated, mentally unstable roommate, the son of a wealthy Beverly Hills family, was still asleep, out of sight in his upper bunk.

I called my father, waking him, and in a whisper I explained to him what had happened that night. I was wrung out and a little tearful. He was surprised, groggy, and but as I explained myself using religious concept and words familiar to my father, he became encouraging. I could tell he was bewildered, even baffled, though. According to his religious beliefs, I had already become a Christian when I was about three years old, and I had been saved ever since. There was not room in his worldview for a metanoia at this stage of my life. Nevertheless, he welcomed the unexpected news and we hung up.

I could tell my roommate was now awake, but he lay silently in his bunk. Except for an oblique, sardonic joke he made later that day, neither of us ever referred to what I said that morning. There was a cosmic irony in my compulsion to call my father as the coda to the night of inner tumult. I’d grown up resenting the harshness of my father’s black and white rules, and chaffed under the injustice they so often produced, but I’d given him credit for living by them himself. That had changed over the past two years. I’d witnessed a series of incidents that discredited his beliefs and de-legitimized the integrity with which he lived them. My swerve into Southern California values had been an attempt to replace what I considered the dysfunctional rules my father had imposed on me with a more empirically sound set of rules.

My father’s God made his presence palpable, and displayed his power, by making successes happen. God loves you, I was taught, and He has a wonderful plan for your life.

But there was a catch: when apparent setbacks and defeats occurred, they were signs, according to my father, that I had allowed sins into my life which had created a barrier between myself and God: not being admitted to Harvard, for example. Such an event signaled abandonment by God because we had made ourselves unworthy through our sins.

Sometimes my father’s religious beliefs seemed to explain things: I’d resisted temptation and hadn’t slept with Kalina that night on Corfu, and within a month I had a totally unforeseen, amd seemingly miraculous, opportunity to drive Nicole and her father to San Francisco.

But what if the love of my soul had lost her virginity to another man? Was I being punished? Or was I meant to enforce some religious standard of purity and abandon my love for Nicole in order to preserve God’s love for me? By my late teens, I had seen and read too many examples of adversity appearing in the lives of good and great people not to suspect adversity itself was an avoidable part of the process by which makes a person better, and isn’t necessarily a sign of God’s disapproval, at all.

I had also witnessed my father’s own blighted career hopes, and my parent’s disintegrating marriage, personal defeats for him which exerted tremendous stress on his theodicy. Was he being punished for sins despite a lifetime of devout Christianity? In the past several years, I saw my father struggling to understand his own life, and he seemed increasingly bewildered.

The God of my father asserted himself that night. I learned that however limited and faulty my father’s perspective might or might not be, God was intensely, empirically real. Just as I had rejected the misleading veil behind which my mother had obscured the empirical reality of the secret world, I now accepted the empirical reality of Being behind the increasingly implausible doctrines of my father. So after this intense night in God’s presence it was natural for me to call and tell my father about my encounter with the God to whom he had introduced me.

The next day I wrote a chaser letter to Nicole apologizing for the letter I had just sent her. Nicole wrote back and told me she hadn’t seen anything wrong with the letter. Far from being reassured, I interpreted Nicole’s reply as more evidence she was becoming increasingly detached and indifferent to me; we were no longer intuitively connected despite having co-evolved in important was from early adolescence to early adulthood. I was confused and hurt.

I was in a state of anxious foreboding as the end of the semester approached at USC and my start at Columbia University loomed. I was more aware than ever of my failure to discern the entrée into the secret world. I would be showing up on the East Coast unprepared. I had no skills, and I didn’t know how the game was played.

What I did have was a model for the kind of emotionally astute and sexually accomplished man I wanted to be when Nicole and I entered the secret world together. The same year I read Betty Friedan and Germaine Greer, I’d read Frank Yerby’s novel The Dahomean. I had never forgotten the climactic scene. It happens on the wedding night of the Dahomean aristocrat Hwesu, who as a reward for his courage on the battlefield, is married to a daughter of the King of Dahomey. The catch is that the King’s numerous royal children are permitted to indulge in sexual behaviour which is totally taboo for the rest of the Dahomeans.

Hwesu’s bride Princess Taunyinatin has already acquired a long list of lovers, including her own brother. In a society which insists on a bride’s virginity, at the wedding Princess Taunyinatin wears the bridal gown of a virgin, while slyly mocking and insulting her new husband Hwesu in numerous ways during the ceremony. Princess Taunyinatin cleverly manipulated the ceremony into a humiliating series of subtle challenges to her bridegroom. On their first night together, Hwesu handles her contemptuous rebellion by engaging in expert and extremely prolonged foreplay until the experienced and cynical Taunyinatin is driven wild with sexual desire, and Hwesu then, in Yerby’s words, made intensely physical love to her with “a virility none of the soft and pampered princelings she had ever known before could ever dream of matching. (page 365)” Hwesu succeeds in sexually satisfying and utterly exhausting his royal bride.

The couple’s final, and ultimate, challenge is not being able to provide their families with the blood-stained sleeping mat that would testify to the bride’s virginity. As morning dawns, Hwesu stands up and cuts his arm, “Smiling at her, he let it pour down his arm and off his fingers until it made the same deep, dark, oval-shaped splotch that ruined virginity does, there on the sleeping mat, amid the semen stains.” (page 366). His royal bride is completely taken aback, “For either his gesture was the tenderest proof of love ever dreamed of, or a terrible mockery” but against all expectations she becomes a sincerely loving and completely faithful wife.

Hwesu’s epic performance on his wedding night was not only a fictional example of how an experienced lover might behave, it was a reminder of the difference between the fictional character and me. Hwesu is already married to three wives and has had numerous previous lovers by the time of his expert handling of the emotional, romantic, psychological, and sexual nuances of his fraught wedding night with Princess Taunyinatin.

Hwesu based his actions on a foundation of experience I totally lacked. The fictional scene was another reminder of standards that seemed dispiritingly beyond my grasp, as my father’s religious rules had been. And of course, behind rules purporting to explain reality, there really was an empirical reality. I’d have to develop my own rules.

Nicole was the love of my soul. What was most fundamentally at stake was not about having sex with Nicole for the first time. What I had learned since the summer removed any hesitation I felt caused by the misunderstanding that sex was inevitably distressing and repugnant to Nicole. It was clear now sex could be a positive rather than negative development for our relationship. But my dreams were not limited to sleeping with Nicole. I wanted to marry Nicole, to raise a family together, and to live together for the rest of our lives.

Whether or not Nicole even thought of her future in those terms was a big question, and the possibility of living a happily married life together was what was most fundamentally at stake as our reunion approached. In 1980, was a romantic ending even possible anymore?

Betty Friedan’s purpose for writing The Feminine Mystique was to convince young American women to reject what she called “The Mistaken Choice” (Page 212) of marrying, having children, and raising a family. She visited Smith College in 1959, the year before Nicole and I were born and was indignant that the majority of Smith College students “behaved as if college were an interval to be gotten through . . . so ‘real’ life could begin. And real life was when you married and lived in a suburban house with your husband and children.” (Page 175)

In The Feminine Mystique Friedan wrote with horror about a survey of Smith College graduates from 1957. Within three years of graduating, 97% of Smith College graduates were married, 89% were housewives, and only 3% would get divorced. Friedan noted disapprovingly:

“of 20 per cent who had been interested in another man since marriage, most ‘did nothing about it.’ 86% of the mothers planned their children’s births and enjoyed their pregnancies; 70% breastfed their babies from one to nine months. They had more children than their mothers (average: 2.94), but only 10 % had ever felt “martyred” as mothers. Through 99% reported that sex was only “one factor among many” in their lives, they neither felt “over and done with sexually”, nor were they just beginning to feel the sexual satisfaction of being a woman. Some 85% reported that sex ‘gets better with the years,’ but they also found it ‘less important than it used to be.’ They shared life with their husbands ‘as fully as one can with another human being.’ (Page 431)

Friedan also cited as further proof the terrible waste of the economic potential of American women that 125th anniversary survey of Mount Holyoke graduates in 1962, “showed a similar high marriage and low divorce rate (2%) . . . and the percentage having four or more children showed a dramatic rise.” (Page 435)

In The Feminine Mystique Friedan urged American women to escape “The comfortable concentration camp that American women have walked into, or been talked into by others” (Page 369) and spent an entire chapter drawing meretricious parallels between their suburban homes and Auschwitz.

Friedan wrote disapprovingly, “Never have so many women, with the freedom to choose, had so many children, willingly,” (Page 18) and cited as an urgent crisis the fact that “By the end of the fifties, the United States birthrate was overtaking India’s . . . . Statisticians were especially astounded at the fantastic increase in the number of babies among college women. Where once they had two children, now they had four, five, six.” (Page 3)

Betty Friedan sure fixed that!

Even though Friedan admitted in The Feminine Mystique that: “Early sex . . . has always been a characteristic of undeveloped civilizations, and in America, of rural and city slums,” (Page 330), the influence of women’s movement had convinced the majority of young women in Nicole’s and my generation to choose early sex for themselves.

In 1960, during the heart of the “crisis” Friedan was hell-bent on addressing, 61% of American women were virgins when they married. By 1980, only one in seven American women were virgins when they married.

Towards the end of the semester, I was feeling discouraged and defensive. I wrote Nicole, lowering expectations for our reunion, predicting we wouldn’t get along, and telling Nicole we would probably be disappointed when met. I pointed out we didn’t know each other anymore, throwing doubt on the value and meaning of our five and a half years of correspondence and phone calls. My forecast was neither proleptic nor prophetic—but what I wrote to Nicole at the end of 1980, and how she chose to respond, would change our lives.

On the day I left for New York in the first week of January, 1981 the weather was still balmy in Southern California. It was drizzly and foggy in the mornings but by afternoon the temperature in LA was in the mid-70s Fahrenheit. The morning I landed in New York City, the sky was bright robin’s egg blue. The temperature was a 17 degrees Fahrenheit. That night it would drop to 4 degrees Fahrenheit. The meteorological reading was just the first many challenges I would be facing on the East Coast.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS: Special thanks and deep gratitude for the awesome editing suggestions and insights of

Really this. I like the weaving of sex with thinking about writers on sex…You get the dishonesty of the feminists and the honesty of Eve Babitz. Amazing how Eve and her sister Mirandi grew up with their parents' ex-pat artist friends including Eve's godfather, Stravinsky.

Your essay "The Secret World DE9" offers a compelling exploration of the hidden dimensions that shape our reality. By delving into the unseen forces and underlying structures that influence our perceptions, you invite readers to question the nature of truth and the boundaries of their understanding. Your thoughtful analysis encourages a deeper contemplation of the complexities that lie beneath the surface of everyday life. Thank you for sharing such an insightful and thought-provoking piece.