Spirit as Energy

Before revealing the secrets of the spiritual journey of St. Teresa of Avila, it’s important to address the widespread, false, modern belief that spirituality has no physical reality in the real world.

Many people assume that synonyms for “spirit” include “intangible”, “unmeasurable”, “undetectable”, and “metaphysical” rather than physical. A standard assumption of our time is that when “spirit” and “spirituality” is being discussed, we are no longer talking about an issue that is empirical, evidence-based, and data-driven.

That’s a false assumption.

For the past fourteen years, I’ve daily practiced Tai Chi for an hour a day, and it’s interesting to me how often Teresa’s description of the sensations she feels, which she describes with great directness and clarity in her Autobiography and her masterpiece The Interior Castle, resemble the various ways that chi energy manifests when cultivated and directed with the ancient techniques of Tai Chi.

I will provide one concrete example from my Tai Chi experiences that resembles the descriptions Teresa provides about her spiritual experiences. I was doing push hands with a member of my Tai Chi family: he had his arms crossed across at chest height with his hands gripping his elbows, and I was pushing on his forearms with my hands trying to force him to take a step backwards. We were practicing trying to release a particular kind of force expressed by chi energy when the correct technique is applied.

I was using bio-mechanical force–in other words my muscular strength–to push hard on him, but the point of this exercise was for him to apply Tai Chi principles, not resist my muscular force, and return my chi energy to me (one of our Tai Chi brothers was standing videoing this with his phone from about ten feet behind me; I’m wearing white and my push hands partner is wearing blue):

Source: Author’s Collection

He had been trying for some minutes to release this energy, but all he was doing was pushing back on me with his own muscular strength, unable to get the Tai Chi technique exactly right. All we were doing was engaging in a disjointed shoving match of clashing joints and contracting muscles. The two Tai Chi masters in charge of this course came over and made some adjustments to his arms, gave him a few technical hints, and stepped back.

Suddenly, he got it.

The energy appeared out of nowhere. Instantly, I felt overwhelmed by a huge flood of water from an invisible waterfall moving so fast I was completely uprooted from where I stood, swept backwards off my feet, and dumped upside down over the waterfall.

I had no time to react. The energy surrounded me like thundering water, from nothing to overwhelming force and tossed my 210 lb body through the air like a chip of wood.

Although you can see he’s touching my elbow with one hand and seeming to wrench his forearm out of my grip with his other arm, I had no sensation of being touched in any particular place. I felt simply buoyed up by this overwhelming rush of water, turned upside down and thrown to the floor. And what was uncanny, spooky, was that it appeared from nowhere with maximum force.

It wasn’t like stepping on the accelerator of a Mercedes or a Porsche, in which—although it’s abrupt—you feel the difference between the start and full throttle, or even a Tesla, which accelerates even more quickly. The wave of energy went from being completely off to totally on: there was no torque curve, no rising pressure gradient: one moment I was pushing on my partner, and in the next split second I was flying down and backwards--gone.

So powerful was the energy enveloping me that in a second I was on the floor, my feet in the air, skidding on my back for about ten feet until I knocked down the person videoing us like a bowling pin and he fell on top of me:

You might ask what martial arts has to do with spirituality . . .

I’m glad you asked.

EXTERNAL AND INTERNAL MARTIAL ARTS

There are two domains of martial arts: external and internal. Most people know only about external martial arts like boxing, Brazilian Jiu Jitsu, Krav Maga, and Tae Kwon Do. These martial arts rely on the physical qualities of speed, strength, quickness, and specialized holds and grips. They are violent and destructive disciplines which generally leave both opponents beaten up and often badly injured, as anyone can see by watching even a brief excerpt of a UFC match.

External martial arts have no connection with spirituality except that suffering, pain, fear and defeat are all opportunities to test our characters, shed our faults, and acquire virtues that are rarely learned without enduring suffering. In addition, external martial arts for the most part violate, or tempt their practitioners to violate, the greatest spiritual teachings and moral codes of all ancient cultures.

Internal martial arts are typically transmitted in carefully guarded lineages. Internal martial arts players cultivate the flow and application of energy: conventional bio-mechanical principles have nothing to do with internal martial arts. Internal martial arts are deeply related to the greatest spiritual practices, and Tai Chi lineages monitor and test their practitioners for their ethical development as well as the technical expertise. The ultimate internal martial art is Tai Chi, which is also the highest and greatest martial art of all. Tai Chi also incorporates moral principles that are consistent with the teachings of the great religions, including the commandment of Jesus not to resist your enemies.

MARTIAL ARTS, MINDFULNESS, AND COGNITIVE NEUROLOGY

Internal martial arts are, in fact, a particular application of mindfulness. The foundation of all mindfulness is a prolonged, repetitive, series of practices that are initially deeply boring. Anyone who has tried meditation is vividly aware of how incredibly tedious, physically uncomfortable, mentally annoying, and physically grueling those first few sessions can be. Our Western minds, particularly since the IPhone era, are wired in a completely different way, which is interesting, because hidden in the achievements of Western civilization are countless hints of mindfulness practices that have fallen into general disuse and been largely forgotten, except for isolated and specialized groups.

I wrote that our brains are “wired” deliberately to refer to the billions of synapses in the neurological system of every human being, which originate in the brain but radiate out through our entire bodies. Most people think that once childhood is over our brains lose their ability to change significantly. In fact, in the last two decades cognitive neuroscience has established that adults can dramatically reconfigure the way the neurons in our brains fire. These new patterns of neurological functioning enable us to achieve entirely new levels of high performance, or to regain functions lost after physical injuries.

In a previous series "A Mystery Hidden in Plain Sight" I discussed four individuals, most of whom I know personally, who have achieved remarkable results, including becoming the fastest man in the world, by applying these ancient techniques in order to rewire the neurons in their brains. The techniques are very basic and accessible to anybody with patience: the basic practice is to develop the ability to focus sustained mental attention, often by repeating a short group of words, either mentally or orally, and another ancient technique is to focus mental attention by carefully observing one’s own breathing.

The reason breathing is so fundamental to mindfulness is because our breath regulates the vagus nerve, which in turn is responsible for regulating critical body functions such as heart rate, blood pressure, breathing, digestion, and our immune systems. The influence of the vagus nerve on our parasympathetic nervous system gives it the key role in the hormones flowing through our bodies, and therefore our moods and states of mind—which we Westerners typically think of as purely mental phenomena.

Courtesy: Joe Martino

The Stanford scientist Kelly McGonigal describes the connection between performance enhancements and the physiological changes to the human brain created by mindfulness techniques:

Neuroscientists have discovered that when you ask the brain to meditate, it gets better not just at meditating, but also at a wide range of self-control skills, including attention, focus, stress management, impulse control and self-awareness. People who meditate regularly aren’t just better at these things. Over time, their brains become finely tuned willpower machines. Regular meditators have more grey matter in the prefrontal cortex, as well as regions of the brain that support self-awareness.

— Maximum Willpower: How to master the new science of self-control by Kelly McGonigal

https://a.co/7k2GlQ3

The initial changes are mental, but our transformed brain evolves new ways to optimize our physical capabilities, often beyond what we could have imagined. My friend Mike Agostini became an Olympic athlete and the fastest man in the world by stumbling across these techniques as a boy on the island of Trinidad and Tobago.

When we think of improving our strength, speed, coordination and other physical capabilities we focus on our muscles, cartilage, sinews and connective tissue—but it is our brain that is instructing our body to perform. It is first our brain we need to reconfigure by training networks of neurons, synapses, axons and somas to fire in new combinations, instructing our body to function in new ways.

One of the clues to the nature of Teresa’s spirituality is how long she had to persevere before her remarkable spiritual experiences began, because it is persistent effort over many months and years that transforms our brains. This is a hint that Teresa stumbled onto the power of mindfulness.

MINDFULNESS AND ENERGY

Many of the remarkable powers conferred by mindfulness can be understood as the result of brain plasticity, changes to wiring of our neurological system, and control over the vagus nerve.

But mindfulness practices influence another fundamental physical layer of our neurological system, because neurons emit electricity. Our brain generates an electrical field, and every thought and action we have is reified by an electrical charge in our body. Our hearts generate an electrical field that extends for a diameter of approximately a meter around our bodies.

Courtesy: Joe Martino

It’s an empirical fact that our bodies generate electricity and that electricity is fundamental to the operation of our brains and hearts. How it does so is a mystery. Maxwell’s equations established that all forms of energy are related along a single continuum: light, heat, electricity, radiation, magnetism, and so on.

In my Tai Chi group we have numerous PhDs, including STEM PhDs, and we’re all learning to use chi energy. My guess is that chi must be a kind of energy somewhere on Maxwell’s electromagnetic spectrum. Just like the average person has no idea what electricity is, but knows how to walk into a room and flip a switch to turn the lights on, we are learning Tai Chi techniques without being able to understand why they work.

Chi energy is naturally generated by humans, horses, and other animals. Tai Chi techniques that amplify and direct the force expressed by chi, the physical results are just as physically dramatic as the lamprey eel’s ability to generate a significant amount of electricity.

The connection between Tai Chi and spirituality is that Tai Chi principles are based on the same principles and techniques that were first discovered in the Indus River Valley civilization of ancient India, and applied to meditation and spiritual enlightenment. The difference is simply the application of these principles and techniques. Broadly speaking, in India these principles were applied to yoga, pranayama, and other meditative techniques for achieving advanced states of consciousness, while in China these principles were applied to martial arts, including Tai Chi using the unarmed hands (“empty fist”), sword fighting, spear fighting, archery, and horse riding.

Am I claiming Teresa discovered Tai Chi? No, but I am claiming that Teresa independently discovered ancient energy techniques and applied them for her own purposes.

ST. TERESA’S WRITINGS AND TAI CHI

You may wonder why I compare St. Teresa’s spiritual discoveries to Tai Chi, instead of to mindfulness applications that seem to be more closely related, such as meditation.

Firstly, there are clear parallels between mindfulness meditation and some aspects of St. Teresa’s spirituality. The rosary was already in use in St. Teresa’s day, and there are many similarities between the practice of Roman Catholics who repeat short prayers and keep track of the sequence with their rosary, and the meditative practices of Hindus and Buddhists who keep track with their malas of how many times they’ve repeated their mantras. Depending on how the prayers are recited, they can easily regulate the breath and therefore influence the vagus nerve in ways that generate calm and serenity.

But St. Teresa, although known for her remarkable calm in stressful circumstances, achieved more spectacular effects than calm and serenity. Her spiritual states were certainly very physical, as Bernini emphasized in his famous statue, discussed more fully in Part One:

My friend Harriet, who has devoted years to serious meditation and is now in India on a personal pilgrimage, reminded me of the way St. Teresa’s protégé St. John of the Cross loved Christmas Mass and would become so absorbed in union with God he was completely unaware of his surroundings. Harriet pointed out how John’s state of consciousness (and Teresa reported that she experienced the same states) is paralleled by the great Hindu saints who regularly entered samadhi.

What’s fascinating is that Teresa was a writer of genius, and once she broke through, after fourteen fruitless years, to being what she called a true “contemplative” she left us very clear descriptions of her states of consciousness which seem to indicate she had learned to cultivate and apply energy.

Let’s consider one of Teresa’s most famous spiritual descriptions, the image of the four stages of prayer as a personal mental garden each of us tends, and which we keep watered by one of four methods. In her schema, a beginner’s prayer life is like watering a garden by laboriously drawing a bucket of water up from a well; in the second stage of prayer, a hand crank or windlass makes the chore of obtaining water for the garden easier; in the third stage of prayer an irrigation system waters the garden with very little effort; by the fourth stage in a person’s prayer life a fountain wells up from an inexhaustible spring in the center of the garden, and without any human will abundantly waters a flourishing garden of prayer. What exactly is this water in Teresa’s description of a person’s prayer practice?

The literature of Tai Chi is filled with very ancient and pervasive comparisons of chi to water. As I described above, when my partner succeeded in unleashing the chi energy on me, I had a strong sensation of water, of being swept helplessly over waterfall. My first sensations of energy after months of daily practice, was the feeling in my hands of wearing medical gloves filled with warm water. Without delving into the almost infinite technical details of Tai Chi methodologies, the importance of water as analogy for energy in the Tai Chi tradition is epitomized by this classic and justly famous quote from that Tao Te Ching: “Nothing is softer or more yielding than water, yet nothing on earth can resist water.”

Tai Chi also expands one’s mental awareness of the world. One of my earliest experiences of push hands illustrates this. I was too early in my Tai Chi journey to direct any spectacular expressions of energy, but nevertheless the energy flowing between my push hands partner and I as we both focused on sensing one another’s personal “energy statement” produced a surprising moment when I suddenly felt his leg as if it were my own, and a split second before he stepped back I had the physical sensation that his foot was already planted on the floor behind him—before he actually moved. I felt it as tangibly as if it were one of my own legs—in effect my third leg appeared in that instant.

Remarkable as this may be (and it is a typical Tai Chi experience), it has a scientific basis in the fact that neurological research has established that a split second before we ourselves become aware of one of our own thoughts, the electrical pulses from our synapses fire in our brain—before we are consciously aware of the thought.

Tai Chi seems to plugs us into other energy fields (including those of horses, for example) and allows our minds to track the electrical pulse of another person’s synapses—and correctly interpret the meaning of the energy. Horses have the ability to sense their rider’s intention as well; many high level equestrians report being able to command their horses with their thoughts alone.

So perhaps it’s not surprising that St. Teresa compares progressively enlightened mental states with water: it seems to indicate that, however she understood her own experiences of exalted consciousness, they were produced by energy-based conditions.

ENERGY AND EUROPEAN ART

It is widely but incorrectly assumed that the mindfulness techniques developed in the Indus River Valley never reached the West. But for thousands of years there have been extensive relationships between the Mediterranean and the Near East through India as far as China, and recent scholarship is continuously multiplying new examples. In fact, recent scholarship makes it clear that mindfulness techniques could have reached Greece and Rome easily from India directly, or even from China.

Courtesy: UNESCO

The exchange of ideas, goods, and populations between the cultures connected by these trading and invasion are too numerous to describe, but I’ll just mention a couple. The Classical Greeks called the Chinese “Seres” and the Romans tried vainly to legislate against wearing silk, because Romans were mad for the fabric and it was more precious than gold in Rome. Alexander the Great and his army battled all the way to the banks of the Indus River and fought Indian armies reinforced with elephants. This is a statue from the Gandara region of India, which was settled in 327 BC by Greeks, expressing classical Greek aesthetics in the life-like human body and the representation of the drapery:

Source: TheCollector.com

Alexander the Great slept with a copy of Homer’s Iliad and a dagger under his pillow, and scholars believe that the Homeric epics The Odyssey and The Iliad may have inspired the great Sanskrit epic The Mahabharata, the core of which is the sacred text The Bhagavad Gita. Isn’t it likely that the great civilizations of India and China would have transmitted their precious ideas to the West? As a matter of fact, there is plenty of evidence for this influence.

PRAYER IN THE GREEK AND RUSSIAN ORTHODOX TRADITIONS

One still-living mindfulness tradition in the West originated in the breathing techniques adopted by the Greek Desert Fathers, who applied pranayama to the new religion of Christianity. These ascetics applied the Biblical instruction to “pray without ceasing” by mapping to each inhale and exhale a short repetitive “Jesus Prayer”. They lived in caves or in some famous cases on stylites:

By Unknown author - https://meyer-schodder.jimdo.com/festegedenktage/simeonstylites-27-07/, Public Domain, https://commons.wikimedia.org/w/index.php?curid=96273864

These prayer-based breathing techniques have been practiced for almost two thousand years in the Greek Orthodox Church, and when Russia was Christianized by Greek missionaries over a thousand years ago, those breathing techniques were adopted along with the Greek prayers by the Russian Orthodox Church. Today, these very breathing techniques are fundamental to the extremely intense Russian martial art known as Systema.

Source: Jennifer Osborne, Slate Magazine

I have practiced Systema, which combines external techniques with internal techniques anchored in breathing. In some ways Systema resembles Brazilian Jiu Jitsu. It is so rough and violent that, after starting Systema in my late 50s, I decided there was just too much violent contact to be participating in at my age. Even though I know from personal experience how quickly Systema breathing techniques allow one to recover from extremely hard strikes, I decided the possibility of injury was just too high.

TAI CHI AND WESTERN ART

The typical experience of an uninitiated spectator when looking at genuine Tai Chi videos or performances is that it’s somehow being faked. Seeing people fly backwards, or pulled helplessly forward, doesn’t make sense. We don’t know what we’re looking at.

There’s a strong possibility that the same confusion may be true when we look at Greek and Renaissance sculpture and art. To explain I’ll have to briefly describe at a high-level the key Tai Chi techniques. They’re what I perform every day for an hour during my Tai Chi form practice.

Although Tai Chi is a purely energy-based martial art, it does teach physical techniques. My push hands partner wasn’t able to unleash energy on me until he got those physical nuances perfect.

The most fundamental physical discipline in Tai Chi is to maintain a clear distinction between the areas of the body that are expressing Yin and Yang.

Try to think of this symbol not as static but as a moving wheel with the black and white swirls constantly morphing into one another and then back again.

The Taoist philosophy on which Tai Chi is based teaches that Yin is the primordial feminine principle and Yang is primordial masculine principle. The two polarities are deeply connected and evolve into one another. In Taoist thought, the entire universe came into being, and evolves continuously from past to present to future, through the dance of Yin and Yang. Yin evolves into Yang, Yang evolves into Yin.

In Tai Chi combat, the weighted part of the body is Yin, and the “empty” or unweighted part of the body is Yang. A Tai Chi player’s movements generate a continual flow through the body between Yin and Yang, as first one leg and the opposite arm are the Yin limbs, and then as the player transfers his weight from the Yin leg to the weightless Yang leg, the now-“empty” Yin leg becomes Yang and the previously weightless Yang leg becomes the “full” Yin leg bearing all the player’s weight. The continual switching between the pure polarities of Yin and Yang concentrates the chi energy and allows it to flow through the player’s body.

Courtesy: Andrew B. Watt

In the sketches above, the Yin limbs are indicated in black, and the movement of the chi energy around the player’s body is shown in gold. The great Tai Chi fault is to place equal weight on both legs. This is called the fault of “double-weighting” and makes the energy stagnate and stop flowing. Both legs bear equal weight only for an instant, in the transition from Yin to Yang or Yang to Ying.

This flow allows the body to generate energy. The circular movements of Tai Chi and the alternating polarities resemble the physics of generating electricity. Electricity is generated by spinning a magnet. The whirling magnet’s positive and negative charges follow a circular path, succeeding each other and generating the flow of electricity. Similarly, a Tai Chi player’s body continuously alternates between the pure polarities of Yin and Yang to generate chi energy.

TAI CHI AND CLASSICAL AND RENAISSANCE ART

Classical Greek sculpture repeatedly portrays the exact moment when Yin becomes Yang. The statue below is an ancient reproduction of a marble original by Praxiteles in the 4th Century BC, and it shows the figure stepping forward and unweighting his back foot (Yin to Yang) and putting his weight on his front foot (Yang to Yin):

There are numerous examples but I’ll provide just one more iconic sculpture by Praxiteles, the Persephone of Knidos, an ancient Greek town significantly located on the land mass of Asia Minor, where it would have been more accessible to influences from the East than Greece itself. Significantly, Homer was a native of either Asia Minor or the island of Chios just off the coast of Asia Minor, and the greatest Pre-Socratic philosopher Heraclitus, whose thought has a distinct “Eastern” sensibility, was a native of Ephesus, a famous Greek colony located on Asia Minor:

Again, the back leg has just changed from Yang to Yin and the front leg has just become the Yin leg.

It seems possible that art historians (who are unlikely to be high level martial artists, although there may be a few) haven’t fully understood what they’ve been looking at, and merely ascribed these characteristics postures to aesthetics and the Classical Greek notions of elegance. The possibility that energy techniques were integral to what these statues expressed to their contemporary public is consistent with the sacred purpose for which these statues were originally sculpted, and their location in temples. We can safely assume that every detail matters in an image created by a great artist, and although we can’t be sure, is it likely to be a coincidence that this precise moment was depicted in a sacramental image?

During the Renaissance, sculptors sought to match and then surpass the achievements of the Classical Greek and Roman sculptors. Not surprisingly, the clear distinction between Yin and Yang recurs. I’ll just offer two examples among multitudes, the “David” of Michelangelo and the “Perseus” of Cellini. In Michelangelo’s great sculpture, all David’s weight is on his right leg, which is the Yin leg, and in fact it’s easy to imagine he’s just about to launch a hip strike with his “empty” Yang left leg. To delve into a deeper level of Tai Chi technique, the vertical access of the sculpture originates in David’s right “Yin” foot, skirts the inside of his knee (a Tai Chi energy “gate”), transects his groin and importantly the area between the groin and navel where chi is stored in the body, and then rises along what’s called the microcosmic orbit of David’s spine and the front of his abdomen and chest, up through the neck, palate and the crown of his head. This is the path along which chi energy circulates in the human body:

In the gory and dramatic image below, Perseus has just been squatting on the crumpled body of Medusa and, her severed head raised high, is now about to step off her body, having unweighted his left leg, which is now Yang:

How much of the lore of the East was retained in the Renaissance? Were Renaissance sculptors simply blindly imitating Classical models without understanding any more than modern art historians do what was being portrayed? It’s impossible to say.

But it’s certainly interesting that Renaissance art prominently uses Greek iconography showing Jesus Christ, saints and other holy figures using hand gestures that are the same as Tai Chi hand gestures. This is the famous painting of Jesus Christ as the Saviour of the World by Titian, who painted this during Teresa’s lifetime:

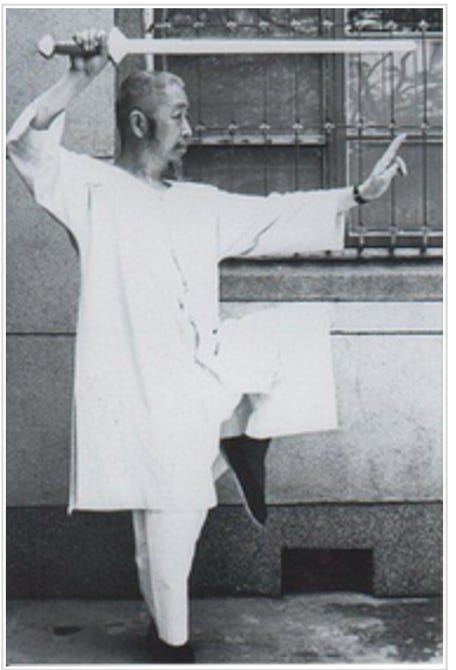

By comparison, have a look at the Tai Chi gesture used by the great Cheng Man Ching, who brought Tai Chi to New York City in the late 1960s, and founded one of the most widespread Tai Chi lineages in America:

The gestures the risen Jesus Christ is making in Raphael’s “Transfiguration”, painted just before Teresa’s birth, are also the same as a typical Tai Chi gesture as demonstrated again by Cheng Man Ching:

Again, it could be argued these hand gestures are either meaningless, or that their correspondence to Tai Chi energy gestures is coincidence. But it seems unlikely that ancient Greek iconography dating from almost two thousand years ago, at a time when there was major interaction between the Mediterranean and both India and China, would incorporate into sacred imagery the exact hand gestures used to release energy—and have absolutely nothing to do with these Eastern traditions.

There are many clues in every corner of the European tradition to the existence of a now-forgotten European awareness of energy techniques. For example, the closest friend of St. Francis of Assisi was St. Clare, another wealthy child of a prominent family who abandoned everything to follow the example of St. Francis. St. Clare’s father Count Favorino Scifi had reconciled himself to the loss of a highly marriageable daughter who could have been used to bolster his family dynasty by a strategic match, but when his younger daughter Agnes decided to follow her sister’s example Count Scifi drew the line: he dispatched his brother and a team of armed men to retrieve Agnes.

By António de Oliveira Bernardes - GONÇALVES, Susana Cavaleiro Ferreira Nobre (2013). Universidade de Lisboa, Faculdade de Letras, Public Domain, https://commons.wikimedia.org/w/index.php?curid=6146937

Accounts vary slightly, but as the men dragged off Agnes she became so heavy they couldn’t lift her body any longer and dropped her. Her uncle Monaldo’s arm went numb and then he suffered sudden paralysis in the limb. The heaviness, numbness and paralysis are characteristic expressions of chi energy. These events occurred in the early 13th century, three centuries before Teresa was born.

We are inclined to ascribe the credulity of 13th century Italians who believed this really happened to their ignorance and primitive belief in miracles. We should consider the possibility, however, that Europeans understood what we no longer understand when we look at the same sculptures and paintings, that energy techniques were real and produced dramatic effects.

TAI CHI AND EROS

We associate the word “erotic” with sexuality and sexually arousing phenomena. The one benefit of this conceptual grounding is that we understand the erotic as a deeply physical condition, one that involuntarily motivates us and needs to be channeled in order to be expressed in a socially appropriate and ethical manner.

Our intuitive understanding of the erotic is a good way to understand chi energy. A novice in Tai Chi must endure many months of tedious, repetitive form practice, and learn to simultaneously (begin to) relax while staying alert. Once progress has been made, the first stirrings of sensation appear in the body of the Tai Chi practitioner, what the Tai Chi tradition calls “feelings.” Energy feels good, a slightly pleasant warmth in a very, subtle, delicate and tender way---like the memory of an orgasm. These feelings become stronger as a practitioner learns to mobilize energy, providing a guide that make daily practice both physically enjoyable and intellectually intriguing.

Plato’s notion of eros, which pervaded the consciousness of Classical Greeks, was of a powerful force that fills an individual in a very physical way and yet motivates them to great deeds out of a strong attraction to another person. The core example in Plato’s Dialogue Symposium (which means “Dinner Party”) is the heroic woman Alcestis who willingly gave her life for her husband Admetus, even though Admetus had many relatives who should have offered themselves before Alcestis did, because Alcestis “surpassed her in-laws so far with her philia on account of her eros.” Philia, often translated as “brotherly love”, is the force that produces strong bonds between individuals, while eros is a mysterious life force that is catalyzed by desire in one individual for another individual and motivates the lover to the greatest deeds.

Eros is fundamentally a causal agent in the world. Yes, many of these extraordinary exploits are sexual, but by and large they are much more expansive and have important social, political, economic and military significance. What is the connection between the Classical Greek concept of eros and energy? We will take a close look in the discussion of the poetry of Teresa’s protégé St. John of the Cross, because his poems remarkably map in a very precise way the erotic topography of the Symposium.

As I bring this essay to a close, I’d like to suggest you reconsider the assumption that spirituality is a state of goodness. It’s as false as the idea that spirituality is not physical. The Greeks understood eros is morally neutral. It’s also easy for us to understand how erotic motivation might produce the sexual exploitation of another human being, and the Greeks were careful to distinguish between the neutral power of eros and the deed itself. Classical Greeks understood that eros could motivate extraordinary exploits that were shameful, such as becoming rich or committing treason, and it could motivate extraordinary exploits that were noble, such as self-sacrifice, heroism in battle for one’s city, the creation of beauty.

Similarly, energy is neutral and its applications can benefit or destroy humanity. Spirituality is like a chessboard with a set of white pieces and black pieces on which good and evil forces endlessly contend with one another. One of the great Tai Chi players of the 20th century was an exceptionally cruel and ruthless Chinese collaborator with the bloodthirsty and racist Japanese Imperial regime. Many of the most senior Japanese Army officers were deeply observant Zen Buddhists. Of the two greatest samurai sword fighting manuals, The Book of Five Rings was written by a homicidal maniac and the other, The Life Giving Sword, was written by his martial equal who refrained from killing and chose to defeat opponents without bloodshed. Whatever you may think about his politics, Ho Chi Minh was an advanced Tai Chi player.

As we study Teresa’s spirituality we will see abundant evidence of the seeming paradox that physical feelings can generate both exceptional real-world consequences and powerful moral deeds. These are the works of energy.

How could this possibly fit within a Roman Catholic context? As a matter of fact, energy, which is the life force also known as chi, is at the very core of foundational Christian claims about the nature of human beings and our physical reality. For almost two thousand years, hundreds of millions of Christians have said, “I believe “Et in Spiritum Sanctum, Dominum et vivificantem “(And in the Holy Spirit, Lord and Giver of Life).”

For more than a thousand years, they probably understood its meaning better than we do today. We will discuss in the next post how Teresa re-discovered for herself the real meaning of the Nicene Creed.

It's so generous of you to devote your time and energy to producing essays like this Chris. It's a breath of fresh air to be taken deep into a consideration and nourished with such a depth of perspective. The fundamental point that sticks with me, and which I have come to see is true for myself, is that we don't know what we are looking at. The world is not what it seems. There are truths, mysteries, miracles, treasures, and wonders right under out noses that we can't detect due to the equipment failure most of experience in the modern-day west. We really don't know much about how to operate the psycho-physical human apparatus beyond the bare minimum. Wisdom practices, such as Tai Chi, that begin to awaken our capacity for the subtle and energetic perception and capacity you describe are being lost. It's vital that we get reminders like this—look deeper, look again, wait, feel, question, inquire. I'm quite delighted that you're setting the stage this way for the next installment of Theresa I've been waiting for.

I loved how you tied art, history, science, and tai chi so elegantly in one post. This is awesome, Chris!

That last part about distinguishing between "the neutral power of eros and the deed itself" really speaks to me. It reminds me of all the tools (and energies) we have at our disposal - how it's all neutral, but it takes a person of great character to use them in constructive ways.

I've actually been thinking about learning tai chi for some time. I just hadn't found the motivation. But this post took my fascination of tai chi to another level. I have to start taking some classes!