Photo 7982585 © Cardiae | Dreamstime.com

I first read Henry Miller’s novel Tropic of Cancer when I was nineteen years old. It was the summer of 1980 and Henry Miller had just died at the age of eighty-eight in nearby Pacific Palisades. When I read the news, I drove to Book Soup on Sunset Boulevard in West Hollywood and bought his sexually explicit masterpiece Tropic of Cancer. I was still a virgin.

The bottom of the first page electrified me:

“I have no money, no resources, no hopes. I am the happiest man alive.”

I was stunned. Was it actually possible, I wondered, to have no money, no resources, and no hopes—and be the happiest man alive?

All my money, and a large portion of my family’s resources, were committed to funding my college education. My father had a plan for my life and I had agreed to it: I was in college on the West Coast, so I would crush the LSAT and win a spot at the best law school on the East Coast, obviously Harvard. My career as a lawyer would be brief, because it would merely set the stage for getting elected to the U.S. Congress. As a Congressman, I would position myself to become a United States Senator, and my accomplishments as a Senator would prepare me to run for election as President of the United States.

In other words, I had the highest and longest term hopes I could possibly imagine. I just had to follow the plan.

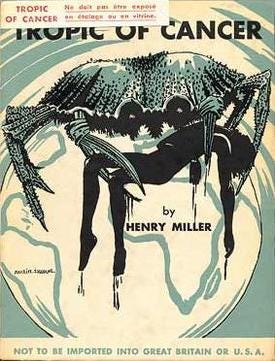

The cover of the 1934 first edition of Tropic of Cancer.

By the time I opened Tropic of Cancer that summer, though, I already realized I had a big problem. I was working between semesters as a gofer at the top entertainment law firm in Los Angeles. It was my first experience with the legal profession.

Hollywood Power, old and new: Creative Artist Agency’s global headquarters in the foreground, with the Century Plaza Towers in the background.

The firm occupied three floors in one of the Century Plaza Towers in Century City, the business district of Beverly Hills. The client roster was packed with world-famous Hollywood stars and West Coast rock stars, not to mention icons like Diana Ross. The firm was a gateway to status, money and power: top partners were located in corner offices with incredible 180 degree views of Beverly Hills and Hollywood, and lesser partners worked next to them in smaller offices with stingier views. One of those lawyers was made a new partner that summer. He chose not to move his office, instead he signaled his new status by having his office walls covered, at enormous expense, in gray flannel.

I hated everything about that law firm.

I saw from below how the machine worked: the partners could dispatch me to drive their daughter around Beverly Hills for two days of shopping while her Porsche was repaired but the ordinary lawyers couldn’t ask me to get them paper clips from the supply closet. The secretaries of the top partners bossed around the secretaries of the other partners—and treated the secretaries of rank and file lawyers like servants. I despised the hierarchy and those who believed it actually expressed something real.

So the first page of Tropic of Cancer was like a bomb going off underneath my father’s plan for my future.

The opening sentences of Tropic of Cancer had won my trust immediately: “I am living in the Villa Borghese. There is not a crumb of dirt anywhere, nor a misplaced chair. We are all here and we are dead.”

I was not surprised Henry Miller stated he and everyone else was dead. My father had given me key context for interpreting the statement years before when I was still a boy. One day he asked me, “If the penalty for eating the fruit from the Tree of the Knowledge of Good and Evil is death, why didn’t Eve and Adam die when they ate it?

I thought about it. It was a good question, and because I believed the Bible was true, I wanted to know the answer.

“I don’t know,” I said.

“Because it was their souls that died,” my father said. “We don’t feel any sensation when our souls die. We don’t know our souls are dead until we die physically and stand before God at the Last Judgment.”

I got it.

Walking around with a dead soul apparently doesn’t feel any different. We pay the price, however, after our physical death, when we discover to our horror our souls are doomed to suffer for eternity in Hell.

I respected Henry for announcing the consequences of what he was about to write about, up front. Furthermore, on Page 99 Henry seemed to confirm my father’s teaching: “I have found God but he is insufficient. I am only spiritually dead. Physically I am alive. Morally I am free.”

In the next paragraph, Henry reveals that despite the cleanliness and order of their living quarters, his housemate Boris is lice-ridden and needs his assistance:

“Last night Boris discovered that he was lousy. I had to shave his armpits and even then the itching did not stop. How can one get lousy in a beautiful place like this? But no matter. We might never have known each other so intimately, Boris and I, had it not been for the lice.”

I had already experienced the deep sense of acceptance that comes with nakedly revealing ourselves to others as our honest, embodied selves. Growing up with my brother and sister, and my years on the high school varsity basketball team with my teammates helped me understand that revealing my naked body created a shared bond with another human.

My varsity team mates and I didn’t shave each other’s armpits but we spent hundreds of hours together in the locker room completely naked. This was before the Gay Revolution and our intimacy had nothing to do with sex—in fact our matter-of-fact openness would have been impossible if sex was a possibility between us. There was nothing physical about ourselves the entire team didn’t know—starting with how long our dicks were. Our conversations were just as open, although limited by our ignorance about most things worth talking about.

Tropic of Cancer was no James Bond novel. I’d read them all in my early teens. Even in my inexperience, I recognized them as propaganda for what was then called “the Playboy lifestyle”, not realistic guides for becoming a man. It was clear to me that Ian Fleming’s fables about beautiful spies and counter-spies in implausibly glamorous settings around the world, having sex and killing their opponents and one another, were unrealistic. For starters, none of the characters—especially not James Bond—gave any thought to the eternal consequences of their actions.

By contrast, Henry Miller had addressed that very issue frankly in the first paragraph of Tropic of Cancer. Even if it was bad news, he was honest about it. I felt I could trust him to reveal the good and the bad about sex just as honestly.

For me, as it was for so many young men in those long-ago days before the Internet and its ocean of pornography, sex with a woman was an adult secret kept carefully hidden from us. Shakespeare, one of the few writers greater than Henry Miller, has Hamlet describe death as “the undiscovered country from whose bourne no traveler returns,” and at that time sex was almost as remote and hidden an essential human experience as death.

What little information leaked out was fundamentally contradictory, like the Indian parable about the ten blind men who each describe a part of the elephant they are touching, assuming in their ignorance the part represents the entire elephant. Despite the stereotypes, guys said very little in the locker room about their experiences with their girlfriends. Sex might as well have been death in every practical sense, because all the travelers I knew who had in fact returned from that undiscovered country said almost nothing.

I’ll never forget reading this passage on Page 17 of Tropic of Cancer for the first time:

“In that Paris of ‘28 only one night stands out in my memory—the night before sailing for America. A rare night, with Borowski slightly pickled and a little disgusted with me because I’m dancing with every slut in the place. But we’re leaving in the morning! That’s what I tell every cunt I grab hold of—leaving in the morning! That’s what I’m telling the blonde with agate-colored eyes. And while I’m telling her she takes my hand and squeezes it between her legs. In the lavatory I stand before the bowl with a tremendous erection; it seems light and heavy at the same time, like a piece of lead with wings on it. And while I’m standing there like that two cunts sail in—Americans. I greet them cordially, prick in hand. They give me a wink and pass on. In the vestibule, as I’m buttoning my fly, I notice one of them waiting for her friend to come out of the can. The music is still playing and maybe Mona’ll be coming to fetch me, or Borowski with his gold-knobbed cane, but I’m in her arms now and she has hold of me and I don’t care who comes or what happens. We wriggle into the cabinet and there I stand her up, slap up against the wall, and I try to get it into her but it won’t work and so we sit down on the seat and try it that way but it won’t work either. No matter how we try it it won’t work. And all the while she’s got hold of my prick, she’s clutching it like a lifesaver, but it’s no use, we’re too hot, too eager. The music is still playing and so we waltz out of the cabinet into the vestibule again and as we’re dancing there in the shithouse I come all over her beautiful gown and she’s sore as hell about it.”

What Henry Miller wrote contradicted everything I had been told growing up.

Coming all over a woman’s beautiful gown? I was astounded—and not by the sex. It was the friendly behavior of the women that amazed me, and their agency. The blonde had placed Henry’s hand between her legs and held his prick like a lifesaver as they danced in the bathroom. The American women were unflustered by his erection and merely winked as they passed by.

“I stumble back to the table and there’s Borowski with his ruddy face and Mona with her disapproving eye . . . when we get back to the hotel I vomit all over the place, in the bed, in the washbowl, over the suits and gowns and the galoshes and canes.”

Henry could not have been more dirty, disgusting, and outrageous. But the women didn’t exile him, or call the cops, at the first hint of misconduct. The blonde didn’t get “sore” at Henry until he ruined her dress (after failing to enter her, which probably contributed to her exasperation). As the next passage would reveal, Mona would forgive him for both his straying and his vomiting.

The blonde with agate-colored eyes, and Mona (in the next passage) were attracted to him—not spiritually, or just emotionally—but physically—and not despite, but because, he was a man (although a crazy one). The sexual attraction of the women to Henry seemed to include a maternal attitude which led them to indulge and forgive his reckless, bad-boy, behavior.

Could it be possible that women actually liked men? Was it possible that sex could actually be playful and fun?

It was like a second bomb going off.

I had been raised to believe the exact opposite.

By the time I was nineteen and reading Tropic of Cancer, I had accepted long ago my mother’s teaching that women considered men contemptible and their bodies dirty, smelly and ridiculous. Women were beautiful and clean—men were disgusting and dirty. Women were emotional, subtle and moral—men were unfeeling, crude, exploiters with only one thing on their minds.

While I was still in high school I’d read Betty Friedan’s The Feminine Mystique, Germaine Greer’s The Female Eunuch, and Susan Brownmiller’s Against Our Will: Men, Women and Rape. Gloria Steinem was everywhere in the media of the late 70s and early 80s. I would soon read Simone de Beauvoir’s The Second Sex. So I knew exactly what second-wave feminists thought of men: they all agreed with my mother.

Nineteen years old - convinced I was unattractive and disgusting to women

Our family dog was female because female dogs were cleaner than male dogs, or so we were told. My penis was dirty because I didn’t wipe it after peeing the way girls wiped themselves (as a boy, I tried and realized it was pointless). My mother quoted like Gospel something one of my aunts said, men would stick their penises into anything, even a piece of wood with a hole drilled in it.

The way we are treated by our parents as infants during the practical aspects of our earliest upbringing generate hormones that make us feel, even as babies, we are loved, cherished and precious—or unlovable, afraid, worthless, and ashamed. Long before our conscious memories begin, we feel the positive hormones of oxytocin, dopamine and serotonin—or the negative hormones of adrenaline and cortisol, when we are being breast-fed (or not), having our diapers changed gently and lovingly (or not), and while being hugged and kissed (or not).

One of the reasons I was so attentive to Henry Miller’s frank emphasis in Tropic of Cancer on dirt, lice and squalor was because my mother deployed cleanliness—and its opposite, dirt—as a powerful vector of shame and guilt.

As Henry Miller did, my family too lived in Paris for a couple years when I was a young boy. My mother took this photo after she caught me playing with the coal scuttle in the basement of our house:

I have no memory of my earliest years, but I think you can see in my eyes and expression the deep remorse and guilt I had been taught to feel, not to mention fear of punishment. So I was amazed by Henry Miller’s audacity, but even more by how tolerant and forgiving women could be.

That was not my experience.

By contrast with what happened to me when I accidentally smeared coal dust on myself that Parisian day in 1964, Henry’s escapades in Paris one night in 1928 had almost no consequences. In the very next chapter, he writes about his reunion with Mona a few months later, when Henry is received by Mona with unquenched ardor:

“Strolling past the Dôme a little later suddenly I see a pale, heavy face and burning eyes—and the little velvet suit that I always adore because under the soft velvet there were always her warm breasts, the marble legs, cool, firm, muscular. She rises up out of a sea of faces and embraces me, embraces me passionately . . . . she talks—a flood of talk . . . . I hear not a word because she is beautiful and I love her and now I am happy and willing to die. We walk down the Rue du Château . . . . Everything soft and enchanting as we walk over the bridge. Smoke coming up between our legs . . . I feel her body close to mine—all mine now—and I stop to rub my hands over the warm velvet . . . . and the warm body under the warm velvet is aching for me.”

Mona has forgiven Henry for everything that happened when she left Paris, and they return to the same room where he’d vomited all over:

“Back in the very same room . . . The trunk is open and her things are lying around everywhere just as before. She lies down on the bed with her clothes on. Once, twice, three times, four times… I’m afraid she’ll go mad… in bed, under the blankets, how good to feel her body again! . . . . And now it is a heavy bedroom, breathing regularly . . . sap still oozing from between her legs, a warm feline odor and her hair in my mouth. My eyes are closed. We breathe warmly into each other’s mouth . . . . To have her here in bed with me, breathing on me, her hair in my mouth—I count that something of a miracle. Nothing can happen now till morning. …” (Pages 19 – 20).

I had never imagined that anything like the friendly intimacy and companionship between Henry and Mona was possible between men and women. And their friendship and ardor didn’t cease when they were naked—it intensified! I’d been raised to believe women intensely disliked sex, and that the basic reason women resented men was because men forced sex on women. But Mona didn’t resent Henry at all, even when the dirt and squalor re-appear:

“I wake from a deep slumber to look at her. A pale light is trickling in. I look at her beautiful wild hair. I feel something crawling down my neck. I look at her again, closely. Her hair is alive. I pull back the sheet—more of them. They are swarming over the pillow. It is a little after daybreak. We pack hurriedly and sneak out of the hotel. The cafés are still closed. We walk, and as we walk we scratch ourselves.” (Page 20)

Henry and Mona flee the bedbugs, sneaking out of the hotel in the early morning and the chapter ends on a hopeful note as they find another hotel, and make a seemingly successful appeal to Mona’s lover in New York to send money: “By morning something will happen. At least we’re going to bed together. No more bedbugs now. The rainy season has commenced. The sheets are immaculate . . . “

It wasn’t Henry’s descriptions of sexual pleasure that got my attention—it was the way he described the friendly companionship between men and women, their mutual physical attraction, and the way sex brought them closer together and made them happier. Henry depicted being valued, desired, and wanted by a woman, despite what he had done.

Reading Tropic of Cancer made it possible for me to hope I too might someday be loved and desired by a woman for who I really was—not the suffocated, castrated, repressed, constrained version of myself that society seemed to require. I’d been taught to be on my best behavior, to try to be minimally acceptable, to not offend—and I was sick of it.

But it would take me most of the next year to figure out what to do about it.

Special thanks for wonderful editing and insights from Nicole Lee and Joyce Flinn

This was so good, Chris. And TOC is one of my favorite pieces of modern literature, by a genius author.

Your dissection of Tropic of Cancer cuts through the usual shock-value discourse to reveal the raw vulnerability beneath Miller’s provocation. The way you frame its ‘virginal’ quality—that collision of awe and revulsion toward existence—resonates deeply. A rare take that honors the work’s literary merit without sanitizing its chaos.